“By Ros, Car, Lan, Tre, Pol and Pen shall ye know Cornishmen”. (Survey of Cornwall, Richard Carew, 1602)

The white walls and plain, utilitarian lines, (none the worse for that), tell a tale.

In a previous incarnation the Mining Museum was a Wesleyan Chapel, built by/for the non-conformist engineers and skilled miners imported from Cornwall to run the Allihies/Berehaven mines. Legend even has it that it was a Cornish Dragoon lieutenant, out on patrol in the wild and rugged hills thereabouts who spotted the potential of a stream of metal spilling out from the ground. The Mining operation began in the early 19th century. In the time machine of my mind, I was about six again, trotting off to Sunday School in Kingswood.

As usual with my tendency to get carried away, I have now collected enough information for a book, but don’t worry, most of this stuff will not be aired here and now; neither will this blog be a tour of the Museum but confined to three favoured items. You have probably guessed already that my first love, among the many others of subsequent vintage, were my ancestral colliers, so I embraced the Allihies miners as my own, even if they mined copper, and not coal; long-lost historical cousins from a different branch of the family.

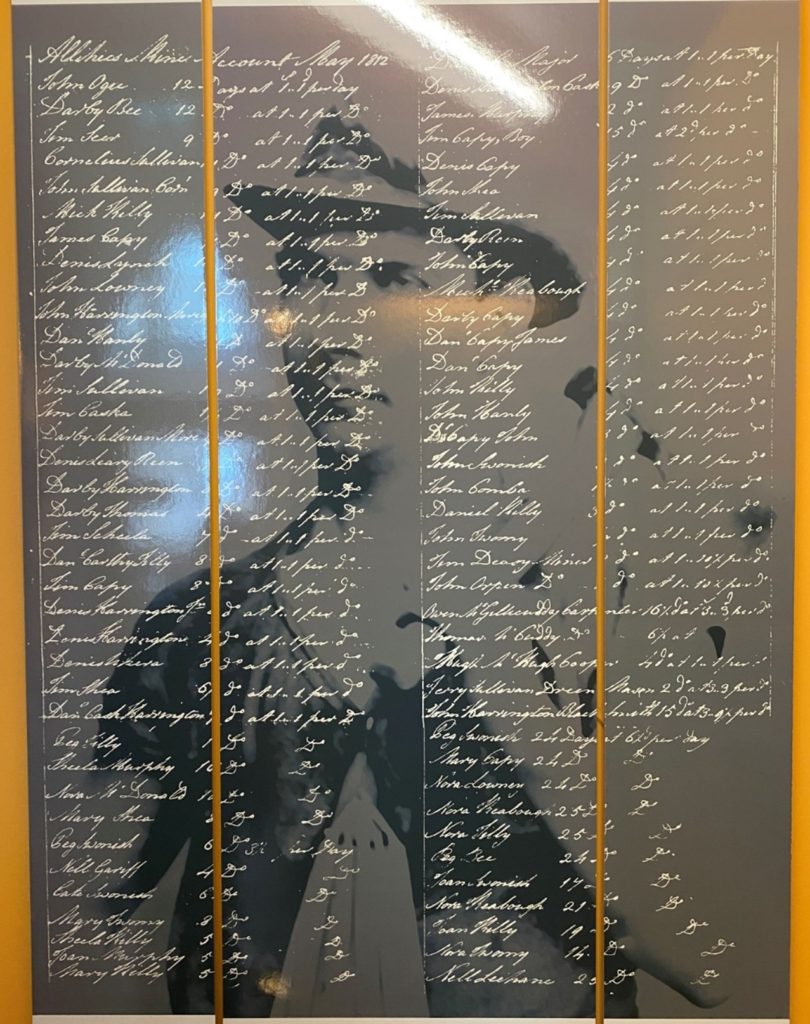

I suspect most visitors would pass by my first object pretty quickly: a handwritten, hard to read, tally of workers from 1812, the year the Allihies Mining Company began, locally known as Puxley’s Mines, after the principal shareholder, John Lavallin Puxley, 1772-1856, known as “Copper John”.

