The Brislington Richard Turner would have recognised. Today, the old pub, The White Hart, closed for years, is in a very sad state.

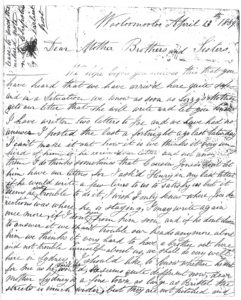

The two letters partially reproduced for this article were sent in 1859 by a Brislington man, Richard Turner, to his widowed mother, Mary, and the family back home. He and his wife Liz had emigrated to Australia the year before. The letters mostly tell of homely matters, their day-to-day life, the saddest being the miscarriages and still births suffered by Liz over a very short time.

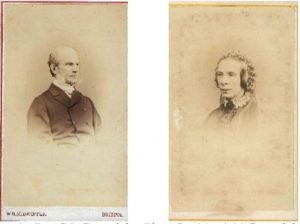

Prior to emigrating, Richard had been a live-in manservant in the household of Brislington’s curate, the Rev George L. Cartwright and his wife Anna Maria.

The Rev. George Cartwright & Mrs Anna Maria Cartwright of Brislington. (Copyright Gary Hynard)

(NB.Cartwright was one of three brothers-in-law who in succession became Curate at St Luke’s, Brislington. )

The Rev. George Cartwright & Mrs Anna Maria Cartwright of Brislington. (Copyright Gary Hynard)

The quality of Richard Turner’s writing is remarkable and gives a laudable tick to the village school he is likely to have attended. The principals of two local schools during the years Richard was of an age were Sarah Allpass and Mr Taylor. There are grammatical slips in the letters, but these may reflect his manner of speaking. To avoid the frequent use of “sic” or presuming to make corrections, I have left them the way they were written more than a hundred and fifty years ago.

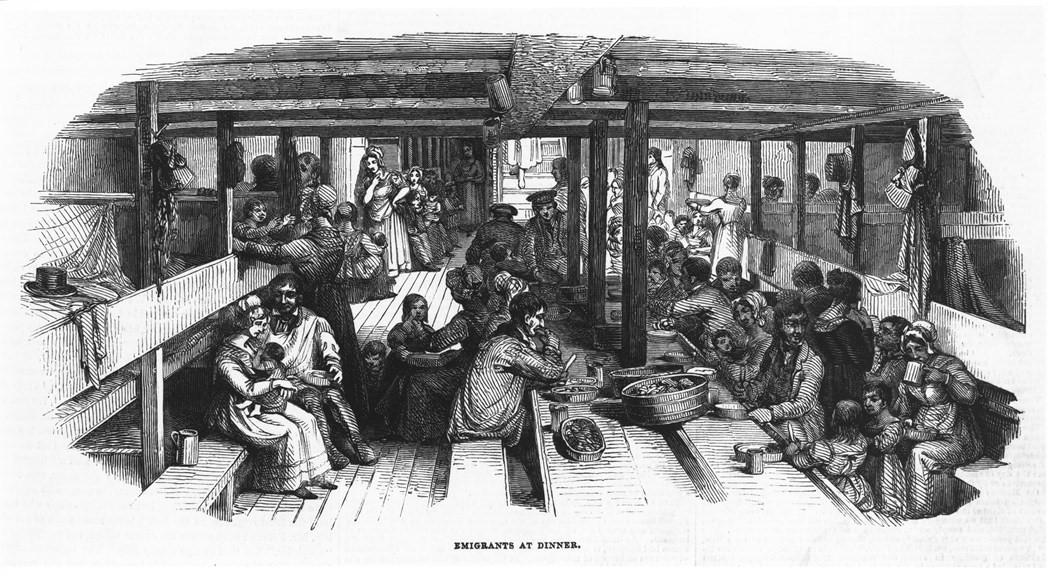

Richard was twenty-five when he and Liz (nee Elizabeth Wheel) aged 22, were married at St Matthias Parish Church in Bristol on 27 September 1858. The idea of leaving behind family, friends, and everything with which you are familiar for a faraway new life is a daunting idea which even today is not something entered into willy-nilly, without months of swallowing hard and a very dry mouth. How much worse it would have been in Richard and Liz’s day, without the speed of travel and instant communications we take for granted! And, for them, the likely prospect of never going home again? I admire their pluck, as I admire the pluck of the hundreds of thousands of others who like them set out with similar trepidation and hope, and those facing journeys even more hazardous today.

