It may seem strange to start with an obituary, but this is the way I first came across Helen, when I was filling in the background to our Irish holiday, April 2025. For Helen’s childhood on Valentia, please see “Irish Odyssey Day 6, Part 2: Valentia Island”.

“Miss Helen Blackburn, whose death is reported, acted as secretary (and afterwards honorary secretary) for many years of the central committee for women’s suffrage in London having been at an earlier period secretary of the Bristol and West of England Suffrage Society. For a number of years she edited The Englishwoman’s Review, a quarterly publication recording the course of various women’s activities at home, in the Colonies, and abroad.

“The deceased was born in Ireland and spent her early youth at Valentia where her father managed some slate quarries for the Knight of Kerry. Her father possessed gifts as an inventor and was driving about Regent’s Park in a horseless carriage of his own construction more than twenty years before the appearance of the modern motor car.” (Horfield & Bishopston Record & Montpelier Free Press, 17 January 1903.)

Helen’s sudden appearance and the unexpected link between her birthplace, Valentia Island, (in the rugged southwestern corner of Kerry), and Bristol, was enough to blow me off my chair.

The Irish “Valentia” is not to be confused with the Spanish “Valencia”, though it is often spelt the same way, especially in old documents and newspapers. But first, there is no credence in the moonshine I was told (as a wide-eyed ingenue, young and romantic), that the name came from the tongues of rescued Spanish Armada sailors. Pre-enlightenment communities on all remote rocky coasts of the British Isles expected to make a supplementary income from the bounty of shipwrecks, (hence the initial strong opposition to lighthouses!) and regrettably, I feel, any misfortunate seaman washed up alive in 1588 would not have stood a chance, let alone time to splutter the name of his hometown.

The island’s original name in Irish is “Dairbhre”, meaning “the oak wood”, with the entrance to its harbour called “Béal Inse”. If you enunciate every one of the syllables, of the second, (Vay al ensa), it is easy to understand how Béal Inse became anglicised into “Valencia/Valentia”. It is typical Hobson-Jobson, an English person trying to get his head round the speech of someone in his own territory, doing his best to answer a question.

Helen was a precocious child, with a strong interest in botany which was recognised by a learned Dublin Society when she was eleven. This is fully explored in the other article.

Blackburn Family Antecedents

The ancestral chain on Helen’s maternal side allegedly includes John Knox, he of “the monstrous regiment of women” (1558). I think we can safely say he would not have approved of Helen’s activities.

Also, the connection with the bloodstained silk vest, one of two worn by Charles I on the scaffold to prevent his shivering, lest malicious thinkers should suspect he was afraid. It was by several accounts handed to a Dr Hobbs with whose descendants it remained until at least 1767. The Morning Advertiser of 29 December 1888 refers to a collection of articles owned by the paternal Blackburn family which they contributed to an exhibition of Stuart memorabilia at the New Gallery, Regent Street, including “the second shirt worn by Charles I”. Other information online states that the shirt is now at the Museum of London.

The Thames Haven Dock by Thomas Allom. (courtesy of Meisterdrucke.uk)

Helen & her immediate family

Bewicke Blackburn, Helen’s father, first comes to notice with a colleague, Francis Giles, in connection with the Thames Haven Dock. The two civil engineers had submitted a plan concerning the “intended Commercial and Collier Docks” [together with] “part of the Coal Stores, the Warehouse, the Hotel Dock and Custom House.” (True Sun, 9.8.1836)

Bewicke and Isabella’s marriage announcement appears in the Newcastle Journal, 25.4.1840: “At Ryton on the 21st instant, Bewicke Blackburn, Esq., youngest son of P. Blackburn, Esq., Clapham Common, Surrey, to Isabella Agnes, youngest daughter of Humble Lamb, Esq., Ryton, Durham.” (Humble Lamb JP, whose first name suggests Quaker origins, died suddenly in 1844 when riding in his carriage through the Newcastle streets. The Lamb family were coal mine proprietors in the North of England.)

Census 1841: Bewicke, aged 25, a civil engineer, Isabella, 28, and their baby son Charles aged four months were living at Clapham with Bewicke’s parents, Peter and Jane.