(The Puxley family, whose roots in Ireland go back to the 17th century, were landed gentry belonging to the class known as “Anglo-Irish”, a group who were generally better off, spoke English and were Protestant. The Puxleys sent their sons to Eton and Oxford; the heir inherited, and the spares joined the Army or were ordained into the Church of England. It pleased me no end to find, unexpectedly, that Copper John’s grandson and namesake lived in Bristol for a time, with four of his children baptised at Clifton 1831-35. In the census of 1841, the eldest aged 10, “born Ireland” was at Mortimer House, a boys’ boarding school, with the others aged 7, 5, 4, at Wellington Hill, in the care of three female servants but with no sign of their parents, which is a worry for another day.)

Cornwall was the acknowledged centre of metal mining expertise. The first “Captain”, of the twenty-seven skilled Cornish miners who began the operation was John R. Reed; he ran the mines for more than a quarter of a century, and was succeeded by his son and namesake, who was the boss for the next twenty-five years. Somebody must know who the original “27” were but unfortunately, I don’t; my list, from May 1812, is longer, and names local Irish people, men and women, paid by the days worked; irregular toil, possibly comparable to the infamous zero-hours contract regrettably still with us today.

“1s 1d” seems “nice work if you could get it”, as is the 6d per day paid to the women, which is a better rate than females enjoyed in 1841.

Only two people on the list are specifically “miners”, John Deavy and John Orpen; possibly not from the regular skilled men, but “Cousin Jacks” who turned up on spec. They were paid 1s 10d per day. The other rates suggest urgency to get the job done. These artisans were Owen M’Gillicuddy, carpenter, 3s 3d, Thomas M’Cuddy, probably his boy, 6d, Hugh M’Hugh, cooper, 1s 4d a day, John Harrington, blacksmith, 3s 9d per day, for 15 days, & Jerry Sullivan Dreen, a mason, 3s 3d, per day for two days.

The list is an amazing survivor, and I have noted all the men, Christian and surname, elsewhere for a future blog. It is exceptionally rare though for women and girls to be named, so here they are, in the order they appear:

The list is an amazing survivor, and I have noted all the men, Christian and surname, elsewhere for a future blog. It is exceptionally rare though for women and girls to be named, so here they are, in the order they appear:

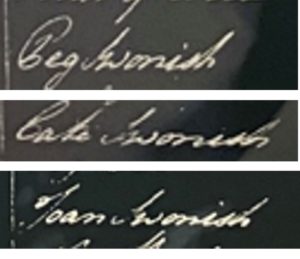

Peg Tilly, Sheila Murphy, Nora M’Donald, Mary Shea, Peg Kvornish*, Nell Gariff

Cate Kvornish, Mary Twomey, Sheila Reilly, Peg Kvornish (twice), Mary Copy,

Nora Lowney, Nora Keaborough, Nora Tilly, Peg Bee, Joan Kvornish, Joan Reilly, Nora Twomey, Meg Lehane.

If you can decipher the surnames, please let me know.

I stared at the list in its glass case, mesmerised to see women at all, and then more excited by three of the names, because I thought I had discovered a family of Cornish women, speaking their own dialect with rolling RRs and flattened AAs as one born in the English West Country would do. But I really don’t know, and I don’t know why they would be there. The skilled Cornish men would be “a cut above” and surely would feel demeaned if their women did this type of work, washing the ore as it came up from the mine. None of the men on the list have similar looking surnames. Something which came of it is a separate line of inquiry, a new index for me, of “Bal Maidens” (as the true Cornish called them, which as I found, did mining work all over the British Isles.) If poor men are often ignored by history, then the majority of women hardly exist at all except, like these ones on the right, through layers of a glass darkly.

