Peace with the infant republic of America was declared in August 1783. With the small detail that Britain had lost the war apparently discounted, it appears that the arrogant assumption was made that everything had returned to normal, that transportation would carry on where it had left off seven or eight years previously. Almost before the ink was dry, a merchant ship the ‘Swift’ had been hired and made ready for the voyage. She was due to sail for America from Blackwall on the Thames on the 17th August with eighteen crew members plus a cargo of one hundred and forty three convicted men and women.

The prisoners, confined between decks and in irons, were allowed on deck, eighteen at a time, to exercise, though still fettered. On the 28th August they sent a message to the Captain asking him to remove their irons. He refused.

They replied, ‘Well in that case we will take them off ourselves.’

He answered with a warning: ‘Think carefully. Be advised that in that case I shall fire on you.’

The prisoners said ‘Fire and be damned!’

The following day, ‘they took off their irons with as much ease as if they had none on.’

Soon with all these desperate people wandering about the ship without much control, the inevitable happened. The crew, the captain among them, vastly outnumbered, were quickly rounded up and imprisoned.

Some of the convicts were for escape, whilst others were bemused and terrified. The most moderate among them gave terrible warnings of the consequences. ‘Mutiny’ and ‘returning from transportation’ were both crimes for which capital punishment was likely to be carried out but their arguments failed to convince the rest. Between Dungeness and Rye, the ship dropped anchor and at about six in the evening ‘forty eight of the most reckless’ seized the boats and taking arms and ammunition rowed to the shore.

The remainder, left on board had little idea how to sail the ship, so proceeded to get drunk.

Thomas Bradbury, mate of the ‘Swift’ gave his version of events.

‘About twelve o’clock at night we informed them of the dangerous situation they were in, in case the wind should come up and they would lose their lives. So they agreed to let the sailors up and we bore away. At about half past three, as they had been drinking pretty freely, they began to grow drowsy and went below.

‘There was not above half a dozen left on deck, and so we got possession of the ship, and brought her to Portsmouth.’

So the mutiny fizzled out. But a hue and cry was raised. The majority of those who had gone ashore were recaptured and brought to trial at the Old Bailey.

The case against Charles Thomas rested on the fact that he resisted arrest and hit one of the officers with a poker. His original sentence had been for stealing a tub, value one penny and five shillings worth of butter.

William Matthews, who was with Charles Thomas, also resisted arrest, brandishing an offensive weapon, a knife. His sentence had been for the theft of a wicker basket and 111 dead pigeons.

Thomas Millington’s crime had been more ambitious: the theft of cloth valued more than £100. No specific evidence was given against him for the mutiny and it was even said it was not known whether he had been amongst those who had taken the arms. Nevertheless he was pronounced guilty. Asked whether he wished to say anything before sentence was passed his reply was tragic: ‘I have nothing to say, my heart is quite broke.’

Christopher Trusty, a convicted armed robber, was alleged to have been the first to go to the Captain’s cabin, where he stole the buckles out of the Captain’s shoes. He was said to have knocked down two or three of the dissenting prisoners as he charged towards the boats to make his escape.

David Hart had been convicted for stealing cloth. He stated that he had taken part in the mutiny under duress; that a pistol was forced into his hand shortly after he had been drinking rum with the Captain. When apprehended ashore he said he had been on the way to give himself up. The Jury did not believe him, although another prisoner, Charles Keeling, spoke as to his innocence.

Abraham Hyam, previously tried for the theft of clothing was stated to have taken an active part in getting the weapons and taking the boats.

These six men were hanged at Tyburn on the 26 September 1783.

The remaining mutineers were recommended to mercy and pardoned on condition of resuming their original sentences of transportation. Among them were Andrew Dickson, Joseph Pentecross and George Nash; they had gone quietly when apprehended by a kindly innkeeper, Richard Taylor, who spoke up for them in court ‘They behaved as well as could be expected in their unhappy situation. I am very sorry for them.’