Between the census and Helen’s arrival, Bewicke Blackburn had been appointed Manager of the Slate Mine on Valentia Island. Isabella, possibly pregnant, and the baby Charles went to Ireland with him.

- Helen’s birth was announced on 4 June 1842 in the ‘Dublin Evening Packet’, in the style of the time. “May 25. At Valencia, county of Kerry, the lady of Bewicke Blackburn, esquire, of a daughter.”

Sometime in 1843, Isabella had another daughter, Jane.

- An announcement in the ‘Illustrated London News’, 28 Dec. 1844, shows they had become a family of four children: “At Valencia, Ireland, the lady of Bewicke Blackburn, Esq., of a son.” (This baby is Alexander Bewicke Blackburn.)

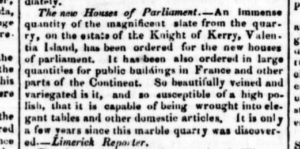

For the slate quarry, these were boom years, with international recognition of the quality of the product:

(Tipperary Free Press, 15.10.1845)

Tragically disaster was lurking just around the corner. The blight of the potato harvest in repeated years plunged Ireland into famine, devastating the Irish population by death and disease, with many more people lost by emigration. For the Blackburns, the horror and grief were more particular, precisely on the 25th and 27th February 1846. One can only imagine the heartbreak behind the sparse newspaper announcement, (Railway Bell & London Advertiser, 7 March 1846):

“At Valencia, Ireland, of scarlet fever, on the 25th ult. Jane Bewicke, aged 2 years and on the 27th ult. Charles Bewicke, aged 5 years, the infant children of Bewicke Blackburn, Esq.”

Baby Jane, and young Charles, who we last saw as a babe in arms at Clapham in 1841.

During the famine, lack of food caused weakness to the immune system, particularly among the poor, which led to added mortality from illness and epidemics. Scarlet fever is not considered one of the primary causes of death in the general population during the famine years, but maybe Valentia was an exception. It is an easy presumption that the better off, like the Blackburns, would have managed to maintain a supply of food, even in the dire circumstances. Ships regularly came into harbour, and they had money to pay inflated prices. Scarlet fever is usually spread by runny noses and coughs. It is quite possible that the complaint was endemic among the children of the slate workers and perhaps spread to the big house.

The Blackburns do not appear to have had any further children. Mercifully, Helen and Alexander survived infancy.

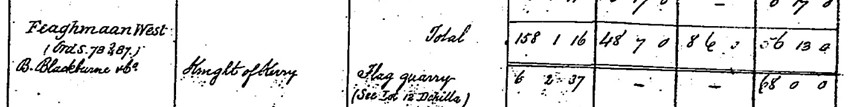

In 1852 we find ‘B. Blackburn’ paying rent for the Flag Quarry at Feaghmaan West. He was by then “& Co” which suggests he was one of the proprietors.

In 1855 Bewicke took Denis Moriarty, a publican of Cahersiveen, on the mainland, to court for stealing from him “a brass ½ let”, (whatever that may be), a case which dragged on for some time at the Petty Sessions with no discernible outcome.

By 1861, Bewicke, 49, a mine owner, Isabella, 47, (ages often varied) and their son Alexander Bewicke, (born Ireland), a scholar aged 16, were in London, recorded at Chelsea. At the same time eighteen-year-old Helen was a visitor to Ryton, staying with her Aunt Jane and sundry other maternal relations. It is unknown whether the Blackburns had permanently left Ireland by then, or if the visit to England was temporary.

By 1871, they were settled in England, described as “lodgers” in rooms at the residence of a chemist and druggist at 6 Royal Parade, Lewisham. Helen, by then aged 28, was with them, but not Alexander, 26, a civil engineer like his father, who was in lodgings at Elish Cottage, Lewisham, with his wife Sarah, and their baby daughter, Helen, 12 months old, who had been born in France.

Between 1865 and 1877, Bewicke and Alexander, singularly or in tandem are noted in lists of patent applications for diverse inventions: “Lubricating compounds for bearings in machinery; improvements for economically consuming fuel in fireplaces; improvements in rafts or stages carrying passengers and merchandise at sea and the means of propelling same; improvements in metallic pens”, and probably more. It is disappointing that I have not yet found Bewicke in a horseless carriage as indicated in Helen’s obituary. Her brother Alexander eventually went to live in California, USA, where he died in 1929.

