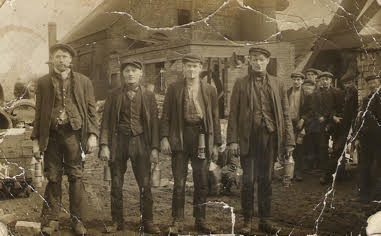

At the “Book Launch” at Kingswood Heritage Museum on 29 November 2016 Mr Roger Curtis who was at the event, sent me this picture (above) believed to be at Hanham Pit, showing his grandfather, Ernest James CURTIS, (known as Jim) and others. Roger told me that Jim

“was born on 21 January 1892 and as he looks like a teenager, this would maybe date the picture to about 1908-10. I have no idea of the names of the others in the photo. The one on the left appears to be somewhat older than the others. I especially like the little chap on the left peeping out of the truck.”

In the census of 1911, the Curtis family were living at Vicarage Road, Hanham, all born either Oldland or Hanham:

- Thomas Curtis, 66, stone cutter

- Charlotte, wife, 59, b Oldland (married 25 years, 7 children, 6 living)

- Henrietta Alice, daughter, 24, coat baster, outfitting

- John Henry, son, 23, stone cutter

- Ernest James, 19, son, drammer, coalminer

- Frederick, son, 18, labourer, mechanic

- Gladys, daughter, 15, laundry hand

- Violet May, 10, school.

Ten years before, in the census of 1901, they lived at “Ragged Road, Kingswood.”

Jim married Caroline Peters in 1912 and by 1939, he was a fitter at a motor works, living at 5 Vicarage Road with Caroline and two children, William, (born 1917), a bus conductor and Dorothy, (born 1926) a scholar.

Roger remembers “the cottages at Vicarage Road, with gas lamps, cess pit, hens running around, and a huge garden that backed on to Hanham Church. Jim and Carrie moved into a bungalow in Tudor Road about the mid-50s and the cottages were demolished to make way for modern housing.”

He adds:

“I’ve just finished reading ‘Killed in a Coalpit’ and thoroughly enjoyed it. You’ve done a wonderful job.”

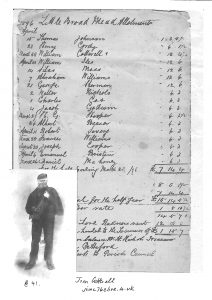

Mr Jim Cotterell has supplied me with a photo of his ancestor William COTTERELL at the age of forty one. He is carrying a tool that looks like a poker. This is attached to a sheet giving a list of names of holders of “Little Broad Mead Allotments” in 1896.

Mr Jim Cotterell has supplied me with a photo of his ancestor William COTTERELL at the age of forty one. He is carrying a tool that looks like a poker. This is attached to a sheet giving a list of names of holders of “Little Broad Mead Allotments” in 1896.

Jim said: “William Cotterell, known in the family as ‘the one armed Chimney Sweep’, was born on 8 February 1855 in Tormarton. We assume he was injured in Parkfield Pit as on one census he is registered in hospital. He had 8 children (all but one with his wife). One of his sons, George Cotterell, born 1886 (my grandfather) worked at Parkfield as a ‘belt boy’. My father, William Henry (Bill) Cotterell started work aged 14 above ground at Parkfield. He never mentioned this to me until 1967 when I started work at Fantasie Foundations…”

(“What a brilliant name for a corset factory!” I remember it well!)

Jim continued “…..as a sewing machine mechanic. One of the management team asked if I had a Bill in the family, then went on to say that they had started work together and that his Father was the mine electrician.”

Confirming Jim’s information, in the census of 1891, William Cotterell, 36, was a coalminer, born Tormarton, living at Parkfield Road, Pucklechurch with his wife Elizabeth, 38, and their children Henry, 10, James, 7, George, 5, William, 3 and Susan, one.

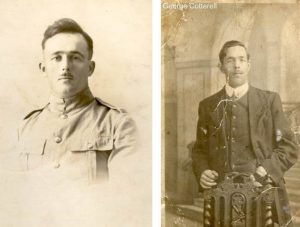

Bill Cotterell (left) He enlisted in the Royal Marines after 3 years working at Parkfield Pit. George Cotterell (right) former ‘belt boy’ at the colliery.

By 1901, William had become a Chimney Sweep. Henry had left home and was working in Wales as a railwayman; James, 17, and George, 15, (Jim’s grandfather) were both “coalminer, belt boys”. William jun. was 13, Susan, 11 and an addition to the family, Edward Charles, aged seven. By 1911, Edward too was in the mining industry as “a miner’s labourer, above ground”. William died aged 76 in 1931.

Mr Brian Palmer gave me a photo of his ancestor William PALMER, with his wife Mary Ann outside their cottage at North Common, Warmley. The lives of William and Mary Ann as revealed by Brian, shows there is so much more to be learned about the people whose stories are told briefly in the book.

