“Around 1700, a strange noise began reverberating around British mineshafts. That noise – harbinger of the Industrial Revolution – was subtle at first, but it grew louder with each passing decade until it enveloped the entire world in a deafening cacophony. It emanated from a steam engine.” (Yuval Noah Harari. “Sapiens. A Brief History of Humankind”.)

This power, though no one realised it, had been there forever, or at least since every pan or kettle with a lid was filled with liquid and put on the hearth to boil. If the pan boiled fiercely the lid flew off. A woman, maybe distracted for a moment, would have grumbled as she mopped up, unlucky if the pan held a “mess of potage”, (a situation I know only too well), or worse still, it also put the fire out. With her man busy doing “man things”, with a pick and shovel, neither noticed the potential. Heat had been converted into movement. The boiling water produced steam. The steam expanded causing the lid to fly off. Give it a few thousand years or so.

This power, though no one realised it, had been there forever, or at least since every pan or kettle with a lid was filled with liquid and put on the hearth to boil. If the pan boiled fiercely the lid flew off. A woman, maybe distracted for a moment, would have grumbled as she mopped up, unlucky if the pan held a “mess of potage”, (a situation I know only too well), or worse still, it also put the fire out. With her man busy doing “man things”, with a pick and shovel, neither noticed the potential. Heat had been converted into movement. The boiling water produced steam. The steam expanded causing the lid to fly off. Give it a few thousand years or so.

In Allihies Museum I strolled over from my lists of manpower, to see what George and Kevin were up to. They were studying the result of the above in rapt attention. Behind the glass was an example of moving machinery. A model of a steam engine. As the water heated, the steam expanded and pushed a piston connected by wire which moved the wheel up and down. It was mesmerising.

In 1841 Frederick Roper reported on the Allihies mines: “There are five powerful steam-engines, two for pumping, two for drawing up the ore, and the other for the crushing and stamping machines, alternately.”

In 1841 Frederick Roper reported on the Allihies mines: “There are five powerful steam-engines, two for pumping, two for drawing up the ore, and the other for the crushing and stamping machines, alternately.”

“Puxley’s Engine House, built 1845, housed a near relative of those described. It contained a pumping engine with a steam cylinder 52 inches in diameter. The depth of the shaft was 440 feet.

“Puxley’s Engine House, built 1845, housed a near relative of those described. It contained a pumping engine with a steam cylinder 52 inches in diameter. The depth of the shaft was 440 feet.

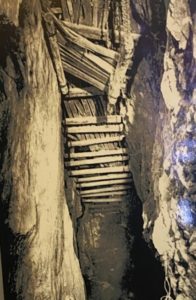

An engine brought the mined ore to the surface, but the men still descended and ascended in primitive fashion via a series of ladders.

The agony of this exhausting toil brought on howls of shock, anguish and almost hot tears from my two men.

I said, annoyingly, that I was not surprised by it as I had written about it before in 2023. Such a system was employed in the Laxey Mines of the Isle of Man, and my version came from a newspaper reporter’s graphic account, written from his own experience in 1875; no pictures, but you can’t argue with the authenticity of a newspaper’s date printed on the top of the page. [1]

In 1856 the Mountain Mine at Allihies went down more than a thousand feet underground. Puxley calculated it took each miner 10 seconds to descend about 3 feet of each rickety ladder, and much longer to come up, a huge waste of energy, time and money.

In 1856 the Mountain Mine at Allihies went down more than a thousand feet underground. Puxley calculated it took each miner 10 seconds to descend about 3 feet of each rickety ladder, and much longer to come up, a huge waste of energy, time and money.

Plans were put into place.

By 1862, the Man Engine, technology invented in Germany but adapted in Cornwall, was installed at the Mountain Mine in a purpose-built shaft. Hundreds of miners could be transported up and down the mine at the same time with stopping off points in the manner of an escalator.

