In 1761, John Wesley who was interested in prison reform noted that Bristol’s Newgate Gaol was lately wearing ‘a new face’ and had changed for the better from ‘the filth, the stench, the misery and wickedness of previous days’. By 1784 when Mary Kimes and Ann Randall were detained it had reverted to type. The prison had a poor reputation. The premises housed not only convicts but also debtors, officially with space for thirty eight of the former and fifty eight of the latter. Now because of the backlog caused by those awaiting transportation, even though some were periodically removed to the hulks, overcrowding was a serious problem. Vice and disease were said to be rife. In the yard, male and female, young and old, were left to their own devices without employment or supervision. Youths would be taught new tricks by their elders and in turn they might instruct those younger still. Alliances must have been formed if only for self-protection.

Security was fairly lax, and to compensate for this, some of the worst prisoners were put underground into the Pit, which was seventeen feet round and with one small window. They were kept in shackles but no bedding or straw was provided, unless they could pay the jailer for such commodities. In 1786, a young man of twenty three, Ambrose Cook was in the condemned cell, prior to execution on St Michael’s Hill for highway robbery.[1]

The felons were kept alive – just, by an allowance of a pound loaf of bread before trial, and a pound and a half loaf on conviction, the bread and water diet which has passed into legend. The turnkeys were not paid regular wages and supplemented their incomes by selling privileges to the prisoners in exchange for extra food. It is not hard to imagine that some transactions were reciprocal. The otherwise ‘respectable’ debtors were charged 10½d per week for meals and had to hope that friends on the outside would oblige with the cash.

The inmates were cold and inadequately clothed as well as being half-starved. A begging bowl was set in the outside wall of the gaol in the hope that the charitably disposed would give generously to alleviate the suffering.

Small ads in the local press tell their own story:

25 September 1784, just a few months after Mary and Ann were admitted:

“… the Inmates in Newgate, 50 in number, give thanks to certain kind benefactors for a sack of potatoes.”

Christmas Day, 1784, festive cheer ‘…..the prisoners in Newgate give thanks for a quantity of wearing apparel, consisting of 6 jackets, 6 shirts, 12 pairs of stockings, 3 petticoats, 3 shifts, 12 rugs, by a lady and Rev Easterbrook. Also for a sack of potatoes and salt fish from an anonymous donor.’

(Rev Easterbrook was the gaol ‘Ordinary’ or chaplain. Among the less enjoyable of his activities was to accompany the condemned to execution. Salt fish, in earlier days a staple food of the Bristol poor is preserved for long storage by salt-curing and drying until all the moisture has been extracted. Before it can be eaten, it must be rehydrated and desalinated by soaking in cold water for one to three days, changing the water two to three times a day.[2] )

On New Year’s Day, 1785, the inmates ‘give thanks for one guinea by the hands of Mr. Easterbrook, bread, beef, coals and 10 shillings worth of salt from an unknown benefactor. Likewise a guinea from Mr. Wm. Hockings. On 22nd January ‘for mutton, beef, potatoes, coals, jackets, shirts, gowns, aprons and stockings

And so it went on through that year, and the years after: for donations of salt fish, beef, bread, potatoes, clothing and occasional money. By the 3 February 1787 ‘the Inmates of Newgate, sixty five in number, many greatly distressed offer thanks for 1 guinea’. Another kind heart was touched in March and on 12th May the insertion was just as pathetic: ‘… the prisoners in Newgate, in great distress, many without friends would be grateful for the smallest donation….’

Mary Kimes and Ann Randall, the ‘Mercury’ escapees, suffered through these lean times. They were brought to court in April 1785, but with local justice unable to agree what should be done with them; they became the subject of correspondence between the Recorder of Bristol and the Home Office. The Secretary of State and the Under-Secretary were both consulted. In September 1786, their names are at the bottom of a list of prisoners in Newgate Gaol with the note ‘to remain under their former sentences,’ but shortly afterwards following two years and three months in limbo Mr. Burke, the Recorder set the two women free. With a small sum of money to maintain themselves on the journey, they were packed off to London in a wagon at Corporation expense. All good news except that as soon as they arrived and parted company, Ann was re-arrested and charged with illegally returning from transportation! Hearing of this dire development Mary, quite naturally, absconded. Mr. Burke was sent for and travelled up from Bristol in December for Ann’s trial. He explained the tale with eloquence, even proudly citing her erstwhile companion Mary Kimes as a success story.

‘I have heard she has got into an honest, sober, way of life,’ he said.