I expected a trawl of newspapers would help me bridge a gap between 1812 and my next chosen item but without too much success. The press was more interested in the nobs, or business, mining yields and dividends. In this remote area, it is unlikely that anyone was on hand to relay the doings of the poor. I seized the scraps I found about “the middling sort”, from which I gathered Captain Reed was called John, with wedding announcements enough to prove that he and his family were Wesleyans and connected to Cornwall. Additionally, a turnover of three mine surgeons raised the grisly thought that sometimes amputations were necessary on site, but there were no details, other than that one of the surgeons had been thrown from his horse and accidentally killed, a fate shared on a separate occasion by a local Wesleyan minister. Horse riding over the wild terrain was a necessary but dangerous business.

Salvation came with the Government Enquiry, published 1842, concerning the “Conditions of Children and Young Persons in the Mines and Factories of the British Isles,” which included Ireland. Frederick Roper, a Dublin man was sent to investigate, and Allihies was on his list. I confess to surprise that there were so many mines in Ireland!

(The Enquiry, “Children in the Mines & Collieries of South Ireland” has been posted online, https://www.cmhrc.co.uk/cms/document/1842_Ireland.pdf

by the incomparable Ian Winstanley of the Coal Mining History Resource Centre, to whom I owe my sincere thanks once again.

Mr Roper’s report, here abridged, notes “the isolated and desolate area”, where Irish was the only language of the majority. He could not have communicated with them without an interpreter. They rarely went farther afield than Castletown, about six miles away. They were poorly clad, and seldom ate more than two meals a day, consisting of potatoes and, occasionally, a little milk. Despite this limited diet, old and young looked healthy, and did not appear underfed. A resident doctor was paid for by the company. Only the children of the mechanics and the better class of miners went to the day school. A Wesleyan preacher attended on Sundays, but most people were Roman Catholics, with a chapel about two miles away. They were usually entirely uneducated, illiterate, and most children had never been to school; the parents said it was all they could do to provide food for their families. Some of the miners lived better but most could barely exist.”

These were the individuals interviewed:

Captain Reed, – all the mine bosses were called “Captain – by 1841 he had been in the job at Allihies for 26 years. He kept the mines in excellent order. There were very few children working there. Captain Reed did not like taking them young. He said, “They are more trouble than they are worth.” Six workers were interviewed out of 800 employees there.

Joan Tobin, aged about 30, was unmarried, had worked at the mine 18 years and lived about 2 miles away. Worked at “picking” but was usually “budling”, washing the ore. She was paid 4d a day and had never been paid more than 4d-5d in all her years. She said her health was good. She came to work “at six in the morning as the bell rings and leave off at six in the evening when the bell rings again.” She had half an hour for breakfast and an hour for dinner, which was the same for the rest of the women and girls. Many only had one meal a day, but she had supper at home after finishing work. She lived “mainly on potatoes, sometimes milk and sometimes a bit of fish.” She worked for a contractor, as did most of the budlers. He paid her regularly. “I never had any complaints to make on his head. I like my work very well – it is none of it very hard work.”

Cornelius Kelly was 15, lived with his parents close to the works. Had worked there four years. “Today I am wheeling stuff to the budlers. Some days I am working at the jigging – I like jigging the best of all the work. I get 6d. a day for my work. I always get my wages quite regularly every month. I am well treated in the works. My meals are sometimes brought to me and sometimes I go home for them. I take my wages to my mother. I do not now go to school. I can read and write a little. I go to chapel on Sundays. I had 4d. a day when I began to work.”

John Frewhella, sic, aged 11. (My comment: This clearly should be Trewhella, lost in translation or transcription. He might just as well have hung a sign round his neck. The surname is 100% Cornish.)

He lived with his mother and had started work 14 months before. He was now paid 5d a day blowing the bellows for the blacksmith. A Captain paid his wages which he carried home to his mother. He found the work hard and very hot. He was in good health and said he always had been. He could read and write. “I read the Bible on Sundays. I go to Sunday School for an hour and learn my catechism.” (He was undoubtedly Wesleyan. His inclusion may suggest that not all the Cornishmen had gone on to success, but he was clearly a bright lad.)