Helen’s mother, Isabella Agnes Blackburn, wife of Bewicke, died on 8 December 1874 at 14 Victoria Road, Kensington. (Will proved 2 Feb 1875, effects under £100.) I have not found a newspaper obituary.

By 1881, the widowed Bewicke was in Ireland again. On 10 October 1882, Freeman’s Journal, writing on the subject of billiard tables, in which “slate has to be accurately planed on the upper as well as the lower playing surface in order that it may lie closely to the frame” referenced a letter received from “Mr. Bewicke Blackburn of Dublin” dated 16 November the previous year in which he stated “that Valentia slates had been used for this purpose for more than forty years” and that “Mr George Magnus, one of the best billiard table makers, used it not only for the beds but also for the frame and legs and found it less affected by temperature changes and by moisture than by either wood or iron.”

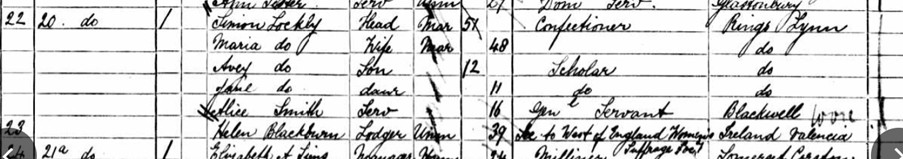

In 1881 Helen was in Bristol at 20 Park Street; she was 39, a lodger in the household of Simon Lockley, a confectioner:

She is described “Secretary to the West of England Women’s Suffrage Society born at Valencia, Ireland.”

Park Street was the HQ of the Women’s Suffrage movement for the West of England. During Helen’s time in our city, she donated her collection of portraits of “historically notable women” to the “women’s hall” at University College, Bristol. (Bristol University was founded in 1876, and from inception admitted women, though as day students only. It is thought that Helen may have lectured there.)

Helen’s parents were from the professional classes and believed in the education of their surviving children, their daughter as well as their son, but I cannot tell what formal education Helen may have received. At aged eleven she was exceedingly bright and would have been encouraged by the reaction concerning her botanical discoveries. She may have been thinking (frustratedly?) of her own experience when she delivered a paper at the Social Science Congress in October 1881 entitled “The higher education of women” in which she specifically bemoaned the lack of adequate provision of higher education for girls in Ireland, her native land:

“……any such teaching power as there exists is drained off to England. This leaves the great majority of Irish girls ill-provided with means of instruction of the advanced kind and diminishes the energy of the country. Foundations with schools for boys and girls exist in which the boys receive instruction in classics, mathematics, or scientific subjects while the girls have only the barest list of accomplishments, often only needlework to correspond to these higher subjects. The amalgamation of classes on the subjects in these schools would be a first practical step towards providing better education for women.” (Paraphrased from The Englishwomen’s Review 15.10.1881)

(Helen was obviously referring to middle-class girls like herself. As in England, poor Irish girls would have only received basic elementary schooling, if any.)

Her time in Bristol was cut short due to the increasing age and infirmity of her father. By 1891 she may only have been visiting when she was recorded at her aunt’s house, 12 Calverley Park, Tunbridge Wells; Caroline Perkins aged 80 was Bewicke’s widowed elder sister. Bewicke was then 79 and residing in the same house, as was another niece aged 28, Alice Leatham, born in Gibraltar. There were two servants, Ambrose Seager, a young footman, aged 17 and Caroline Weston, a middle-aged cook. The two nieces were undoubtedly on call for nursing duties, but fortunately Helen, by then 48, was also able to continue her work as “secretary, national society guild”. (Maybe the “women” part of her job title, omitted from the record would have raised too many lorgnettes in genteel Tunbridge Wells.)

Helen retired as secretary to the Central Society for Women’s Suffrage at Christmas 1894, “due to increasing home duties”, though would carry on as an active member of the Committee to which she offered the aid and counsel of her long experience. Her colleagues gave her a pair of silver candelabra “in affection for twenty years of loyal and devoted work for women’s suffrage.”

