Caroline said “What about the Isle of Man? I’ve always fancied going there.” We were planning a few days away, somewhere not too arduous, for around the time of my 86th birthday in June 2023. I had never given the Isle of Man any thought at all. So straightaway I asked, “Are there any mines?” I always like ‘a mine’ on my birthday. My interests are eclectic but not everybody shares them. This is hard to believe, I know, but a few people find social history and libraries, standing stones, fossil hunting, even mining, boring, and give me the rolling-eyed “whatever” look. But the answer was affirmative. “Yes!” cried our eldest child, in triumph. “The Laxey Wheel. I’ve googled it!”

The Great Laxey Wheel, the largest surviving water wheel in the world, was built in 1854 to pump water out of the Great Laxey Mine, all good stuff. A few weeks later four of us flew off to the Isle of Man, ‘George’ (real name, Norman, but we all call him George) and I, with our daughters, Caroline and Celia, minus the impedimenta of spouses or kids.

I recommend the bargain combined ticket which covers several days, all forms of transport and entry to most attractions, the Laxey Wheel included. It was a convenient and easy way of getting about to the most popular and well-known destinations especially as time was limited. We spent our first day at Laxey and our second at Snaefell, the highest summit of the island.

The picturesque village of Laxey can be easily accessed from Douglas, by one of the elegant Victorian trams, fully (historically) electric, with their mahogany seats (you may consider an inflatable cushion) and gleaming brass. In high summer the trams can be very crowded but the only time we saw other tourists in any number was during our penultimate day spent at Peel Castle, when a coach party arrived.

The Great Wheel, built in the hillside above the village, dominates the landscape. The Great Laxey Mine (which the wheel served) and the Snaefell Mine, higher up the hill formed the Isle of Man’s industrial complex along with the other collective at Foxdale which we did not have enough time to visit.[1]

We had the place almost to ourselves. Close up, the Great Laxey Wheel is even more impressive than from below. Built in 1854 during the height of the prosperity of the mine, the Wheel, otherwise, Lady Isabella, (named after the wife of the then Governor of the island, Sir Charles Hope) is the largest working water wheel in the World: 72½ feet in diameter. During its working life it could pump 250 gallons of water a minute from a depth of 200 fathoms. (370 metres).

Before we arrived, we had no idea how lucky we were to see ‘the Lady’ in action; she only returned to glory (and turned again) in the autumn of 2022, after the first phase of loving conservation was completed. The old render and rotting timbers were replaced (with commendable attention to detail) by Douglas Fir, sourced from Scotland, near as possible to the original; the ironmongery was repaired and the wheel itself, railings and viewing platform gleamed with spanking new paintwork. In the early June sunshine of 2023, Lady Isabella shone.

Ideally, please take the spiral staircase, up many steps to the top, to see the water flowing and the wheel turning, not forgetting the panoramic view of the valley below……. but George has dodgy knees, and though I can go up, (rickety, OK, if you think tortoise), and with my faulty eyesight, I am a menace descending, a danger to myself and anybody who mischances to be in the way. Our daughters did it for us by proxy. They took the photos here, but to see something of what they saw I recommend YouTube videos.[2]

Leaving the immensity of the Wheel behind us, we strolled further up the “Miners’ Trail” along which men had tramped to work from miles around. We paused to look the view with the stream twinkling over the rocks just before the mine entrance. A small case on the wall beside the adit contained examples of the various minerals the IOM mines yielded: zinc, lead, copper pyrites, haematite, even silver.

