I refer you back to the teasing trailer elsewhere on this blog called “If there is a hole dug anywhere on earth, you’re sure to find a Cornishman at the Bottom”.

At Allihies, the notice board, (from Beara Tourisme), translates ‘Mountain Mine’ as ‘Minach Mór’.

“Mountain Mine, (Minach Mór), copper vein was discovered in 1813 and began as an opencast mine following the copper bearing quartz vein as evidenced by the huge gaping holes on the site. The miners attacked the hard quartz with hammer, chisel and gunpowder. In the early years it was completely reliant on manpower. Buckets with ore were manhandled from the depths and hand crushing and sorting took place at the surface, beside the open cast mine, a laborious process undertaken mostly by women and children. Evidence of the discards can be seen in the rubble all around. The first Engine House was erected in 1830, (the North Engine), which pumped water from underground to enable deeper mining. The Engine Houses were the key to the success of the vast enterprise and housed the magnificent steam engines developed in Wales and Cornwall to serve the mining industry all over the world. The largest, the Man Engine House was erected in 1862 to lower and lift the miners up and down the shaft. It is unique, being the only Man Engine House in Ireland, and one of only a few surviving in the world. (Vital conservation work by the Mining Heritage Trust of Ireland took place in 2004.) The Mountain Mine was the most productive in the Allihies complex and was in continuous production from 1813 until closure in 1882 by which time it had reached a depth of 421 metres, 280 metres of which were below sea level.”

I would like to say the penny dropped immediately, but there was too much going on in the moment for me to make the connection between two remarkably similar words, but with me there is often a self-indulgent ramble, and for this one, I take myself back to the summer of 1967.

I was on the way to a holiday in the Scilly Isles with my friend Judy Elles, one of the many people in my life who have gone on before me.

Photo courtesy (Copyright) https://archive.questors.org.uk/prods/1967/phaedra/gallery.html.

Minack, (one consonant away from Minach), is the spectacular open-air theatre overlooking the sea, high in the rocks outside St Ives, and was on our route. Of the pair of us, at the time, Judy was the arts buff, I was less the finished article. She had been before, said it was an opportunity not to be missed, and booked our tickets. Patrons sit in an amphitheatre on stone benches hewn from the virgin rock and though still bathed in brilliant summer light, the evening was bitingly cold. In 1967 if you wanted blistering heat you went to Lloret de Mar, not Cornwall. I longed for an air cushion, a heavier coat, a hot drink and my lover back home in Bristol. (“Reader, I married him” – Charlotte Bronte – “Jane Eyre”) What little memory I retain of the play before today suggested Shakespeare, but the archives, which don’t lie, say it would have been Phaedra by Racine, all forbidden love, guilt, shame, lies, revenge and suicide. Do not go expecting A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum, unless this is what the programme advertises. The Minack Theatre is magical for all that, and every theatregoer should go there at least once. But do take a coat, a cushion and a hot drink/date. [1]

On the morning of Day 3 we left the Pods grumpily without tea and toast, not even a biscuit. Our travelling itinerary did not allow time for shopping. The more optimistic of us, (Algernon, our tour guide) said we were “bound to find a coffee shop on the road”, but did we heck? This happened several times at different places; even in hotels you could usually get dinner but often they did not serve breakfast. This was not something we had encountered in the rest of Ireland, only in the remote west. A greasy sausage roll helped George along the way at one point, but as an insult to injury, it came not in a paper bag, but in a Perspex box, twice its size. Environment. What environment?

Our first call of the day proper was Ballaghboy on the tip of the Beara Peninsula, to take the ten-minute trip to Dursey Island, Ireland’s only cable car, which has the additional distinction in all of Europe of being the only one which crosses the open sea ..…..

……250 metres high in the air. Before the Cable Car (1969) the only way across the treacherous Dursey Sound was by rowing boat….

On our April morning, Beara Sound was calm….

We expected to encounter more people; but here we are, in a cable car made for three, – capacity six persons.

…….. George looks apprehensive, but this is his “loving it” face. (photo: Brutus Tours ©)

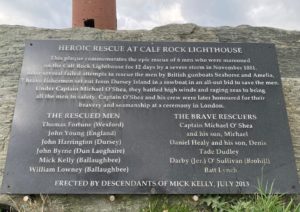

Rush Hour on Dursey Island. The building in the distance is the Calf Rock Lighthouse, an islet off the mainland of Dursey, the scene of tragedy in 1869 when there were multiple fatalities, but in 1881 there was a happier outcome when six men who were marooned there for 12 days were rescued by local fishermen, battling high winds and raging seas. Kevin, who climbed to the top for bird watching purposes took this photo of a memorial plaque, to a young man, a member of the Cork Samba Band………

Rush Hour on Dursey Island. The building in the distance is the Calf Rock Lighthouse, an islet off the mainland of Dursey, the scene of tragedy in 1869 when there were multiple fatalities, but in 1881 there was a happier outcome when six men who were marooned there for 12 days were rescued by local fishermen, battling high winds and raging seas. Kevin, who climbed to the top for bird watching purposes took this photo of a memorial plaque, to a young man, a member of the Cork Samba Band………

…….. and this one, in memory of a heroic rescue.