Mary Reen, aged 18, “lived with her mother, close by here”, sometimes had her dinner when she went home. Had been at work for five years. “I am today working at trunking, which is one of the washings – I have generally worked at trunking; sometimes I wheel stuff to the budlers. I get 4d. a-day now – I never had more than 4 or 5d. My work agrees very well with me. I have never stopped a day from sickness. I cannot read or write. I have been but very little time indeed at school. I can sew a little but not much. I don’t think I get enough wages, but I get as much as the others.”

Catherine Leahy, 16, lived nearby with her parents. In good health. Had worked four years, always at trunking. “I only get two meals a day. Many of us do the same. I have never been to school. I can neither read nor write. I can sew a little but very little. We make but very little difference between our clothes winter and summer. I have some better clothes that I keep for Sundays. I like my work very well. It is not very hard work.”

Philip Donovan also 16, lived with his parents close by. “I have been five years in these works. I am wheeling to-day, but generally I am at work jigging. I get 6d. a-day. I go home to my meals. I get paid very regularly. I have no complaints to make about that. I can read and write a little. I take my wages to my mother; I like coming to work here very well. I have never worked at any other kind of work.”

The people’s statements are so similar, so bland, that someone even less suspicious than I am, might think they had been rehearsed. I believe the situation was much as I encountered when researching KIACP for Somerset, i.e. the foreman was in the room with them and listened in to their replies. Nobody gave a whisper of ill-treatment. The work was not hard. The workers were as happy as Larry. Only Mary Reen was brave enough to suggest she was not paid enough……..

A jaunty little chap – in the wet – happy in his work?

The report may suffer from Mr Roper’s inability to speak or understand Irish. Perhaps he was struggling to think of something to say from the information relayed by the interpreter. It could be that the three boys who were literate were deliberately chosen because it was easier to understand them. The people’s diet consisted almost wholly of potatoes, despite which they “looked healthy”. Having been to Skibbereen the previous day it was impossible for me not to remember that in a scant five years the same people would starve when the potato crop failed.

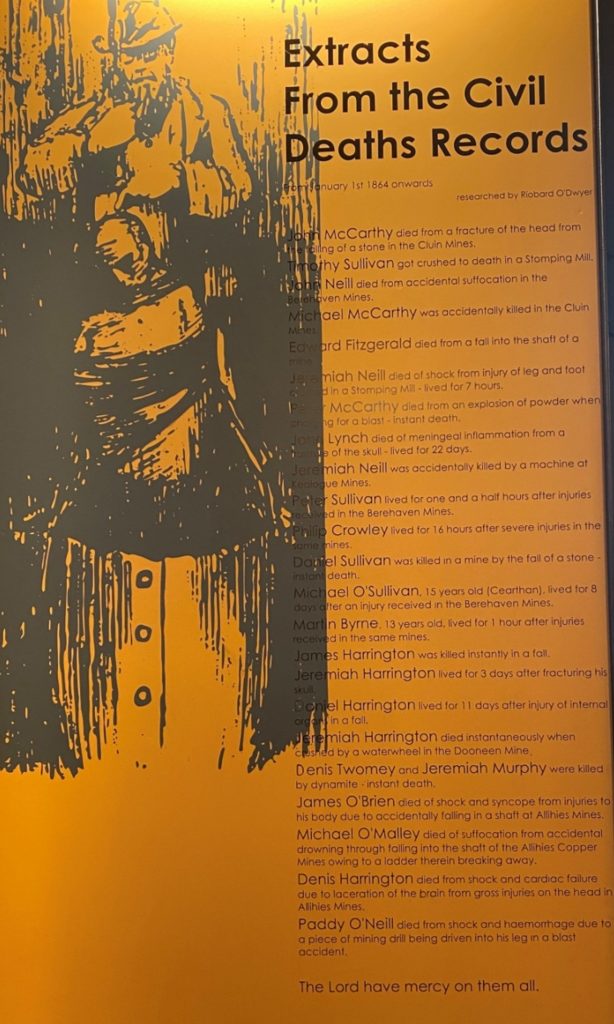

My second item is another list.

