On 9 April 2025, three of us, George, Kevin and me, were in Ireland; George is a native Irishman, Kevin, a passport holder, and me, a Brit, without a red corpuscle of Irish blood, cannot show my disdain for Brexit in the same way. We flew into Cork, the trip arranged via an outfit, entirely fictional, called Brutus Tours Ltd. Geriatrics a Speciality. Proprietor: Brigadier (and Chauffeur) Brutus Algernon Short-Shrift. “Stand up straight there! No slacking in the ranks! Pay Attention! Look left! Look right! Look at the View!” Despite the uncompromising advertising, I cannot fault the tireless organisation, research, conduct and good humour (mostly) of Brutus Tours, and hope to use them again unless they are purposely fully booked or require notes signed off by several doctors and/or High Court judges. But enough of this silliness.

Our first night’s stop was at Kinsale, a blameless seaside town, which I recall from a riotous three days, no harm done, I spent there nearly sixty years ago. I need hardly say this was before I took to double-harness.

In sober contrast this time, the first stop proper on our journey along the Wild Atlantic Way was the Old Head of Kinsale, fittingly chosen for the Lusitania Memorial, the Cunard passenger liner, torpedoed 7 May 1915, which commemorates the lost souls and survivors alike.

Even before we arrived at the Memorial itself, there was a bonus, an unexpected nudge of family history, a Triangulation Pillar, which marks the network of surveying stations used by the Ordnance Survey of Ireland.

In the first quarter of the 20th century, George’s Danish-born grandfather, Arthur Lindegaard worked intermittently in Ireland as a lithographer for the OS, which explains our surname, and the long family association with the country.

George pays homage to the grandfather he never met.

This is me, reading about the Davit.

The Lusitania Memorial Garden contains one of the largest artefacts recovered from the wreckage of the ship, a davit, a 3 metres high crane, which was used to lower lifeboats into the water. It is placed to point directly to Lusitania’s last resting place in the ocean, 12 miles south of the Old Head.

The beauty of going away in April is that we almost had the place to ourselves.

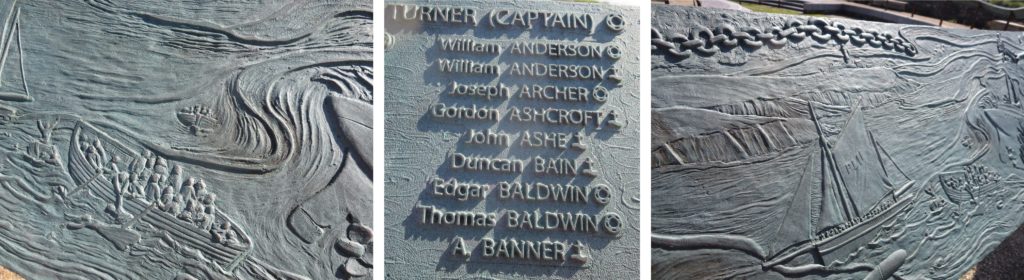

Around the rim of the semi-circular rings of the monument known as The Wave are engraved the names of the passengers and crew; against each name is a symbol, a circular lifebuoy for those who survived, a cross on a wave for those who perished.

The carvings on the frieze depict scenes from the epic rescue. PL11 is the fishing smack, the Wanderer of Peel, Isle of Man.

A serious George looking at the panorama from the Tower.

The Museum:The Old Head Signal Tower, dating from 1804-1806, is one of the buildings we know as Martello Towers in the UK, which were built all along the coasts of Britain and Ireland to watch for any threat of French invasion. The ground floor contains Cunard memorabilia, including the portion of Atlantic cable, pictured later in the text. The first floor contains Lusitania artefacts, inlcuding a deckchair – again see the text – with stories and donations from many who were associated with the tragedy. The top floor explains the work of the Tower’s restoration.

Before leaving the Lusitania Memorial I had a chat with Diarmut, a genial volunteer, an “old fellow”, though younger than me. I said I was getting on, too old for all this racing about. He disagreed heartily and said we must live life to the full, and shared the advice he had received as a boy from his grandfather: “Live as long as you can and don’t die until you have to.”

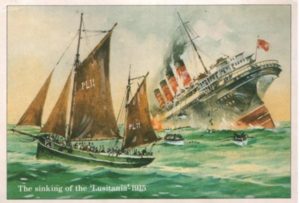

London Illustrated News, May 15, 1915, engraving Norman Wilkinson.

The Lusitania, a British Cunard Liner, sailed from New York on 1 May 1915 with passengers and crew numbering 1,962. On 7 May, at the Head of Kinsale, off the coast of county Cork, the ship was torpedoed by German UBoat 21.