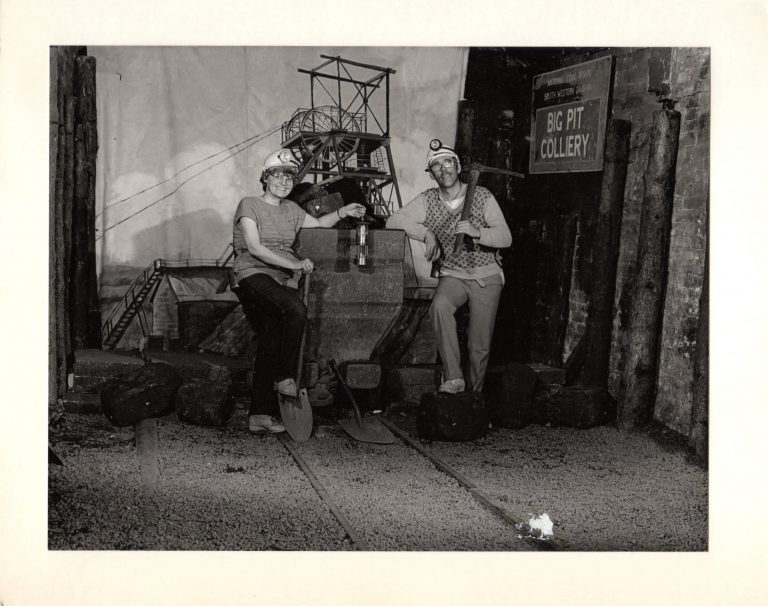

DPL & George, overlooking the stream and terrain. The entrance to the mine is just beyond.

En route we had been warned by cheery members of a cycling club who were on the way down “don’t expect to see much inside” but in view of the issue of hard hats we were more optimistic, though to be honest, they were correct.

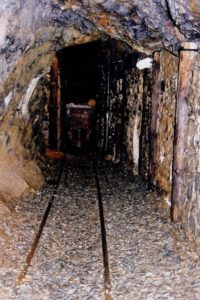

A few yards in and that’s it. Just a tunnel to a blocked wall. Don’t be fooled by the man filmed in the YouTube video. He makes it look a much longer walk. Even the commentary states the tunnel is “short”.

We could have idled about in there, but having touched the clammy walls and got our boots wet from the stream which ran through, there’s not much else to do. After the immensity of the Wheel, the tunnel was a bit of an anti-climax.

As Adrian Mole once said about another landmark, we had “been there, saw it, came back”.

Inside the adit to the Great Laxey Mine. Photo Wikipedia. (Copyright)

Luckily, we can turn back the clock and see Laxey Mine nearly 150 years ago, via an eyewitness, an unnamed reporter, who went below ground to “see for himself” as he doubted the veracity of highhanded statements bandied about the island: that the Great Laxey miners were not worthy of a rise in wages; that they had an easy life underground.[3]

Our own selfie, taken in pitch dark, is eerie. Our photographer managed to get herself in the picture. Or is she a ghost?

I imagine this young man, (he sounds young me), educated, perhaps even with a posh English accent, and I suppose the miners, who probably spoke Manx among themselves were wary of strangers. Certainly, they were initially “diffident” towards him, but persistence paid off, and at last he “dropped on the right man” someone who was experienced at the lowest levels of the mine. An arrangement was made, and the reporter and his guide met by the Laxey Wheel on a May night in 1875, at ten o’clock, a time when workers would be above ground and there would be a clear course from shots and powder smoke.

The entrance to the mine, said our reporter, was constructed in such a way “as to keep strangers out”: for this to be the portal through which 300-400 miners passed at any one time, he said, was “ridiculous” also dangerous and uncomfortable to travel on.

“It is only a running stream about four foot wide, and one foot deep in the centre of which are the two tram rails on which the waggons run. These rails are just above the water and on them, straddle ways, the men must walk, eighty to 100 yards, to and from going to work.”

After only a few yards, he fell off the rails and after twice attempting to regain his balance, he gave up and walked the rest of the way, his gutta percha [4] boots no match for the running stream. Arriving at the end of the tunnel with wet feet, and with water from the rock above dripping gown his back, he saw the dimensions of the hole in the ground through which they were obliged to descend,

“….. no more than two feet square [it] reminded me of a coal scuttle on a very wet and sloppy day.”

He was wearing layers of warm clothing, but his guide told him to strip down to his shirt and trousers. They lit candles and stuck them on clay balls in front of their stiff felt hats.

“My guide leads the way and after repeated injunctions to ‘Hold fast with the hands’ he steps on to the ladder and I ‘follow the leader’, but no sooner his head emerges from the hole than the lights go out in both hats, and we are left in complete darkness. Knowing the sudden drafts at this junction, my guide brought with him a plentiful supply of ‘Co-op sulphurs’ which are proof against damp but no sooner our head torches are lit again, then out they go.”