One of those convicted of the mutiny was a sailor, Joseph Dunnage, who ironically might have been of some use had he stayed aboard the ‘Swift’. His original conviction had been for the bizarre theft of a carriage-door window. His death sentence was commuted to transportation for life.

Meanwhile, the ’Swift’, possibly under the same crew, including Tom Bradbury, and with those convicts who had not tried to escape, continued her voyage to Maryland, and oblivion. Maybe the ship foundered or her cargo of souls were accepted after all by the Americans and put to work.

Some of the ‘pardoned mutineers’ were transferred from the prison at Newgate to a Hulk, one of a number of old vessels, no longer seaworthy, which had been dismasted and moored near various coastal towns as ‘temporary’ prisons for those awaiting transportation.

‘On their arrival on board they began with great facility to pick the locks and take off their collars, declaring for freedom and declaring vengeance on all who should oppose them. A scuffle ensued in which three of the most notorious were shot by a party of the militia, who with the sheriff attended them to the ship.’

William Blatherhorn[e] had been tried at the Old Bailey for the theft of eleven yards of printed cloth and twenty four cotton handkerchiefs, total value £2. 10 shillings and sentenced to seven years. He had not only been ‘pardoned’ for the ‘Swift’ mutiny, but during a previous riot at Newgate he had reportedly stabbed an official. Though shot in the neck during that disturbance, he survived. A second man caught up in the melee, John Perry, took ‘a ball in the breast and died on the spot.’ A third, Andrew Dickson, who was one of the woebegone trio captured by Richard Taylor the innkeeper, also died when he

‘leaped into the Thames and received a ball in the back of his head from which he immediately sank.’

The Sheriff and militia were congratulated for preventing the escape of such ‘a horrid set of miscreants’, two of whom, Blatherhorn and Dickson, were allegedly the ringleaders of the riot. Blatherhorn maybe, but Dickson, surely not, even from the little known of him. He may have been a frustrated musician. His conviction was for the theft of two French horns, and some brass trumpet mouth pieces.

Undaunted by the unrest, the government chartered another vessel, the ‘Mercury’, which in March 1784, set sail for America. Like its predecessor, ‘Mercury’ had been leased from a merchant, another beacon of glorious free enterprise. Among the women on board were two who would later have a connection with Bristol. They were Mary Kimes and Ann Randall.

Mary Kimes, a Londoner, was born at Holborn in 1756 as Mary Potten. She was tried as Potten in December 1783 and convicted at the Old Bailey for the theft of 13 yards of silk. She was sentenced to 7 years transportation to His Majesty’s dominions in America. Three months later in March 1784, she was put in irons, loaded into the gaol wagon and taken to Blackwall and the ‘Mercury’.

Ann Randall, alias Cox, had been accused of stealing two pieces of printed cotton, otherwise known as ‘bundling the muslin’, on Christmas Eve, 1782 from a widowed shopkeeper, Ruth Roberts.

Ann and two other women, Mary Dymacks and Sarah Pond came up for trial at the Old Bailey three weeks after the crime on the fifteenth of January 1783. Mrs. Roberts told the court that they came into her shop at Poplar and ‘the small one’ asked about black stockings, which she showed them, after which they moved about, making small talk about the weather – it was a very cold day – and one, ‘the tall one’ moved close to the counter where the cotton lay. Mrs. Roberts told them the stockings were priced at 1s 10d a pair – (quite dear. about 9p in today’s money, and certainly more than a day’s wages at the time.) The women began to barter. Mrs. Roberts said

‘The tall one whispered to the middle one and she bid me 3 and fourpence for the two pair. I said I would not take it, and they all turned round, saying they would not offer more, and went away. As soon as they were gone I saw the bits of cloth were missing. I sent a little boy after them to desire them to come back, for I was certain they had robbed me, but I did not dare leave my shop.’

When the boy had no luck in persuading them to return, she sent another employee, young Hannah Thacker, after them.

Hannah was sworn.

She said ‘My mistress sent me in pursuit of the prisoners at the bar. I pursued them. They were never out of my sight. They saw me coming after them. They went up to a barn in Cole Lane, and I saw them put the cotton into a hole in the barn. I asked them to come with me, and they said they would.’