1,192 people lost their lives. England had been at war with Germany for eight months.

There were 771 survivors of the sinking of the Lusitania.

Wherever I go, I try to find Bristol connections. Before our visit, I vaguely knew that there were a few people among those who survived, but I didn’t know any names or circumstances. The research had to wait until we returned home. I can now tell the stories of the Bristol survivors:

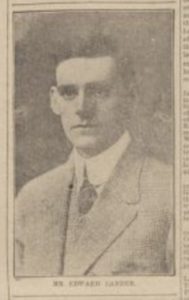

Mr Edward Lander, a businessman, formerly of Bristol, who had been working in the New York office of a London firm for the past eight years was returning home for a short stay. Primarily for business, his trip was also an opportunity to visit his widowed mother, who lived at 5 Logan Road, Bishopston. His wife, who came from Chicago, and their child, did not accompany him. There had been a German warning of a possible attack, which alarmed his Bristol friends, though in the US, those intending to travel were more blasé about the danger.

After an uneventful voyage from New York, Friday morning, 7 May, dawned foggy, but by the time the Irish coast was sighted, the fog had cleared, and visibility was fine. Passengers on deck eagerly watched as landfall grew closer, while others were quietly eating lunch in the dining room, including a Mrs Fish and her younger daughter. Mrs Fish was travelling with her three children and her sister Miss Rogers.

Mr Lander was on deck on the port side alongside Miss Rogers who was holding Mrs Fish’s baby, whilst the elder daughter, Eileen Fish, played close by. During the voyage, Lander had become friends with the women, who were also Bristol bound. In those more formal times, people did not get on to Christian name terms within so short an acquaintance. Lander’s attention was suddenly drawn to a strong wake, less than an eighth of a mile distant, travelling at speed. Other onlookers thought it must be a dolphin, but before they had chance to rethink the idea, a missile struck the Lusitania amidships. Lander heard someone cry out “It’s got us!” with which the torpedo exploded, “not making a big racket, but we saw a big cloud of smoke. The engines stopped and the vessel took a list to starboard.”

People crawled onto the first cabin deck, which was already running in water. Lander seized the baby and gripped Miss Rogers by the wrist. He was still holding the baby as they scrambled into a lifeboat on the boat deck, which was so full there was no room to turn round.

“Somebody came alongside and said ‘It’s all right. She’s on the bottom.’ Thinking by this it was safe to return to the ship,” Mr Lander said, “we all got off our boat and went aboard the Lusitania again. Doubt soon arose as to the safety of the ship, and people began to get into the lifeboat again.”

Suddenly the Lusitania sank. The boat was attached to the liner by a rope; Lander, Miss Rogers and the baby hurtled down against the steep side of the ship.

“The baby was wrenched out of my arms as I hit the sea, and I turned over and over.”

By the time he came up for the second time, he could see no sign of Miss Rogers or the baby, but “struck out a little” for an overturned flat-bottomed boat with one man on top of it. He reached the boat and lay there, almost unconscious. He was starting to recover, when they saw a woman’s dress in the sea.

“Merely the back of the garment was showing. The man got hold of the woman’s head and I held onto her clothes. We pulled her onto the overturned lifeboat. Soon after, we saw a collapsible boat with six men in her, members of the crew, I believe. Her side was stove in, but she kept afloat. We hailed her: she came to us and they took us on board. I was shivering greatly and one fellow who seemed in command, [1] told us to take an oar. The pulling worked up the circulation and made me feel better. Then someone else took a turn in pulling, and I was put back on the bottom of the lifeboat again. There were many people floating around; we saw two men and a woman hanging onto a tank boat. Those people were afterwards rescued by the collapsible boat. Our lifeboat was allowed to drift for a time until she was secured to the collapsible by a rope. Boats dotted the sea and hope was raised by a little fishing smack which could be seen in the distance. There there was not much wind however, and the smack went towards the coast instead of coming to us. Possibly she had as many people aboard as she could take.

“There were lots of deck chairs floating around but we saw only one that was being used as a means of support, and that by a woman who also had a life belt. The collapsible boat picked up about half a dozen people while cruising about and remained thus engaged a long time, until we managed to cry for HELP in chorus. After we had been on the water for about a couple of hours HMS Bluebell, a government tug or patrol boat, came to our assistance and we were picked up. The crew of the Bluebell were very good. They gave us steaming hot tea, and after changing some of my wet things, I went to sleep . Two or three hours later we reached Queenstown but were delayed in getting ashore, owing to the number of boats before us.”

(On the Bluebell there were 47 survivors, and 19 dead. Among the survivors were Lusitania’s Captain, William Turner, a man of a bluff demeanour, to whom passengers were “a load of bloody monkeys, constantly chattering” and Lady Mackworth, 1883-1958, the future Lady Rhondda, the suffragette and campaigner for women’s rights.)