He became passing friends with two American women and their young daughter who were hoping to settle in Ireland. He gathered they were escaping their president. Enough said. They shared our cable car on the return journey.

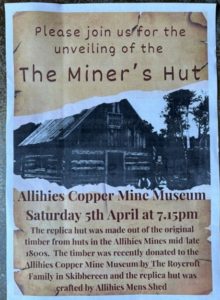

Back on terra firma we chatted with the affable cable car operator, David Dudley, and I discovered a fellow mining enthusiast. It appears that Butte, Montana, “is now largely populated by the descendants of Irish migrants”. The mass emigration from Ireland already underway would have been increased by miners, after the closure of mining operations in the 1880s, including those from the Berehaven Mines. David told us that in the Allihies Museum, our next destination, we would see a model of an “American miners’ hut” which had been crafted by himself and other members of the local Men’s Shed. [2]

Back on terra firma we chatted with the affable cable car operator, David Dudley, and I discovered a fellow mining enthusiast. It appears that Butte, Montana, “is now largely populated by the descendants of Irish migrants”. The mass emigration from Ireland already underway would have been increased by miners, after the closure of mining operations in the 1880s, including those from the Berehaven Mines. David told us that in the Allihies Museum, our next destination, we would see a model of an “American miners’ hut” which had been crafted by himself and other members of the local Men’s Shed. [2]

An hour or so later we were gazing at the table-size model which David called “an American Miner’s Hut” in the Allihies Mine Museum. Kevin and I tuned to a simultaneous thought, which was “I had expected it to be larger.” The photograph on the poster advertising the unveiling, (April 5th, 2025, only days before we came to Ireland) depicts a late 19th century mining family, in America, in front of their dwelling, about 100% more likely than the model itself, which is a highly idealised version. This is not to detract from the concept, expertise, or attention to detail of the model makers.

A little knowledge is anathema to me, so what comes next, came later. This account of the “American Miners’ Huts” at Allihies is abridged from https://allihiesmsp.github.io/ : “Sometime in the mid-1800s, the Copper Mining Co. placed an order for Nine Miners’ Huts to be shipped from USA in kit form which were reassembled on the mine site at Allihies.

A little knowledge is anathema to me, so what comes next, came later. This account of the “American Miners’ Huts” at Allihies is abridged from https://allihiesmsp.github.io/ : “Sometime in the mid-1800s, the Copper Mining Co. placed an order for Nine Miners’ Huts to be shipped from USA in kit form which were reassembled on the mine site at Allihies.

“After the mines ceased production the American style log cabins stood empty for years until the site was cleared and the equipment was bought by the firm of Wm. G. Wood and Sons. William Wood recognised the superior quality of the wood, Pitch Pine (Pinus Regida) and White Pine (Subgenus Strobus), hewn from the slow growing natural forest of North America.

“Mr Wood demolished the huts, had the timber milled into uniform size and incorporated into the new bungalow he was building outside Skibbereen in 1915. In the 1940s, the bungalow was bought by the Roycroft family of Grain Merchants, who knew the tale of the American Miners’ Huts via generations of oral history. (My italics). When the historic dwelling was itself being demolished the value of the old timber was realised and its importance of the huts’ story to shared Irish/American social history. The Allihies Mining Museum was intrigued and passed the project to the local Men’s Shed who saved what was usable of the original wood and constructed the model ‘using authentic techniques ensuring its Period Correctness based on online research.’”

Hmmm. I confess to some scepticism. “Flatpack” in the mid-19th century? It sounds too much ‘a visit to Ikea-ish’. Maybe just enough timber to make four walls and a roof sufficiently stout to keep out the weather? And built to last. Obviously. The figure of nine huts is specific enough and I assume the “American” wood was analysed. Wood was traded between the Americas and Great Britain, where it would have landed first and then been brought to Ireland in one of mine-owners ships.

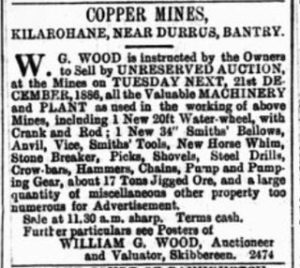

The aptly named Willliam G. Wood existed, and auctioned mining paraphernalia. per this advertisement, in the Cork Constitution 16.12.1886.

The aptly named Willliam G. Wood existed, and auctioned mining paraphernalia. per this advertisement, in the Cork Constitution 16.12.1886.

A William B. Roycroft was also an auctioneer in Bantry, at least 1904-17, perhaps just a coincidence?

The story sounded more gristle than meat, and I searched in vain for anything documented to prove the actual existence of the huts: a picture, a bill of sale, would have been nice. There are just too many gaps: “mid-19th century”, then thirty odd years between then and the 1880s, which saw the clearance of the mine site, and 1915 when Mr Wood used the wood to build his bungalow, with another thirty again until it was demolished by the Roycrofts. Plenty of time for embroidery, but not much to go on.