Just two months after their wedding day, with tears all wrung out and the last farewells chokingly uttered, Richard and Liz, were at Plymouth Harbour, where they went aboard the ship “Hornet”, 1,165 tons, under Captain Thomas Grieves, part of an intake under a Government Emigration Scheme, bound for Sydney. It is likely the journey in the “Hornet” was powered by a combination of steam and sail. In the 1850s, steam technology alone would have been too risky to be relied on for the whole voyage.

The Turners joined 436 other hopefuls crammed into every available space, whose welfare would be entrusted to Surgeon-Superintendent Andrew Sexton Gray MD.

Life at sea was uncomfortable at best. Hopefully Richard and Liz were not accommodated in “steerage” the lowest deck of all, below the water line. Hygiene in the crowded conditions was poor, (the stink alone must have been sickening), ideal conditions for the spread of disease. In bad weather “Batten down the hatches” meant exactly that. The Turners would have heard this unwelcome order far too many times in the rough journey we know they endured. In bad weather passengers on the lower deck were confined below with no ventilation, perhaps even without light, the use of candles and oil lanterns usually forbidden due to the risk of fire. There were straw mattresses, hemp, ropes, timber, tar and all manner of lumber necessary for the voyage lying about. Fire at sea was only one of the many hazards which could lead to disaster and certain death. Too many vessels were lost without trace. Even with enough lifeboats to accommodate the numbers, (rare) rescue was unlikely. Those who could swim had no hope of reaching the shore. Professional seamen, notoriously superstitious, could rarely swim, not only because they believed it tempted fate, but it prolonged the agony of drowning.

The “Hornet” sailed safely into Sydney Harbour on 3 March 1859, after a gruelling 113 days at sea.

“…a rather long passage having been particularly unfortunate with foul winds and bad weather throughout. After clearing the Channel she had an succession of heavy gales lasting 22 days. Since rounding the Cape of Good Hope she has had light winds….”

…. which doesn’t sound too bad, except, they…

…… “blew N.E. to S.E. There were five deaths and six births on the passage.”

The Australia & New Zealand Gazette, 17 March 1859, states the head count stood at 438, the same number with which they had started. If all the babies survived, then there was a tiny “plus one”.

The first letter dated 13 April 1859, addressed to “Dear Mother, Brothers and Sisters”, confirms the newspaper report:

The first letter dated 13 April 1859, addressed to “Dear Mother, Brothers and Sisters”, confirms the newspaper report:

“We had nothing but head winds and rough gales which lasted about 24 days”, Richard writes. “I have made a diary of our Voyage in a Book. We are going to send it to Liz’s mother, and when you see any of them, they will let you see it.”

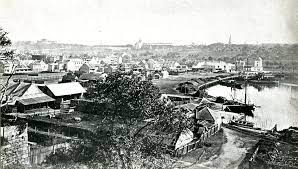

“We shall do very well here. Sydney is a fine town as large as Bristol. The streets is much wider, but they are not pitched and paved the same as they are home. There is shops of all descriptions and large hotels. The beer here is 6d a pint. There is none sold cheaper. It is brought over from England. Wines and spirits is near about the same as at home. Mother, I can’t get my pint of Burtons for 2d a pint at all now. I have 2 or 3 glasses of beer a week, so it is just as cheap as at home. For all the beer is so dear, there is plenty of drunkenness going on here.”

As to other provisions, tea, an expensive commodity, was 2s 6d a pound, beef from 2d to 3d a pound and mutton 3d to 4d a pound. Pork and bacon were more expensive.

Richard pronounced everything very good, including an abundance of shops, churches, chapels and schools. Sydney Gardens, where he and Liz walked on Sundays, was free to all.