Edward Lander

“It was 11 o’clock at night when we landed. At Queenstown we were told by Cunard to send what telegrams or cablegrams we liked. I dispatched messages to New York, London and Bristol. A soldier there took us in charge and got me some clothes, so that I might return the garments borrowed on board the Bluebell. The Queenstown people were very kind. The American consul was there and advanced money to those who needed it, English as well as American. Mr Bryan, the US Foreign Secretary, who then had no idea of the appalling nature of the calamity, sent a cable asking for the names of the American survivors to be wired to him.”

In answer to questions, Mr Lander said he was told the Lusitania went down in a depth of about 60 fathoms at the time of the partial settling. Asked if the declaration of safety seemed curious in view of the possibility there had been a second torpedo, he was unable to say whether there was a second torpedo or not. Some of the survivors had kept their lifebelts as souvenirs. There were not many available for those who had been on deck when the disaster occurred, but seemingly plenty of these aids for those who had been below.

With the other survivors who were Bristol bound, he travelled home via Rosslare and Fishguard.

Mrs Sarah Fish and her daughters, Eileen aged 10, Marion, 8, an infant aged six months, plus Miss Rogers, were travelling from Toronto to Bristol for the duration of the war. Her husband, Lieutenant Joseph Fish, “a well known Bristolian, went to Canada three years ago and has taken a commission with the Canadian Expeditionary Force.”

When the torpedo struck , Mrs Fish and Marion were below while Eileen was on deck, with Miss Rogers and the baby.

Warnings of a possible German attack had been the subject of much banter [2] on the high Atlantic, but as the coast of Ireland loomed, and with it the danger zone for lurking UBoats, the bravado ceased. Most sensible people longed to reach Liverpool as soon as possible.

When the ship was struck, Eileen Fish ran below, and despite the rush, was lucky to find her mother. All three ran up on deck, during which Edward Lander, still clinging to the baby and Miss Rogers had been carried down by the lifeboat attached to the sinking ship. Miss Rogers surfaced despite the heavy coat she was wearing, but later could remember nothing from when she hit the water until she came to in Queenstown.

Meanwhile Sarah Fish and Eileen, wearing lifebelts provided by a stranger, were still on the ship as she sank, with Mrs Fish carrying Marion in her arms. They were carried overboard into the sea. When they surfaced there was no sign of Eileen. Mrs Fish called out for help to some people who were in an upturned boat, but they said they could not take her as there was no room. They told her there was an oar floating behind, and if she could get hold of it she could stay afloat with the support of the lifebelt. Mrs Fish did not have the strength to keep Marion above the water the whole time, but eventually managed to get the oar under one arm, while still supporting the child with the other. She believed they had been in the water half an hour when she was helped on to the upturned boat. Her daughter appeared to be dead at his time and others on the boat said she must be put overboard, “but working alone, with the greatest pluck for over an hour at artificial respiration, Mrs Fish succeeded in bringing the child round.”

Subsequently Mrs Fish and Marion were taken off by the collapsible boat, and on this boat, remarkably, Mrs Fish found ten year old Eileen who had spotted it soon after she came to the surface. She had the presence of mind to catch hold of a lady’s cape which was hanging over the side, and was pulled into the boat.

Mrs Fish and the girls were brought to Queenstown, and it was there or at Cork railway station that she was amazed to find her sister, Miss Rogers who had no memory of the events or what had happened to the baby. There was even more astonishment when Edward Lander found them. With the comfort of the reunion they must have mourned the circumstances of the baby’s loss. The two women spoke in glowing terms of Mr Lander’s conduct, and in turn he expressed gratitude to the superb crew of the Bluebell and the great kindness of the Irish people towards the survivors. Mrs Fish, Miss Rogers and the two girls arrived safely on Sunday morning at the home of her mother-in-law, Mrs Joseph Fish, 84 Coldharbour Road.

Mrs Albert Edward Adams, the daughter of Mr A. Pollett, of 23 Bishop Street, St Paul’s, a second-class passenger, who was with her 2½ year old daughter, Joan Mary, had also been living in Canada. Her soldier husband, a stretcher bearer with the 4th Battalion, the Ontario Regiment, was at the front when he read the news of the disaster.

It was about 2.15pm when Mrs Adams heard a dull boom and the ship trembled slightly. Everybody started for the doors of the saloon. She grabbed her little girl, but one of the stewards assured her there was nothing to be scared about.

“I think we have run aground, or something,” he remarked, but then everything on the tables began sliding onto the floor.