Repeated attempts to keep the lights going failed and they continued to descend with the guide holding a candle against his chest with one hand, whilst holding on to the ladder with the other. Our young man found himself “considerable shaky”. He likened his experience to being in a balloon, whilst going down a ladder as straight as a wall and dangerous from the looseness of the binding spokes as well as slippery and slimy from clay, running wet and the accumulation of hundreds of feet pounding them daily. The guide, being used to it, was relaxed. At the bottom of the first set of ladders, the draught of air was not as strong and the candles stayed alight, though only illuminated four or five yards around them. This was probably a blessing, our reporter thought, “as if the climber had full vision his imagination would cause more accidents than actually take place in these deep mines.”

They now inched along a level cut into the rock to the next part of the descent via more of “these fearful ladders”. The first sets had been four to five feet in length; those they now descended were mostly 120 feet long. After each one they paused briefly on a landing five or six feet square, before getting on to another ladder of the same length going further down. At this level the rocks had formed fantastic shapes, like beehives or huge icicles of mud. The unnatural stillness gave way to a supernatural wailing. The guide called “Come on and have a sight of the pumps” and they came upon the engine shaft down which the pumping machine worked. Below this at the 200 level the pumping rods ran horizontal along the level. They descended to 220 fathoms, where only a few hours before the men had been working the richest ore in the Great Laxey Mine.

“It was a splendid sight, the sides and roof sparkling with pure lead and blende. My guide took a pickaxe and climbed up four or five fathoms and began to fall the loose hanging rock, bringing down pieces of pure solid metal as large as my head.”

Even after two hours ventilation the place still hung black with powder smoke.

“I found it difficult to breathe and the perspiration was running down my back from the heat. I bathed my hands in the stream of warm water which ran in a level close by.”

Though not quite at the deepest level, (the pumping shaft was ten fathoms lower) both needed the rest. They took the opportunity for a chat, along with “the miners’ consolation, a pipe.” The following (much abridged) conversation took place:

“Do you always go straight to your pitch work from the ladders?” the young man asked.

“No. We take a rest of about a quarter of an hour to cool the sweat before we can go to work.”

“Could there not be some means devised where the men could come down in cages as they do in coalmines?”

“These mines are different to coalmines where the shafts are driven down perpendicular. In this mine the shaft is driven on an inclined plane. The means [to instal mechanical means of descent and ascent] would be difficult but not, I believe impracticable. We often talk of these matters when we take a rest at the levels. I believe it could be done for far less money than was spent foolishly on the Ballycraggy Reservoir and a thousand times more advantage to the Company and to the men. It takes every man an average of two hours to come and go from his work after he enters the mine, so there we have two hours out of the eight, labour and sweat, spent in vain. And let me remind you that the work on the ladders is far harder and more tiresome to the body than work in the pitch; as you yourself will believe before you get to the top.”

The talk turned to the benefits the Company would derive investing in a different system. If men were fresh to their work, the guide said, they could do more in the same amount of time. He went on to provide detailed figures to back up his theory. At length, he stated there was not a man in the mine who would not prefer working than use his time climbing the ladders.

The fearful ladders are re-imagined on the Miners’ Memorial.

The reporter expressed his amazement that the improvements outlined had not been adopted, whereupon,

“Tut,” said the other. “How could you expect such undertakings to be entered into when the whole energy of the Company has been employed in making valuable each other’s property?”

When he continued to express his views, the reporter saw they were getting into murky political waters…… “finding my guide waxing rather warm, like the atmosphere we were then in, I thought it best we should get into cooler air.”

So having fixed more soft clay into their helmets, they lit new candles, and the ascent began, the reporter walking carefully in his guide’s footsteps especially at 190 fathoms where the level was uncovered at the sides sufficient for a man’s body to slip through into holes twenty yards deep. After this they “buckled on” in earnest. If it had been hard work coming down, then it was even more strenuous coming up: “the whole weight of the body has to be lifted stave by stave by the arms and legs, and besides this, a sickening smell rose from the bottom of the mine.” He compared the stench to rusty iron being boiled up in water with brimstone added.