It is astonishing that they concurred so readily, but it seems that very few people resisted arrest, even if challenged by a young girl.

Hannah went on: ‘I took them to my mistress’s shop, and the little one said “We will make them smart for it.” My mistress sent for a constable and when the prisoners went to the watch house, I went to the barn and fetched the cottons out.’ (The cottons were produced in court.)

Thomas Carpenter the constable was then sworn. His evidence was brief. ‘I am the constable. I had these cottons from the servant maid. They are the same.’

The Court to Hannah Thacker: ‘Is that the same you took from the barn?’ Answer: ‘Yes.’

The Court to the Prosecutor: ‘Are you sure these things were there when they came into your shop?’ Answer: ‘I am positive of it.’

This was the case for the Prosecution.

As no lawyer was provided, each of the women was required to defend herself. In turn when questioned they all parroted the same answer.

‘“I know nothing of the robbery.’

This was the entire case for the defence.

The Jury found the women guilty.

The Judge said to Mrs. Roberts. ‘What is the value of these things?’ She answered ‘Thirty nine shillings, My Lord.’

The value was important. Mrs. Roberts was trying to help. Anything above £2 was less likely to result in a reprieve. Clearly Ruth Roberts did not want to have three deaths on her conscience.

So the women received the customary sentence, but were ‘pardoned’, in Ann Randall’s case, commuted to 14 years transportation. The other two disappear from the records. Quite possibly they died in prison. More than a quarter of all prisoners died of malnutrition, typhus – known as Gaol Fever – and other diseases.

Ann remained in London’s Newgate Gaol for two years and three months before she too was taken to the ‘Mercury’ where she fell in with Mary Kimes.

In true bureaucratic fashion, as soon they came on board the prisoners’ irons were knocked off, (government property) and replaced with those belonging to the master of the ship.

On 31 March 1784, ‘Mercury’ sailed for America, anchoring briefly in Portsmouth to pick up some West Country people, among them Francis Garland, the son of Samuel and Amy, from Mangotsfield, Gloucestershire, one of four men guilty of highway robbery, (muslin worth 133 shillings) at Winchester.

Also waiting at Portsmouth was a saddler, William Ayres, aged 21, another highway robber, tried at the same sessions. Francis Garland, Mary Kimes, Ann Randall and William Ayres became four of the contingent of 157 male convicts and 22 female convicts on board the ‘Mercury’. Love may blossom anywhere, and Ayres and Mary Kimes began a shipboard romance.

It might have been expected that a very close watch indeed would have been kept on the former ‘Swift’ mutineers, especially a desperado like William Blatherhorn who it will be recalled had already been involved in previous violent incidents.

He had so far escaped the hangman, and must have been considered one of the luckiest men alive, for he had carried a gun on the ‘Swift’ and his behaviour seems at least to have matched that of some of those who had suffered the ultimate penalty. If this was a novel I would cast him as a government spy.

At eight on the morning of Thursday the 8th April, when the ‘Mercury’ was about 75 miles west of the Scillies, the convicts rose up against the Captain and crew and took the ship by force of arms. They remained at sea for six days, apparently without sustaining any loss of life though one man had died before the mutiny. They might have succeeded in landing but were forced to turn back by the heavy weather. They eventually ran the ship aground at Torbay and scarpered.

On 3 May 1784 ‘30 upwards of them’ were said to be still at large, with six at least managing to get as far as Bristol and Bath.

Of the (apparently) few professional sailors among the ‘Mercury’ fugitives was one of a quartet arrested at Bath. Despite being locked up in the gaol they managed to escape once again and were front page news in the Bath Chronicle, 20 May 1784. In the absence of mug-shots they are described in fascinating detail, including their colourful attire.

Michael Andrews, ‘a seafaring man’, armed with a pistol when taken was about 32 years of age, 5 foot eight inches tall, well made, with dark curly hair. He ‘had on a sand coloured great coat, purple under coat, black velvet double-breasted waistcoat, white jean breeches, and black silk stockings.’