Joan Mary Adams, lost at sea.

Mrs Adams went to the deck above and on to the boat deck. A steward helped her on to the top of a canvas-covered boat, but in a minute or two came the order “Women and children this way,”. Mrs Adams, holding baby Joan, was given a lifebelt, and “told to keep quiet, as the Lusitania was practically unsinkable” (a myth which may have been greeted with hollow mirth in memory of 1912.) Then the ship gave an almighty lurch, water poured in and a woman carrying a baby was hurled down the slanting deck on to steps below. There was another lurch and the ship sank, dragging Mrs Adams and her daughter down with it. When they came to the surface, she made for a piece of floating wreckage and rested the child on it.

“But I could not help her, more than just hold her, and watch her die. A young fellow nearby offered to take my baby while I tried to reach a tank floating a little way off, but she had passed away by then. I felt I must kiss her goodbye.”

“The young man helped me towards the tank on which there were several people. It seemed we were drifting for hours clinging to that tank. Many others were in the water. Once the tank was capsized by one of the men, and we were in the water again. It was 23 minutes past two when I left the Lusitania and after 11 when I was taken ashore by HMS Bluebell.”

At Queenstown she was wrapped in a military cloak, and with two other ladies was driven by an Irish woman to her house in Cork. The Irish lady gave them warm food and rest and drove them to the station the next morning to catch the connection to Rosslare. It was disconcerting for the survivors to be told that the ferry had recently been chased by a submarine.

Mrs Adams stayed up with the crowd during the crossing. “We gazed at the lighthouse in thankfulness that the worst was over. The soldiers and sailors at Fishguard did everything they could for us.”

Henry George Burgess. “A Bristolian’s Thrilling Story” was the headline, in the Western Daily Press, 18 May 1915. Mr Henry Burgess of Lamorna, Manor Road, Fishponds, had sent the paper a letter received from his eldest son, Henry George, aged 37. Henry junior had been booked to travel on the Cameronia, but at the port, he found that ship had been requisitioned by the British Government for war service. He was told immediately to board the Lusitania instead, her sailing delayed by two hours for the purpose. Copies of the Sun, a New York paper, containing the German warning, were available on board but the passengers did not take the danger seriously.

Henry was having lunch in the dining room when the first shock came, but he says he kept cool and went two decks below to put on a life jacket. There were plenty available in all the staterooms, and he thought more people would have been saved if others had done the same; when the time came, the life jacket kept him afloat. The boat deck was all confusion, with no-one knowing what to do. The vessel had been struck on the starboard side and taken a tremendous list. There was a terrifying incident when the first lifeboat containing women and children was lowered; it was smashed to pieces with the occupants thrown into the sea. Two or three minutes later, he experienced the second list:

This is a tiny portion of the Atlantic Cable via which the radio operator could send messages. Photo taken by me, 10 April 2025 at the Lusitania Memorial & Museum, Old Head of Kinsale. Note “Brean in Summerset”!)

“No doubt caused by the second torpedo and it appeared to me the ship was going down. The Marconi operator came out of his office and began to take photographs. I don’t know whether he saved himself or the photographs…….” [3]

“I made-up my mind it was time to go. I jumped into a boat which was hove over the side of the ship with not many in it. One of the funnels of the great ship was heeling over immediately above us and we were crowded into one corner of the boat. Either I fell or was thrown out of the boat. Fortunately, I was able to seize a piece of wreckage and found myself alongside a lifeboat which was full. They pushed me away. One of the boat wedges supported me comfortably until I was able to get into the collapsible boat.

“A valet (?) called out, ‘All right, Burgess. You’re in a bad way. Hold on a moment until we’ve taken in this lady,’ (who was hanging on with an oar.)

“I then had a hand in pulling up seats in the boat, (to make more room?) which took nearly an hour. All about us were overturned boats with people clinging to them. We were afraid to approach them lest they should swamp us. Mr Charles E. Lauriat of Boston who we had appointed captain of our boat decided we should take one man who was hanging on to a lifebuoy and then row for the shore. Although 8 miles away, we could clearly see the lighthouse on the Old Head of Kinsale. After a while we came to this fishing boat, the Wanderer from Peel in the Isle of Man and were taken aboard, the third and last boat to be picked up. A collapsible and another lifeboat were taken in tow, until the occupants were taken aboard a minesweeper. Patrol ships and steamers of all kinds by then had arrived on the scene. This was about two hours since the Lusitania had gone down.”

The “Wanderer” of Peel, IOM, which saved Henry Burgess and was seen in the distance by Edward Lander.

“At Queenstown everything possible was done to minister to the survivors and clothing was given without cost, the Cunard company having evidently provided for this emergency. In my boat was Mr D. A. Thomas, M.P.