“In the fumes you have something of what the miner inhales underground. No wonder, thought I, at the lead miners being a race of sickly, sallow-complexioned men when the nutrient of their bones is drowned out of them by sweat and their stomachs and lungs constantly taking in an atmosphere of loathsomeness and powder fumes. No wonder their stomachs are ‘ticklish’ and their appetites bad, that they cannot do with coarse food as those who work outside. It would waste the best constitution that ever existed.

“After going through this mine and seeing the places where the men toil and sweat for a bare livelihood in dirt and darkness [……….] I should like those who are fond of talk at the Great Laxey Mine half-yearly meetings who say that 26 shillings a week is too much, to be forced once a day for a week to descend on ladders to the 220 level and back again. I would not want him to strike a blow with a hammer or touch a jumper, but I believe that before the week was out his view would be considerably changed. People have very little idea when they hear that Great Laxey Mine is now sunk to 230 fathoms, a very great depth that is, into the bowels of the earth, the whole of which depth has to be climbed upon ladders nearly straight.

“But here we are at the top. Thoroughly tired as far as self is concerned, and back through the long level, we came through in darkness last night. Daylight is breaking and like Hamlet’s ghost, methinks I scent the morning air.”

—————————————————-

After this bit of time travel it’s back to the present and to us. Smart phones are all very well, but I would have liked a definitive ‘Book of the Wheel’ and the twin mines. There are bound to be books in the café, the daughters felt. There were, to be sure, but they were all about the premier local oddity, Manx Cats. We didn’t see any of these furry creatures in the flesh, but Celia bought one portrayed on a key ring.

The next day it was back by tram to Laxey, all change, and a turn up the side of the hill aboard the Snaefell Mountain Railway train. The two mines, Great Laxey and Snaefell were perched on the hillside, one above the other, Great Laxey nearest the village, and Snaefell Mine halfway between it and the summit of Snaefell, “Snow Mountain” in old Norse. The Vikings, who conquered the island, must, like George, have had their origins in the flat land of Denmark, rather than Norway, and were perhaps awe-struck by the enormity of its 2037 feet towering above sea level. I felt a pang of regret for times past when two or three ramblers with rucksacks got off at the halfway stage, as any mine enthusiast more active than I should do. They would have found mining relics as depicted on the website [5] but all we could see from the train was, in the far distance, this ruined hut:

The next day it was back by tram to Laxey, all change, and a turn up the side of the hill aboard the Snaefell Mountain Railway train. The two mines, Great Laxey and Snaefell were perched on the hillside, one above the other, Great Laxey nearest the village, and Snaefell Mine halfway between it and the summit of Snaefell, “Snow Mountain” in old Norse. The Vikings, who conquered the island, must, like George, have had their origins in the flat land of Denmark, rather than Norway, and were perhaps awe-struck by the enormity of its 2037 feet towering above sea level. I felt a pang of regret for times past when two or three ramblers with rucksacks got off at the halfway stage, as any mine enthusiast more active than I should do. They would have found mining relics as depicted on the website [5] but all we could see from the train was, in the far distance, this ruined hut:

In the bright sunshine on top of Snaefell, it seemed as though a miner’s tramp to work might even have been pleasant, but such facetious nonsense was dispelled a day or so later, when travelling across unfamiliar country, through hills we had thought benign, our small hire car with the four of us inside was suddenly engulfed by a dense sea fret. We could see nothing in any direction from our tomb. The weather had turned treacherous in a flash. If this was what it was like in June, what was it like for the miners in December, with fog, rain, hail and blizzard as companions on their daily trudge?

At its peak, the Great Laxey complex produced a fifth of all the zinc extracted in the UK. The greatest loss of life in a single accident at Snaefell Mine took place in May 1897 when fire broke out at the 130-fathom level. In 2015, a Memorial was raised to these men, and to others who died in the drip of singular accidents in both mines.

You pass the paved memorial square on the way to the Laxey Wheel. The centrepiece is a 13-foot obelisk on top of which is a crouching miner carved in Carlow Blue limestone. The figure, weighing a tonne, wielding a pick and wearing a candle in his hat, was sculpted in Indonesia by Ongky Wijana, and funded through the generosity of a Laxey resident, Mrs Phillis Tate, born in 1915, who sadly died in 2012, so did not live to see the completion.