James Grimes, who admitted being one of the ‘Mercury’ mutineers, was 25 or 26, 5 foot nine or ten, swarthy, his complexion much pitted with smallpox, with black curled hair, and wearing an olive-coloured great coat, green shag waistcoat, brown corduroy breeches, flapped hat, dark silk and worsted stockings. His legs were ‘much swelled by wearing fetters and [he] has the venereal disease upon him so bad that it renders him quite lame.’

William Hill was about 25, well set, 5 foot six inches high, sandy hair, ‘much marked with summer moulds’[1], a down look, had on a blue double-breasted coat, with yellow buttons, fustian-coloured jean waistcoat, thread stockings, large silver buckles with brass studs in them, his legs much swelled from wearing fetters.’

Thomas Wiltshire was also about 25, stout made, 5 foot five inches high, fair complexion, brown hair tied behind. Less flamboyantly arrayed than the others, he wore a brown great coat, brown coat and breeches, black stuff waistcoat, black stockings and a flapped hat.

All four were discovered in a Bath lodging house. When resisting arrest Andrews fired his pistol and wounded two persons. After the escape they were believed to be making their way towards Warminster. The Bath Chamberlain offered a reward of ten guineas for each one secured.

They turn up again over a year later on 7 July 1785, once more in the Bath Chronicle, but minus Thomas Wiltshire:

They turn up again over a year later on 7 July 1785, once more in the Bath Chronicle, but minus Thomas Wiltshire:

‘William Hill, alias Michael Nowland, Michael Andrews, alias M’Nally, and James Grimes alias Macauley were removed from Shepton Mallet Gaol by habeas corpus to Newgate charged with being felon transports who escaped from the Mercury in April 1784.’

Thereafter there is no trace of them.

No official reason was given for either of the two mutinies which occurred so close to each other but both times the prisoners had believed, with good cause that America was not their planned destination. Charles Keeling, one of them, said

‘Some of the men informed us that if they could not dispose of us in America, they were to dispose of us in Africa. That was the reason for our first refusal.’

The convicts were right to be suspicious. It was well known that the government, desperate for somewhere to offload the increasing backlog of convicts, had tried to establish alternative penal colonies in Africa.[2]

Thomas Limpus, 1762-c1801, convicted, seven years transportation, in 1783 for the pitiful theft of a handkerchief, valued at one shilling, had first-hand experience. He had been imprisoned during one of these ill-fated experiments at Goree, off the coast of Senegal, a long time staging post for the slave trade. Limpus and nineteen other convicts had been landed on the island to act as auxiliary guards. He did not comment on the brutality but on the chaos and hunger.

He said ‘the soldiers were drawn up in a circle on parade. The Lieutenant of the island ordered us into the middle of it, and told us we were free men. He told us to do the best we could for ourselves as he had no victuals. There was a ship in the bay and I got on board this English vessel. I did not choose to get into the hands of the enemy. We lay four days in the bay before the governor would receive us. He said his troops were starving. When we came away, the island was given up to the French.’

The African experiment which has been sidelined in the general history of transportation proved disastrous. Three quarters of the Europeans died within months.

Limpus survived but once back in England was promptly arrested and sentenced to death, though reprieved for ‘transportation to America for life’. (Hope still sprang eternal in the breast of Empire.) He was discharged to the ‘Mercury’ and took part in the mutiny.

He was recaptured, sentenced to death for the second time, but again reprieved. By then ‘Mercury’ had sailed and he was put aboard the ‘Dunkirk’ hulk at Plymouth along with the majority of the West Country prisoners. He was imprisoned there for nearly three years before eventually leaving for Australia in 1787 aboard the ‘Charlotte’ as part of the First Fleet. He was among those relocated to remote Norfolk Island via ‘Sirius’ in 1790 when the colony at New South Wales was on the verge of starvation. He maintained himself there on a strip of land at Queenborough, having first cleared 40 roods of bush and scrub. In 1796 he was granted a conditional pardon, declared officially a settler and received appropriate rations. There is no record of his having married. He died, still only in his late thirties, sometime prior to 1801.[3]

Mary Kimes and Ann Randall escaped in the general mayhem. William Ayres and Francis Garland, a son of my 4 times great grandparents, along with William Blatherhorn, Charles Keeling and at least 90 others were put on trial at Exeter on 8 July 1784. These included a nine year old orphan, a ‘sometime chimney sweeper’, John Hudson. This child had been tried at the Old Bailey for housebreaking. In summing up the Judge addressed the Jury.