“I started from Montreal on my return journey with five business friends and of the six, four have been saved from drowning at the hands of the Germans. I arrived at my destination Bradford, Yorkshire, on Sunday morning.”

This trio of survivors were bound for Mrs Veals’ father’s house in Clifton. There is little said about them in local newspapers of the time, except the above photos and in the odd snippet, as when they supported the Lord Mayor’s Lusitania Fund, personally taking the collection at the Globe Picture House in St George. (Mr Veals was later the manager of the Park Cinema, also at St George, both venues I remember from when I was young.)

Bert Veals and Agnes Maud Bailey were married at St Nathanael’s, Redland on 14 October 1909. Bert had previously been a soldier, 7 years in the Gloucestershire Artillery, when he signed up for the Army on 10 December 1915, occupation “Cinema manager”, evidently not considered incapacitated in any way from his Lusitania adventure. He was “Acting Lance Corporal” when released by the army in 1919, then described as “unfit for further service”.

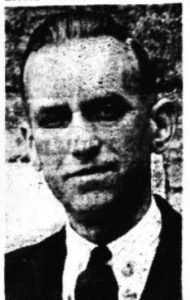

Agnes & Bert Veals, captioned as “Mrs & Mr Veale” in Western Daily Press

Bert Veals’ account of their survival can be found years later in the Somerset Guardian & Radstock Observer, 5.5.1939, when Mr Veals was Mine Host at the Waggon & Horses, Peasedown St John.

They were coming towards of the end of an enjoyable voyage and after dining on 7 May, they were up on deck, looking out to sea, laughing and chatting. Someone said to Agnes, “Look Mrs Veals! There’s a porpoise!” From that moment, Bert says, he knew the ‘porpoise’ was the wake of a submarine.

“The next second, the torpedo was on its way towards us. It left a little white trail behind. In another four seconds it struck the ship six or eight feet to the left of where I was standing. The outline of the torpedo was clearly visible as I looked over the side. There was a most awful explosion. As I grabbed my wife it seemed as though the whole ocean poured onto us; we were drenched to the skin immediately. As the spray came over us, the stern of the vessel lifted in the air, and we were nearly crushed in one of the huge funnels as it came down over us. The next second the boilers burst and out through that very funnel came tons and tons of the most inky black water imaginable.

“We scrambled up to the boat and seeing there was only a few people in it I threw my wife in, much against her will, for she did not want to part from me. I persuaded her it was all right and I would be with her in a minute. There was now a big list on the ship, causing a gap of about four feet to the boat, but I managed to half sling and half throw women and children across the gap where the boys in the boat caught them and dragged them in. As the last woman was got in the boat, Lusitania began to sink more rapidly. I jumped in, just in time, as the boat was barely unhooked from the davits.

“We were all black from the dirty liquid, amidst the most terrible screaming from men, women, and children, but our troubles were not yet over for we fouled the wireless aerial as the mast went under. A man yelled out that we were making water fast and that he could not find the plug. I gave him my cap to stop it a little, but just afterwards, he found it and got it into the hole. We had about 83 people in the boat and were down to the edge. After two hours of rowing, a fishing boat picked us up but in the meantime one poor fellow who we pulled out of the water, died. After another hour and a half, a paddle steamer took us on board and we arrived at Queenstown after seven hours, so numbed with cold and wet we could hardly move. We were mighty glad to get a piece of solid ground under our feet once more.

“The happiest moment was at the hotel when the very first fellow we set eyes on was my wife’s brother. His [Fred Bailey’s] adventures were worse than ours for he went down with the ship with hundreds of others. He was clinging to an overturned boat for three hours before being picked up by a destroyer.”

(Unfortunately, no one asked Fred Bailey to tell his own story. He was born in Bridgwater c1874. His and Agnes Veals’ father Charles Bailey was an itinerant bicycle maker, all of whose children, by two wives, were born in a different English town. In 1901 Fred was a commercial clerk aged 27, his name written on the census entry at the bottom of the family list as if he was a visitor who had just dropped in. His half-sister Agnes was then 14. Fred sailed to New York in 1912. He married Mildred Moxley in Bristol in 1927, at the age of 54. This is the sum of all I could find out about him.)

(Unfortunately, no one asked Fred Bailey to tell his own story. He was born in Bridgwater c1874. His and Agnes Veals’ father Charles Bailey was an itinerant bicycle maker, all of whose children, by two wives, were born in a different English town. In 1901 Fred was a commercial clerk aged 27, his name written on the census entry at the bottom of the family list as if he was a visitor who had just dropped in. His half-sister Agnes was then 14. Fred sailed to New York in 1912. He married Mildred Moxley in Bristol in 1927, at the age of 54. This is the sum of all I could find out about him.)