At the unveiling the sculptor said. “These guys were tough but often looked weather-beaten, sunken-cheeked and worn out. They had a solidity to them and a determination in their eyes that I wanted to capture. They were tough, hardy men who worked in very difficult conditions.”[6]

The twenty fatalities of the Snaefell disaster of 1897 died from carbon monoxide poisoning, but individuals were killed in other accidents, 1813-1912, “Fell down shaft.” “A fall of rock.” “Crushed by a wagon.” “Premature explosion of dynamite.” All sickeningly familiar to me, but the most frequent cause of death before the Wheel was constructed was “Drowned”. Even so, in 1904, another four men drowned, long after the Wheel was in full operation. Significantly, none of the deaths were due to the “breaking of the rope”. All because of the diabolical ladders. I have to say that the ladders stick in my mind to the extent that I often think myself hanging by my arms, and hauling my body up, one deep rung at a time, when trying to sleep. The imaginary exhaustion engendered beats counting sheep any day of the week!

One small snippet of information caught my eye during my trawl through the newspapers. We all know of the “canary in a cage” which was usually sent down a mine as a detector of gas. Perhaps canaries were in short supply on the Isle of Man. Mice were plentiful. They were lowered and sacrificed with the same sad, though useful, result.

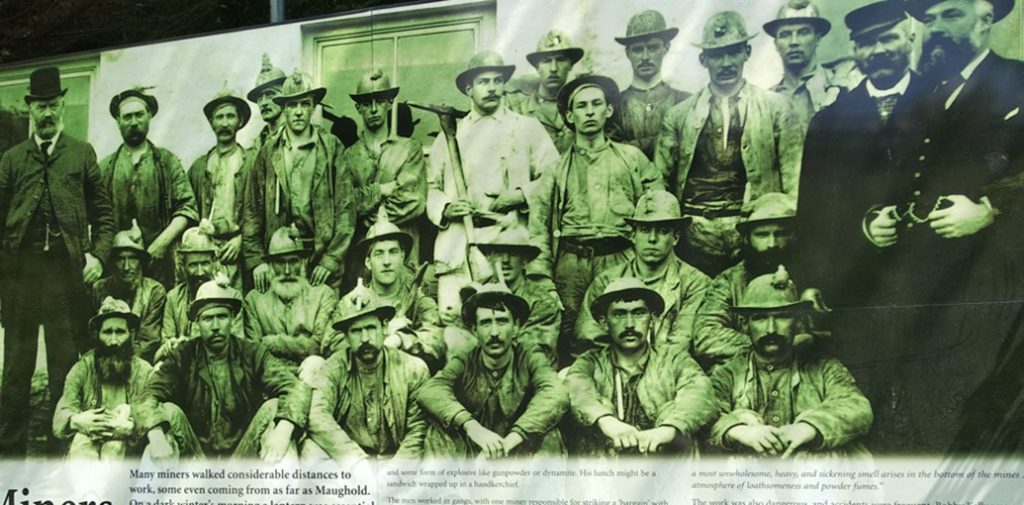

My photo of the billboard with the miners of Laxey, taken 20 June 2023.

[1] The Foxdale Heritage Centre. Information on https://www.facebook.com/foxdaleheritage

[2] YouTube: https://www.google.com/search?q=laxey+wheel+youtube+video

[3] The Isle of Man Times, 15 May 1875

[4] I had only previously come across gutta percha in golf balls. It was a kind of proto plastic. You live and learn.

[5] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Snaefell_Mine

[6] https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-europe-isle-of-man-32740339

A version of this article also appeared in the SGMRG newsletter no. 66, Summer 2024.

Blog Comments

Kevin Lindegaard

18th August 2025 at 9:19 pm

Whoops – I was supposed to post this two years ago but somehow I must have missed it in my inbox. I was doubly found out when Mum realised I couldn’t possibly have read it based on the gap in my mining knowledge during our Irish visit to Allihies Colliery in Cork back in April. Slapped wrist for Brutus!