‘The boy’s confession may be admitted, in evidence, but we must take it with every allowance, and at the utmost it only proves he was in the house; he might have got in after daybreak, as the prosecutor was not informed of it till eight the next morning. The only thing that fixes this boy with the robbery is the pistol found in the sink; that might not have been put there by the boy: his confession with respect to how he came there, I do not think should be allowed, because it was made under fear; I think it would be too hard to find a boy of his tender age guilty of the burglary; one would wish to snatch such a boy, if one possibly could, from destruction, for he will only return to the same kind of life which he has led before, and will be an instrument in the hands of very bad people, who make use of boys of that sort to rob houses.’[4]

So what do you do? You send the child to live on a Hulk amongst some other very bad, or at least very hardened, people. That’s the solution.

Aboard ‘Dunkirk’ at Plymouth, where the rest of the convicted ‘Mercury’ men were also taken, John Hudson behaved ‘very well’. He would become a First Fleeter aboard the ‘Friendship’, and is believed to be the youngest known prisoner to be transported to Australia.

Artist’s impression by Philip Lock from the FirstFleet website.

Like Thomas Limpus, John was relocated to Norfolk Island in 1790. In 1791 he was sentenced to 50 lashes for being outside his hut after nine p.m. After 1795 nothing is known of him.

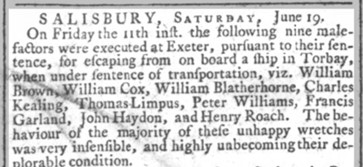

A sensational tale in the Hampshire Chronicle 21 June 1784 states that nine men had been executed at Exeter for the ‘Mercury’ mutiny. There was even some added horror:

‘The behaviour of these unhappy wretches was very insensible and highly unbecoming to their deplorable condition.’

Except that it wasn’t true at all. The reporter, carried away, had fallen into the trap of the ‘Death Recorded’ red herring. Everyone named was very much alive, and each one would become a First Fleeter. Except for Keeling (otherwise John Kellan) who was in ‘Scarborough’, they sailed to Australia via the ‘Charlotte’. William Brown had the misfortune to fall overboard and drowned in the South Atlantic, the rest arrived safely at Sydney Cove, which goes to show that you shouldn’t believe everything you read in the papers..

Whilst the hue and cry and the trials were going on ‘Mercury’ after necessary repairs at Torbay continued onwards towards America. On board were approximately 63 convicts who could not be arrested for mutiny as they had not managed to get ashore. Not made welcome in the new republic, the ship sailed on to Central America where she landed on the Mosquito Coast. Nothing more seems to have been recorded of ship, crew or convicts and so ended the system of transportation of ‘white slaves’ to America.

As to Mary Kimes and Ann Randall, over the next two months they very slowly left Devon behind. Beggars were routinely stoned and set upon by dogs. They must have kept going by stealing food and sleeping in ditches. They arrived in Bristol where they were discovered and arrested in June 1784. They were taken to Bristol’s own Newgate Gaol in Narrow Wine Street (not to be confused with the London fortress of the same name) where they were held on remand.

To be continued………

Read on – Chapter 2: The Inmates of Bristol’s Newgate Gaol – how the cons waited for years in gaol or hulks, whilst the govt got the new system going.

Title image: Merchant Vessels off the coast, 1783.’ by Thomas Luny

References

[1] I have no idea what this means

[2] Christopher, Emma. A Merciless Place – the lost story of Britain’s Colonial Disaster in Africa.

[3] Gillen, Mollie. The Founders of Australia.

[4] See www.oldbaileyonline.org/browse

Leave a Comment