Bert Veals as he appeared in the 1939 paper, almost unrecognisable from the previous photo. Bert married three times. After the death of Agnes Maud in 1924, he married Ivy Emily Mulford, 1925. She died in 1929. He married thirdly, Mabel Ellicott in 1930.

Another survivor, Clifford Ashman was the son of Henry Ashman, of Beacon Farm, Shepton Mallet. He was coming home in the Lusitania to help his father on the farm in the absence of his brother, who was serving at the front with the North Somerset Yeomanry. Clifford Ashman was not a Bristolian but shared the homecoming train with the other Bristol bound survivors as far as Temple Meads before taking a local train to Shepton Mallet. This is not the only reason he has found a place in this blog.

Ashman said he knew of passengers who received letters from home telling them of the German warning, but these were torn up or otherwise ignored.

The trip had been enjoyable but otherwise unmemorable. (He was already a veteran of several long sea voyages.) On 7 May they ran into a belt of fog which had cleared by lunchtime when he went to his cabin to lie down. For comfort he changed into an old pair of trousers and shirt, and began to read. As soon as he heard the first explosion he went to an upper deck to investigate and discovered the vessel had been torpedoed. There was pandemonium on deck with the stewards fixing lifebelts on to passengers, because many of them, having had no instructions, put them on upside down. Everybody seemed to be trying to do their best for the women and children; he saw one woman with six kids. One man appeared demented, rushing around with five lifebelts, none of which he would part with. He may have been looking for relatives who who he could not find in the confusion. Those in the saloons had a worse chance, as the lifebelts were in the sleeping compartments and many were too frightened to go below. Others, especially the 1st & 2nd Class passengers were convinced the vessel would not sink. The fiirst boat he saw launched was shattered to matchwood. The ship settled down rapidly but then began to list. When the list became more pronounced Ashman jumped overboard and began swimming “for all I was worth to get clear before the mast and funnel could strike me.” He had not set his watch to ship’s time, and saw it was 2.32 p.m. when he hit the water. He did not see the ship go down, though he felt it through the suction of the waves which he was able to avoid. A number of boats had gone down with the ship. Those that had been cut loose returned to the surface, many of them upside down. He made for one which had righted itself; he was the first to clamber aboard which enabled him to assist others to get in. Some of them were smothered with soot and dirt from the funnels.

“A few other men could swim, but not more than about one in four or five. Those who could swim did not hesitate to plunge in. They succeeded in rescuing two ladies who were floating close by. Others who appeared to be too dangerous [sic] gripping at their rescuers, but were saved by passing out oars for them to grasp. Two or three boats were in some cases lashed together and in this way assisted in the work of rescue. Some of the poor fellows were in a terrible plight from injuries received clinging to the bottom of upturned boats. One young fellow who could swim had his legs torn and skinned. Another had his clothes torn off him and was badly cut and scraped. These two were holding up a woman between them by her hair the best way they could as they clung to the wreckage. They had had a terrible time. The woman was dead when they were picked up about half an hour later by the Indian Empire.”

“Several of those on board were young men coming over to England to visit friends and intended to join the army. I figure they picked us up about 6 o’clock and we got into Queenstown somewhere between 10 and 11 p.m. The telegram I sent home as soon as I got ashore is timed to be sent out at 1:30 am, but I landed very much before that, I am sure. Amongst the persons we pulled out was a young lady, quite dead. She was a saloon passenger as she had a large number of very valuable rings on her fingers and her clothing was of the very best. Several of the boats seemed to have capsized. Among the men in one of the boats was a doctor, and his services were very valuable in saving some of the lives of those who were almost gone. He knew how to pump the water out of them and the air in.

“In one remarkable incident on the boat, a lady asked them to sing something to keep their spirits up. A clergyman started one or two hymns and they also sang “Tipperary” then went back to hymns, but this was too much. The singing had to be stopped on account of some of the women being in such an excited state. They also cheered and shouted ‘Are we down-hearted?’ – ‘No!’”

“The weather at the time of the disaster was beautiful. The sea was calm and motionless which gave many people a better chance of rescue and also assisted those who could swim. In my experience of a good many voyages, long and short, I jave never known such beautiful weather.”

In a separate item, the same newspaper printed the following pithy comment:

After an adventurous youth, in 1915, Cliff Ashman, then 27, acclimatised to life on Beacon Farm in the Mendip Hills, which he seems to have inherited and in 1921 was a dairy farmer, living there with his wife Mary Louisa, nee Tilke, and their son, Louis, aged two. They went on to have adaughter, Yvonne. What happened between 1921 and the next sighting in 1939 when citizens were required to register for war service in unknown. Cliff was then “a hand compressor operator, heavy work”, living at Dursley with Mary and their two almost adult children. His death as ‘Henry Clifford Ashman’ was registered at Thornbury in 1968.