Sydney Gardens (This beautiful historic photograph is the copyright of the National Trust, Australia. With thanks)

Sydney Gardens (This beautiful historic photograph is the copyright of the National Trust, Australia. With thanks)

“The water is beautiful and soft,” he tells his mother. “If you was here taking in washing you could do well for washing here is rather dear. You could dry all your clothes out of doors winter and summer, but I don’t think you would stand the heat in summer for it is very hot.”

They had taken less than a week to find work. On the 8th March they had had been engaged for six months, at £40 per annum, all found, by a “Professor of Dancing”, Mr W. Clark of 75 William Street, Wooloomooloo, a suburb of Sydney. Richard’s job was to clean two large dancing rooms, “one here, the other at Pitt Street”, whilst Liz did the washing and housework.

“When I have got nothing else to do, I helps my old woman. This is a very gay place. We have dancing here 4 nights a week, young men and girls. They keeps it up till 11 o’clock at night.”

After this cheerful news, the next item comes as a great shock, which leaves no doubt that such tragedies were treated with stoicism, a fact of life.

“Dear Mother, about a fortnight ago, Liz had a miscarriage of a two month and fortnight old child. She was took in the morning and it was over by 3 pm. Our people was very kind to her. The Missis seen to her and gave her a glass of hot brandy and water. The old gal kept up very well thank God.”

In a complete change of tone he goes on:

“The Musquitoes bites newcomers very much and it hitches dreadful. They come out at night and bites us when we are asleep. You would all laugh if you was to see how we dress of a night going to bed to keep them from biting us too much. I puts on my drawers and stockings and the old gal puts on her drawers and bedgown, nightcap and stockings and gloves. We laughs at one another a good one before we put them on. My poor old bum and legs was bit awfull and as was my old woman’s but they are tired of us now.”

Much of the rest of the letter is taken up with Richard’s obvious bewilderment that his brother Joseph who had gone out to Australia before them had not been in touch. He had written to Joe twice and received no answer. He clutches at straws and makes the excuse that perhaps

“Cousin Jones don’t let him have our letters”. If not, he continues sadly,

“we thinks it very unkind of him if he receives our letters and not answered them. I may write again once more if I don’t hear from him soon and if he don’t choose to answer it, we shan’t trouble our heads any more about him. We thinks it very hard to have a brother out here and not trouble himself about us. I should like to know whether he sent for me as he said he would, he seems quite different now, dear Mother.”

Remembrances are sent to “Bill”, who is not yet married to “our dear Mag Jones”, who is asked to write them, also to “Uncle and Aunt Leg” of Limekiln Lane, Bristol, as well as “kindest loves to you dear mother, Sarah, Tom, Sophia and the dear children Mary Ann and William and we hopes all are well.”

Just before the end he suddenly slips in a surprising one-liner “tell Brother Tom trade is very dead here at the moment.” He gives instructions to sister Sarah to read the letter aloud to the family which suggests she was the best reader among them, and to write back soon,

“from your Ever affectionate and dutiful son and daughter,

R & E. Turner.”

The next letter dated 13 November, 1859, gives a new address, “Woodstock Cottage, Wooloomooloo.”

“We hope you are all quite well and dear Mother we are anxious to know how you are getting on for I often thinks of you and that you are almost knocked up”.

Richard was still fretting over the prodigal Joe.

“We thinks it very hard brother Joe don’t write to you and help you for I am quite sure, Mother, he being single, could do it very well if he likes, for any single man, if he is steady and industrious, can do well out here. There is many that have not been out here so long as he has, have done well and set up in a little business. We have not had a single letter from him but the one James Jones wrote as I told you of. I may write another letter to him soon, if he don’t answer it we shall give up all thoughts of him.”

“Now I tell you a little about us”, he continues. Liz had immediately become pregnant after her miscarriage, but again, there is tragic news.