Though newspapers were published from the 1700s, they contain few local events. Mining was dangerous, accidents were common, and death was an occupational hazard. It happened to poor people and often went unreported. “Killed in a Coalpit” the title I chose for my books was not meant to be morose but to reflect that the manner of his death might be the only information known about an individual miner. A tedious search through the small print is always required but can be rewarded.

The list of Allihies/Berehaven fatalities, extracts taken from the Civil Registration Indexes (which began in Ireland in 1864), displayed in the Allihies Museum is therefore greatly welcomed, but I find it hard to believe that the scribe left out the vital information of dates! It doesn’t help either that some information of the script on display is obscured by a pen & ink drawing:

John McCarthy, died from the fall of a stone in the Cluin Mines

Timothy Sullivan crushed to death in a stomping mill

John Neill suffocated in the Berehaven Mines

Michael McCarthy, crushed in the Cluin Mines

Edward Fitzgerald, fell down the shaft

Jeremiah Neill, died after 7 hours from shock after injury to leg at stomping mill

Richard McCarthy, explosion of powder died instantly

John Lynch died from fracture of skull after 22 days

Jeremiah Neill, killed by a machine at Killalogue

Jeremiah Neill, killed by a machine at Killalogue

Peter Sullivan, lived 1½ hours after injury in Berehaven

Philip Crowley, lived for 16 hours after injury at Berehaven

Daniel Sullivan killed by fall of stone

Michael O’Sullivan, 15, lived eight hours after injury Berehaven

Martin Byrne, 13, lived one hour after injury at Berehaven

James Harrington, killed in a fall

Jeremiah Harrington, lived 3 days after skull fracture

Daniel Harrington, lived 11 days, internal injuries

Jeremiah Harrington, killed by a water wheel

Denis Twomey & Jeremiah Murphy, explosion of dynamite

Mihael O’Malley, fall due to breaking of a ladder

James O’Brien, drowned when fell into a shaft due to breaking of a ladder at Allihies

Denis Harrington, laceration of the brain, Allihies, died of cardiac failure

Paddy O’Neill, shock and haemorrhage due after piece of mining drill driven accidentally into his leg.

I have also found three more:

Mr John Reed, (Cork Examiner, 26.7.1861), probably the junior version, speaking about a strike in the Berehaven Mines denied it concerned wages, but was owing to working conditions: “the discovery of unsound killas (sic) ground in the main workings where one fatal accident had occurred and deterred the men from continuing work. Precautions had been taken, and the men had resumed their contracts.”

The next is from the website https:aceh.ie/local-history but is otherwise unsourced and minus the year: “A Mine Captain reports on the 13th inst. we had a man killed by falling out of the whim bucket in the whim shaft (winding shaft). He fell 72 feet and was killed immediately. The whim bucket was coming up and he was rather late to get into it when he laid hold of the edge of it with his fingers, was drawn up nearly to the top in that manner but was obliged to let go at last and fell to the bottom of the shaft. He was very able young man. This day we intended to carry him across the mountain to Castletown, seven miles, to have him interred but the weather is so bad with the fall of sleet and snow that it was not possible. We hope to do the last rites for him tomorrow.”

Neither of these fatalities is named.

Neither of these fatalities is named.

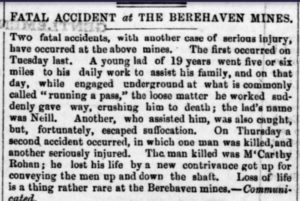

A report in the Cork Examiner, 16.10.1865 is more helpful:

Nineteen-year-old Neill, who was crushed to death may be the John Neill on the list who “suffocated in the Berehaven Mines”. Michael McCarthy, who met another dismal end, could be the same as M’Carthy Rohan, immediately below Neill in the list. However, the cutting offers another useful item of information.

The “new contrivance got up for conveying the men up and down the shaft” must be The Man Engine, which housed one of the most iconic features of the Allihies landscape, and towers like a fortress over the village. My third object for consideration.

To be continued…….

Leave a Comment