The Ashmans were one of the foremost mining families on Mendip, and with my passion for the subject, it is not totally surprising that I recognised the surname when writing this blog. However, that is not the main reason I opened my eyes wide when I saw the report of Clifford’s escape from drowning. After sojourns in several parts of Australia doing farm work, then going to Canada, he went to the USA where he is alleged to have “settled down as a copper miner at Butte, in Montana, in charge of the magazine and explosives under ground, handing them out to the men charging and firing the shots, and supervising them where necessary.” Despite this embroidery, he was not at Butte long, but it was the coincidence of the place itself which interested me.

We went to the Lusitania Memorial on the first day of our “Great Atlantic Way Adventure.” Months later I decided it was time for a blog and high time that our Bristol Lusitania survivors had a new hour in the sun. Suddenly, I came upon Cliff Ashman. When I saw he was travelling home from working at Butte City, Montana, I almost fell off my typist’s swivel chair. Who could have guessed at a connection, albeit tenuous, between Day 1, the Lusitania, and the third day of our journey. Watch this Space.

NOTES:

The Bristol Survivors, taken from https://www.rmslusitania.info/people/lusitania-survivors/

Mrs A.E. (Gertrude) Adams, 25, nee Pollett, 2nd Class

Mr Henry Clifford Ashman, 27, 3rd Class, no additional information

Frederick Richard Bailey, brother of Mrs Veals, 40, 3rd Class, swamped boat, minesweeper

Henry George Burgess, 37, saloon, (no additional information, but presumably the same as Charles E. Lauriat, see above)

Mrs Sarah Mary Fish, age not given, nee Rogers, 2nd Class, boat, collapsible

Miss Marion Enid Fish, 8, 2nd Class, boat, collapsible

Miss Sadie Eileen Fish, 10, collapsible

Edward Harris Lander, 32, 2nd Class, “7”? collapsible

Miss Elizabeth Rogers, no age given, sister of Mrs Fish, LB 7, collapsible, Bluebell

Albert Edward (Bert) Veals, 31, 3rd Class, LB 15, Wanderer, Peel,

Mrs Agnes Maud Veals, his wife, 3rd Class, LB 15, Wanderer, Peel

Other survivors named in the text:

Charles Emilius Lauriat, junior, (40, saloon, USA, collapsible, Wanderer, Peel 12, Flying Fish) the American “captain” of Henry Burgess’s boat, a well known Boston bookseller, he frequently crossed the Atlantic making regular trips to Bath. In 1925 he spent Easter with Mr George Baynton of 1 Sydney Place, when he presented an autographed copy of his book, “The Lusitania’s last voyage” to his friend George Gregory. “He made a point of visiting the chief literary centres in England.” (Bath Chronicle, 18.4.1925)

Margaret Haig Thomas, Lady Mackworth, in 1915

Robert Leith, radio operator, joined the Marconi Marine Communications Company in 1906 and joined the Lusitania in April 1915. He received the Admiralty warnings and continued to transmit SOS messages until the final moments. Thankfully, he was among the survivors, and in 1928 when the MN Memorial was unveiled, he was chosen to represent the wireless operators lost in the War. The key to the radio room which he put in his pocket is now at the Liverpool Maritime Museum.

David Alfred Thomas, (59, Saloon, Wanderer, Peel 12, Flying Fish): Liberal politician, and Welsh coal magnate, MP for Merthyr Tydfil, later Lord Rhondda. He was so famous that a local paper’s headline, 1915, reads “Disaster at Sea, D.A. saved.”

His daughter Margaret Thomas, Lady Mackworth, aged 32, was travelling with D.A. and was rescued by the same boat. In 1923 she and Lord Mackworth were divorced. She later inherited her father’s title, becoming Lady Rhondda, but women at that time were not allowed to take their seat in the House of Lords.

Notes & sources:

This aerial view of the Lusitania Memorial Garden (title pic) is reproduced by courtesy of Creative Commons, CCO license. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:RMS_Lusitania with thanks.

[1] The de facto captain may have been Charles E. Lauriat – see the survivor Henry George Burgess, below

[2] If like me, you thought this was a modern word, it has been around since the 1600s. By the 18th century it had come to mean “Harmless teasing,” (“Penguin Dictionary of Historical Slang”, Eric Partridge.)

[3] Robert Leith the radio operator was saved. See above, “Other survivors”.