(For an RTE TV programme, see https://www.facebook.com/watch/?v=221040792526110)

The Cornish Man Engine House of Mountain Mine is unique, not just for being the only one constructed in Ireland, but the sole surviving example of its kind anywhere in the world.

The Cornish Man Engine House of Mountain Mine is unique, not just for being the only one constructed in Ireland, but the sole surviving example of its kind anywhere in the world.

The shaft was more than 1,400 feet deep, 918 feet of which were below sea level. The Engine House structure, which was conserved in 2004, stands as is a symbol of Allihies’ rich mining heritage and the lives of the copper miners who worked there.

The Man Engine may have had its origins in finance rather than philanthropy, but it was a godsend to each individual miner. They must have all whooped for sheer joy.

Though, very sadly, you could say “we mucked up”. The new technology of the 1700s and the Industrial Age which followed had unforeseen results. Ultimately in a few hundred years it would lead to the world we know today and therefore responsible for one of the major avenues which could eventually lead to the extinction of humankind itself. Global Warming. But let’s not get too morbid. For the moment we are

“Done with complaints, museums, libraries, querulous criticisms, afoot and light-hearted we take to the open road…”[2]

….or at least out into the open air in glorious April, 2025 gazing up at the landscape above the Mountain Mine[3] and the Engine House which looms over it like a castle.

The necessity for CAUTION is all around ……the danger obvious

I could lie and say we trekked all the way to the top, but we are too rickety. The publicity would be the undoing of Brutus Tours and personally embarrassing, so the honour of being up close fell to Kevin alone……

I could lie and say we trekked all the way to the top, but we are too rickety. The publicity would be the undoing of Brutus Tours and personally embarrassing, so the honour of being up close fell to Kevin alone……

……. with even the opportunity to do a bit of bird watching……. or at least one feathered friend which looks (to me) like the bird from ‘The Detectorists’, my all-time favourite TV series. If you are a fan you will understand.

……. with even the opportunity to do a bit of bird watching……. or at least one feathered friend which looks (to me) like the bird from ‘The Detectorists’, my all-time favourite TV series. If you are a fan you will understand.

Within a few years of building the Engine House the latest Mr Puxley sold up to another consortium. By the 1880s the boom times were over, and the mine complex closed. Many local people, both Irish and of Cornish descent left Berehaven, some forever, often to work at the mines at Butte, Montana where some tragically met the fate they had successfully avoided at home.

Within a few years of building the Engine House the latest Mr Puxley sold up to another consortium. By the 1880s the boom times were over, and the mine complex closed. Many local people, both Irish and of Cornish descent left Berehaven, some forever, often to work at the mines at Butte, Montana where some tragically met the fate they had successfully avoided at home.

The Cork Daily Herald of 19.11.1892 relayed the sad news, “DEATH WITHOUT WARNING – A Berehaven man killed in America.” A man named McCarthy, having finished his own work was helping his comrades when he was hit by a bucket (the contraption which lowers and returns men or yields up and down the mine). In an incident near the surface, he was knocked unconscious and though conveyed to hospital died twenty minutes later.

(Anyone reading KIACP will not be surprised that there was an inquest, wherein everyone was exonerated. “Accident”, being the universal mining verdict.)

McCarthy was 26, “an able man, leaving a wife and two children unprovided for”, another familiar phrase, with the addition “he occasionally sent money to his parents at home.” His death followed a recent “cave-in” at the same works, when four or five other Berehaven men (unnamed) lost their lives.

Although during the journey to the hotel, Algernon resumed his strict commands to “Look at the View!”, for the antique clientele of Brutus Tours it had been a very hectic few days They were finally done in.

“Time for Bed, said Zebedee….”

[1] See blog “The Great Laxey Wheel”.

[2] Apologies to Walt Whitman for the misquote.

[3] The area famously known as “Hungry Hill” the title of a novel by Daphne du Maurier, her depiction of the Puxley family, re-imagined as the Brodricks.

Leave a Comment