I didn’t know quite what to make of it. To be honest, I doubted the huts ever existed. I know, I know. I am a mean and horrible person, who does not believe in Father Christmas, but I could not leave it hanging. This was before I heard the name “Puxley”. (see Day 3, part 2)

An area of the Allihies landscape is called “Hungry Hill” which is also the title of a lesser-known work by Daphne du Maurier. I had never read it, and on-line blurbs quoted disappointed devotees who expected another “Rebecca” but included the nugget (sorry) that it was a saga about a family of Irish mine owners, the “Brodricks” based on the Puxley family. Du Maurier’s love affair with Cornwall is well known. It is not surprising that she seized upon a tale, with its undertones of her adopted home, told to her by a neighbour about his Puxley ancestry and the Irish mine. When expansion and excavation was on the cards from the original Drift, the original entrepreneur, Puxley, needed to call in experts, skilled miners from Cornwall, the county of acknowledged metal mining specialists.

I was in two minds when I also discovered that du Maurier had not herself been to Ireland, but curiosity got the better of me. The library could not locate a copy, of the book so I bought one, (used, my second choice, environmentally friendly, cheaper, often with a good bargain to be had.)

Lucky for me I did so.

At the time of Puxley’s first engine house of 1830, there must already have been an influx of the Cornish engineers. The book suggests animosity between the locals and the newcomers, so Mr Puxley thought it best to separate the two factions.

“He had huts erected, at his own expense, close to the mine on Hungry Hill and fitted them up with the necessary furniture, bedding and cooking apparatus. Some of the men were married and brought their wives and children.”

This little paragraph has the ring of the original story as told to Daphne, God bless her, or else why bother to put it in?

Thus, the story was known well before 1943, the date of the book’s publication. It places it contemporary with the Roycrofts, proof, sort of, that the huts existed but not quite in the form the model suggests. They were inhabited by a strange breed of men who threatened jobs done more laboriously by local hands. I can’t imagine such people who became the mine “Captains”, who followed a different path, and built their own Wesleyan Chapel, lived longer than necessary in a place resembling a caravan site. Ergo, other uses were found for the huts. I guess that the revelation that the wood from these durable structures came from across the Atlantic gave the story new legs. A legend which allowed flatpack American log cabins to flourish.

If the novel has any more about the huts, I’ll let you know. At this moment, I’ve only got up to page 33, and it’s a doorstopper of over 500 pages. I think Daphne, judging by her vast output, wrote quicker than I can read.

At the time of my conversation with David, Butte, Montana, once a rough and tough mining town meant nothing to me. Just imagine the goose bumps when it cropped up again when I was writing the blog for Day One of our adventures and had an unexpected encounter with Cliff Ashman, farmer’s son and round the world traveller. In 1915, he was homeward bound to the Mendip Hills, not a million miles from where we live, coming from – of all places, Butte, where he had briefly worked as a miner. He had booked a passage on the RMS passenger liner Lusitania and was among those lucky enough to survive when the great ship was sunk by a German U-Boat off Cobh. The older I get the more I see all of us as miniscule pieces in the same jigsaw.

Me with David outside the cabin from which he operated the Cable Car.

Within days of our visit, David would be on his way to visit – Butte! – where the wonderfully named Orphan Girl Mine, plunged to a depth of 3200 feet, and produced silver, lead and zinc, 1875 – 1956. By the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries over a quarter of the population were Irish. There is an (allegedly) true story that an Arab rug trader named Mohammed Akara officially changed his last name to Murphy which, he claimed, was for ‘business reasons’! There were a few “Cousin Jacks” in Butte too, the usual mining casualties plus a Colonel Bray, possible civil war veteran (?), a Cornishman and successful Butte grocer, who was put up as a Republican candidate for Mayor in 1905. The town is the home of a visitor centre modestly titled The World Museum of Mining. Of course. The model has found an appropriate home.

NB: Explanation. This blog started with the notice board at the “Mountain Mine”, Allihies, translated as Minach Mór. Without going too deeply into my amateur lexicology, I suggest the phrase is a Cornish-Irish hybrid. Meynek or Minack, the scene of the incident in another time of my life, is Cornish for “Rocky Place”. Mór with the acute accent is Irish for “Big”; without the accent Mor is Cornish for “overlooking the sea”. Not quite QED but it fits my love of origins and connections. In the next chapter, there are plenty of Cornishmen and the possibility of the odd bal maiden too.

Day 3 was supposed to be a one-entry blog, which got away from me. Who has mild ADHD or what?

To be continued…… onward to Allihies.

[1] What I have read about the extraordinary Rowena Cade whose life’s work it was, she had a lot in common with Algernon, of Brutus Tours, except she had a great deal more cash to indulge her dreams.

[2] It is a detailed model . David was responsible for the project’s concept, design and was the main woodworker. https://www.facebook.com/reel/1347043439709761

Leave a Comment