The Bristol survivors’ tales are abridged from reports in the Western Daily Press 10, 11, & 17 May 1915, & Shepton Mallet Journal, 14 May 1915; other papers, as noted in the text. I am grateful to the unnamed “newspaper hacks”, of 1915, none of whom were given a by-line, who took down the survivors’ words laboriously by hand and presented them to the world in such graphic details.

For numerous other people called Ashman, see “Killed in a Coalpit – the Lives of the Somerset colliers”, D.P. Lindegaard.

If anyone knows of other survivors, or indeed Bristol fatalities, who were on the Lusitania, please let me know.

With sheer indulgence I seize any opportunity to remember my dear dad, Jack Pillinger, born 1902. When I started tracing my own family name more years ago than I care to count, Dad racked his brains when I asked him to tell me the date his grandfather died. After a minute of thought, he said “It was about the same time as the Titanic …..or was it the Lusitania?” Before such aids were at our fingertips, I was then able to find Tom Pillinger without ado. It was the Lusitania. Our little lives are punctuated by great world events, just as my own generation recalls the death of Kennedy.

POSTSCRIPT. Before we move on to pastures new, is there anyone else as facetious as me who has noticed the appropriate names of two of the Bristol survivors, Mr Lander and Mrs Fish?

———————————————oOOOo——————————————–

To continue with the first day, we went to sundry ruins, often monastic, but who knows? There are too many to have history boards…. (by the way, who says it always rains in Ireland?) ………..

To continue with the first day, we went to sundry ruins, often monastic, but who knows? There are too many to have history boards…. (by the way, who says it always rains in Ireland?) ………..

……and continuing onward……..

……. By chance we spotted a windblown wood “sculpture” which was the spitting image of our old dog, Patch, a lab/cross rescue, with a white bib, sticky-up collie ears, and a lisp – Oof! – who is sadly no longer with us.

……. By chance we spotted a windblown wood “sculpture” which was the spitting image of our old dog, Patch, a lab/cross rescue, with a white bib, sticky-up collie ears, and a lisp – Oof! – who is sadly no longer with us.

I am avid fan of monoliths, Obelix the Menhir Carrier is one of my literary alter egos; I go to the Standing Stones of Stanton Drew, at least once a year.……..

…….so, it was off to the unmissable and more sophisticated Drombeg Stone Circle…….

………where Kevin and his dad, George, shared a joke, probably about their pre-historic Bronze Age, hunter-gatherer forebears…….. or maybe not…..

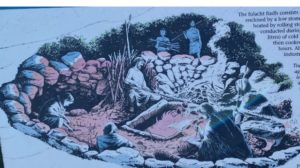

……. but the ancestors were definitely cooks (Chefs!) whose cooking pit fulacht fiadh survives. The pit would have been full of water, into which were rolled hot stones from the hearth for cooking meat. Good news! It made raw carcases more digestible. There was also a roasting facility excavated nearby. From so long ago it is difficult suggest the exact progression of new ideas.

Think about it.

Think about it.

In the next 1000 years or so, there comes along some Clever Dick who invents the next Big Thing which is the latest “Must Have”, (dead easy to operate), and where everybody goes for the Saturday night cook-out.

The elders do not understand how to use this newfangled thing. And secretly go on rolling stones. The youngsters mutter “Quicker to train a Chimp.”

Experiments at the fulacht fiadh, (1935) by Prof Fahy, demonstrated that 70 gallons of water could be heated in the trough by adding stones that were glowing after baking three hours in the hearth. Eighteen minutes later, the water was boiling vigorously, and it remained hot two hours later.

“Six years later Professor Michael O’Kelly and his students took the experiment further……Using a 10 lb (4.5 kg) leg of mutton, O’Kelly tied it inside a bundle of straw to keep out the muddy grit from the water. He then lowered the bundle of meat into the boiling water and when it had sunk below the surface put in extra stones every few minutes in different parts of the trough which was kept simmering rather than boiling. This continued for three hours and 40 minutes, the time based on the modern recipe of 20 minutes to the pound plus 20 minutes more for each pound of meat. The surface of the water was covered by a scum, globules of fat mixed with ashes and fragments of charcoal, which had gone in with the hot stones. The water itself had become opaque because of the churned-up mud from the bottom.

“We wondered if the meat would be edible but when taken out at the end of the stated time and removed from its covering of straw it was cooked through to the bone and to be free of all contamination.

“Thus, we satisfied ourselves that such a trough made in the ground could be used effectively for the cooking of meat in the method described in early Irish literature.”

This account is taken from https://voicesfromthedawn.com/drombeg-stone-circle/

They didn’t say whether anybody tasted the mutton!

And so, on to Skibbereen and Day 2…..

Leave a Comment