William Palmer married Mary Ann King at St Mary’s Bitton onChristmas Day, 1880. Mary Ann had lost her father Aaron King, (page 108) when she was 10 years old. He died from injuries received when a stone fell on him whilst at work at Deep Pit. Afterwards, with five other children to care for, her mother, Rosina, eked out an existence as a rag picker at North Common where William and Mary Ann also brought up their family. In 1901 they are listed:

William Palmer married Mary Ann King at St Mary’s Bitton onChristmas Day, 1880. Mary Ann had lost her father Aaron King, (page 108) when she was 10 years old. He died from injuries received when a stone fell on him whilst at work at Deep Pit. Afterwards, with five other children to care for, her mother, Rosina, eked out an existence as a rag picker at North Common where William and Mary Ann also brought up their family. In 1901 they are listed:

- William Palmer, 46, colliers’ labourer, born North Common

- Mary Ann, wife, 40, born Moorend

- Florence, dau, 17, rag sorter, paper mill,

- Aaron Palmer, son, 15, heel lift, shoe factory

- Aleck Palmer, son, 10.

William was killed in 1908 at Deep Pit, St George (page 122). Brian kindly provided me with a press cutting of the inquest (WDP 4.2.1908) from which I was interested to note that he was “a good servant and bore an excellent character” however it was stated that “it was not part of the man’s duties to go up the incline. He had no business there.” The verdict was “accidental death”; as with a surprising number of cases it was decreed the man concerned was responsible for his own death. It strikes me as suspicious that so many experienced miners were deemed to have been careless with their lives.

I was previously unaware of the King/Palmer connection and that the family had been doubly bereaved.

The death of George MILLS, (page 116), aged 21, a donkey engine man, is another that might bear scrutiny and the following has come to light. His widow Lucy (nee Derrett, married at Fishponds 17 May 1884), who had given birth the day after George’s death, brought an action against the Rangeworthy Colliery Company for £140. 8s 0d which represented three years wages, the most that could be claimed under the Employers’ Liability Act. Mills had been excavating props when the stone fell on him, from which he later died. Various witnesses were called to prove there was no negligence and Richard Donald Bain, the Mines Inspector, stated the cause was “a sudden creep of the ground”. Lucy’s claim was dismissed. (Bristol Mercury 14.6.1886) Before her marriage, she had been a servant. In 1891 she was working as a cook at Westbury-on-Trym. Her baby son, George Francis Henry Mills “aged 0” died between June and September 1886 when his death was registered at Barton Regis. The Good Old Days? I don’t think so.

When looking for Lucy Mills, I discovered a “Killed in a Coalpit” which I regret was omitted from the book. William JENKINS was killed at Rangeworthy Colliery whilst working with his sons and others, once again engaged in the hazardous “propping a stone”. The stone, 3 tons in weight fell on him injuring his back and thighs. He was “conveyed home” but died within half an hour, probably from shock or concussion. The verdict (Bristol Mercury 3 May 1873) was, as usual, “accidental death”. Two years before on the 1871 census William was aged 60, living at Rangeworthy with his wife Hannah and one of their sons, John, aged seventeen.

Ms Mary Clements has drawn my attention to a mistake in a date. Samuel CLEMENTS (page 64) was killed in a fall of earth whilst working for J.J. Whittuck (page 234) of Hanham Hall in 1869, not 1867. Sorry about this. “The poor fellow was heard to speak but by the time he was got out, life was extinct. He was 44, lived near the Rise & Crown, Two Mile Hill, and left a widow and six children.” (Bristol Times & Mirror, 27.2.1869; this newspaper has appeared on line since I finished the book.)

Another contact was Mr J. Martin Warr concerning Ted POWELL (Chapter 11, page 223 etc). Many years ago Martin was given a “G. Clamp” by Ted’s daughter which had his name stamped on it. I put him in touch with Lynnette Bartlett-Sutton, Ted’s granddaughter, who donated all the pictures of Ted; she is naturally thrilled by the acquaintance. Both Martin and Lynette have kindly agreed that the clamp which….

“carries a large letter ‘G’ the tail of which screws in or out against the top of the ‘G’ to hold two pieces of metal together; used for drilling etc.”

“……should be donated to the SGMRG archives”. Martin says that the thing would be “excellent for cracking your walnuts at Christmas, but watch your fingers!”

He goes on “In the early 1950s I watched the civil engineering works in Downend when they were drilling test bores for the mine which ultimately opened at Harry Stoke. This was a drift mine, not one with a vertical shaft. When it opened they recruited workers, one of whom was the son of the BENCE family of Kingswood who moved into ‘Cave Cottages’ in Downend, just below The Green Dragon public house. He, Trevor, lost his arm very soon after joining when it was jammed between the truck on which he was travelling down the drift into the mine and the wall lining the passageway.

“Accidents happened right to the very end. Your book has done a great deal to bring the efforts of those hard working souls into the broad light of day. One can otherwise only imagine the privations that they endured for a pittance.”

I was especially pleased to see Ms Jean Hodges and her sister Pam at the launch: their grandfather Thomas ELSBURY is shown on page 97. I met Jean years ago and tried to contact her for permission to use Tom’s photo but she had changed her address and phone number. Luckily, she was more than happy that I used both it and her original research.

At a meeting at Bitton, Doris Golding kindly gave me the picture of her father-in-law, Walter Golding, with another coalminer, at Speedwell Pit in about 1923 when he was aged about forty. Such pictures of men at work underground are like gold dust.

A shorter version of this article appeared in SGMRG Newsletter no. 48, Winter 2016/17.

Leave a Comment