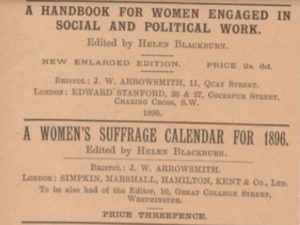

During these years, in addition to looking after her father, Helen was an editor and prolific writer of which “A Handbook for Women Engaged in Social and Political Work”, is an example, published in Bristol by J.W. Arrowsmith of 11 Quay Street, which as the advertisement shows went into at least two editions.

During these years, in addition to looking after her father, Helen was an editor and prolific writer of which “A Handbook for Women Engaged in Social and Political Work”, is an example, published in Bristol by J.W. Arrowsmith of 11 Quay Street, which as the advertisement shows went into at least two editions.

Bewicke Blackburn died in his 86th year in January 1897 at 12 Calverley Park and is buried at Brompton Cemetery. Effects £267. 9s.4d. Probate to Helen. Hardly untold riches.

By 1901, fifty-eight-year-old Helen was living at 18 Grey Coat Gardens, City of Westminster, described as an “editor, author” with a housekeeper Frances Weston, 59.

At her death she was much praised, particularly by the women’s press, and especially by Millicent Fawcett. Her life deserves more than these brief lines.

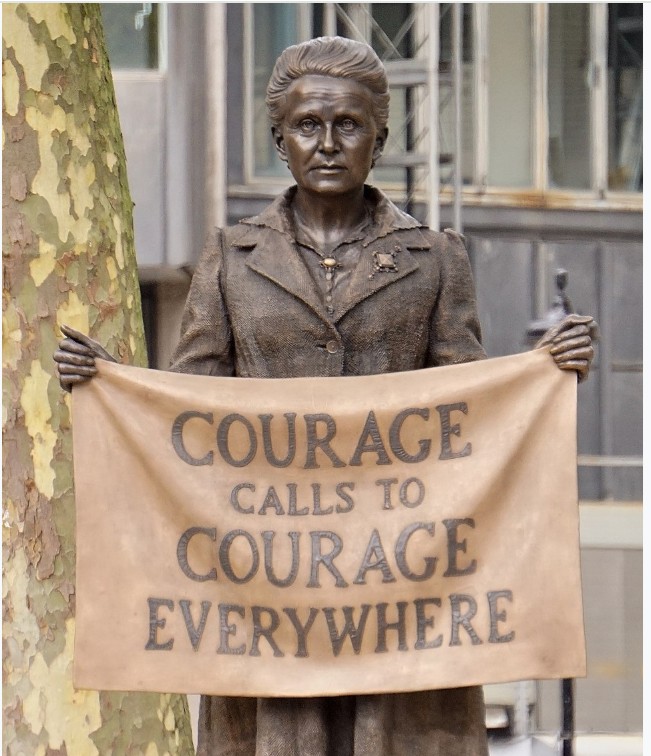

When Gillian Wearing’s statue of Millicent Fawcett was raised in Parliament Square in 2018, Helen Blackburn is one of the 59 women and four men whose names & images are incised around the plinth.

The statue of Dame Millicent Fawcett, Parliament Square.

I discovered Helen through this blog never having heard of her before, but I have added her name to those I will invite to my celestial wine and cheese party which I hope will be many years in the future. She was said to be of a modest nature, who never blew her own trumpet. I hope she will be heard above the babble of my other, noisier, guests, a definite “monstrous regiment”, including myself. We will make her notorious ancestor spit with rage all over again.

End Note. I regret to say that just thirty odd years ago antipathy towards women’s education was alive and well in Clayfield Road. My elder daughter was about to take up her place at university. A neighbour, female, of about my own age, said “I don’t believe in it. Girls. Waste of time and money. They only get married.” First struck speechless, I did manage a protest, but it met with pursed lips.

Even more tragically, Helen would weep tears of frustration for the girls and women under the Taliban regime in present day Afghanistan, as well as all other women in the world denied the basic human right of education.

ooOOoo

Numerous references apply apart from these few, including the Dictionary of Irish Biography which claims Helen as one of their own. Also, see

Leave a Comment