“In the last letter I wrote I told you that Liz was in the family way but I am sorry to tell you that she was confined three months before her time. She had twins, both girls, and what was more strange, they was born with teeth and with nails on their toes. Liz is getting on very well, thank God. She is downstairs today. She was confined on the 3rd instant. It was brought on by a fright. Our coachman went and got drunk a week before she was confined and he came home, and abused and cursed and made such a noise that it frightened her and that brought it on. He was turned out of place directly and Master sold the horses. Now he only keeps one horse to ride and drive out in the dog cart. I have that to look after, dear Mother, and the Old Lady, where you directs our letters to now. I can assure you all if Liz was a lady she couldn’t be more attended to than she was. The people we are living with are very good to her and they won’t let her do anything until she gets strong again.

“The country round here is beautiful and our summer is just coming in. It is getting very hot and we don’t see a drop of rain for several weeks. We send you a little view of some parts of Sydney by next mail. We hope Thomas and his family is well and also got plenty of work. And Sarah, Mary Ann and William we hope are quite well. There will be a little enclosed with this, give it to him for his beloved Margaret. We hope her and all belonging to her is quite well. Now I must conclude with our kind loves to you all, Mother, brothers and sisters and also give our kind loves to John and Mary Headford and the boys, young men, rather I suppose. Tell George to write. I wish he was out here. I give all our loves to all relations, enquirers and friends, Bill must write down the country and tell them the news so no more at present

from your ever affectionate

R & E Turner.

Write often. Tell Bill to go down to Limekiln Lane and give our loves to Uncle and Aunt Leg and tell them the news and that we are doing well.”

Direct to Mr Logue

No 3 Riley Street

Wooloomooloo

Sydney, New South Wales.

Wooloomooloo Bay, Sydney, NSW, Australia, 1850s. (copyright Sydney Archives, with thanks.)

Richard Turner was born on the 20 February 1833 and baptised at St Luke’s, Brislington, on March 17th, the son of Richard, a carpenter and Mary Turner, nee Ford.

His siblings were Sarah, born 1825, Thomas,1826, Joseph, 1827, Mary Ann, 1830 and William in 1840, presumably “Bill” in the letters.

Richard and Liz had five more children, but it appears that only Charles Wheel Turner, 16 December 1860, and George A. Turner, born in 1862 survived, both living into the 1930s. At the time of his son Charles Wheel Turner’s baptism, Richard was a gardener at Paddington, New South Wales, another suburb of Sydney.

Richard died in 1867 aged only 34 and Liz in 1879.

In 1841 Richard’s mother Mary Turner was living with her children at Kings Arms Lane, Brislington and in 1851, (when Richard, 18, was resident with the Cartwrights at Rose Cottage) she was aged 43, with two adult children at home, Thomas aged 25 and Mary Ann aged 20.

Mary Turner had left Brislington by 1881, and aged 78, was living at 9 Mary Street, St Philip and St Jacob, Bristol, touchingly described as “supported by her children”. Nearby, in number 12 Mary Street, lived her son Tom, aged 55, a carpenter, his wife Sophia, 57, and their sons Francis, 22 and Alfred 16. William Wheel. Liz’s father, a retired coachman, aged 81 was living at 6 Eugene Street, St James, with his son George, a stableman, aged 33.

It is not known what became of the diary which Richard kept of their adventurous voyage which was sent to his mother-in-law, Liz’s mother, Sarah Wheel. It may still be with the Wheel family. Wouldn’t it be marvellous if this article reveals its whereabouts?

I am grateful to present day Turner descendants Eunice Jones and Sheila Packer who entrusted me with their treasured family letters. To my surprise I see that Sheila first wrote to me in 1994 and Eunice in 2000. All that time, all those words, all my life. Thanks also to Gary Hynard, a historian with special interest in the Cartwright family for permission to use his photographs of George & Mary Ann Cartwright.

The illustration which heads this piece, “Married Emigrants in Steerage, 1844” is from a historical edition of The Illustrated London News, and is reproduced courtesy of

https://museumsvictoria.com.au/immigrationmuseum/resources/journeys-to-australia/

This site also contains useful general information on emigration to Australia.. With thanks.

I am making a long overdue attempt at housekeeping my computer files and resurrecting some items that have been lurking within. This article is a reworked version of a piece in the Parish Magazine, “Brislington Village News”, March 2000.

Leave a Comment