His report swayed the Jury and Ann was found ‘Not Guilty’, but if she thought that put an end to her troubles she was mistaken. There was a very sharp sting to come. The Baron Hotham, the Judge, summed up.

‘You have been acquitted of a capital felony by the evidence of the Recorder of Bristol that you were discharged by lawful authority. The Court is of the opinion that you should not forfeit your life for so being at large, yet you will be in danger of being apprehended and tried for being at large again. The safest way therefore is that you should remain in custody in order to be sent out of the kingdom on your lawful sentence.’

He seems to think he was being kind!

Ann makes no further appearance. Probably taken back to prison or to a hulk in the Thames, and earmarked for the First Fleet, it is quite likely she died before she could be transported.

As to Mary Kimes, despite Mr. Burke’s glowing report, she was soon in trouble again, back at the Old Bailey for the theft of 30 yards of linen valued at thirty shillings from a draper’s shop. James Gibson the shopkeeper followed her outside and made a citizen’s arrest. She went quietly. Her speech in her own defence was incoherent.

She said ‘I never saw it. The gentleman brought it out of me. He said he suspected me some nights’ before. He said he would bring several people to witness that he took it from me. I am innocent.’

Mary was found guilty. She was sentenced to death but held in prison for two years under a temporary respite. Her life of recorded crime had started when she was 24 and apart from a few months on the run, and a free trip to London courtesy of Bristol ratepayers, she had spent six years in prison for two petty offences to which was now added her original sentence of seven years transportation. Aged thirty, too late for the First Fleet, she embarked on the infamous ‘Lady Julian’ on 7th May 1789, where she is likely to have encountered several women she had known in Newgate. She landed safely in Australia where a surprise awaited her.

Within the last few years others had also begun their journey towards Newgate, 1787 and the voyage of the First Fleet.

Joseph Elliott, alias Trimby, came up before magistrates at Shepton Mallet in May 1784. He was accused of highway robbery in company with a boy called John Atwood, who had been creating mayhem. By the age of fourteen, Atwood had already been privately whipped five times, and confined in Bath lock-up seven times. Even allowing for newspaper exaggeration, neither loss of liberty nor corporal punishment had any obvious deterrent effect. His crime with Joseph Elliott sounds fairly ambitious but the haul must have been negligible for both youths were out and about by September. Atwood stayed in the Bath area where a few months later he was in court again, charged with George Gooding for stealing clothes from a washing line. He was presumably locked up as he is absent from the records for two years until 1786 when he turned up in Bristol.

Meanwhile in 1784 Joseph Elliott had made his way to Bristol. On 19 August 1784, a man called John Banks, of 8 Narrow Wine Street was in High Street when he realised he had been relieved of his tobacco pouch. He identified Elliott who had the article in his hand, and was allegedly trying to stuff it into his pocket. Joseph seems to have made no attempt to run away and just stood there waiting to be arrested. Banks marched him to the nearby Newgate gaol, and charged him with theft. The item in question was valued at a risible two shillings.

As a second offender, Elliott, aged 17, was found guilty at the sessions in November and sentenced to seven years transportation.

At the same court John Wisehammer, then about fourteen years old appeared with another boy, Thomas Webber. They had been arrested in April on suspicion of theft from Mr. Samuel Span, a West India Merchant,[3] who lived at 28 Prince Street, a grand house in the Centre of the Old City. Margaret Pritchard, one of the servants said the two gained entry on a pretext, but she noticed something shifty about their manner. After they departed she searched the parlour and counted the spoons. She said four were missing and raised the alarm. The lads were quickly apprehended and taken to the squalor of Newgate where they remained for three months until the Assizes.

No evidence was offered apart from the maid’s accusation and if the spoons had ever gone missing in the first place, nobody knew their present whereabouts. John Wisehammer, recorded in the local press as ‘John Wiseman’ was acquitted. The fate of Thomas Webber is not recorded, but he turned up later on another charge. As to John, guilty or not, suspicion remained, and this counted as a ‘first offence’. He was released on to the streets but from now on would be a marked boy.

John’s name ‘Wisehammer’ or ‘Wisehamer’, suggesting a German origin is exceptionally thinly scattered whether locally or worldwide. In Bristol the family is recorded only four times, all interments. Sarah, buried 22 July 1780 at St James; Elizabeth, 30 March 1787 and Jacob, 11 July 1788 both at Christchurch, but ‘from St Peter’s Hospital’ and finally, Rebecca on 30 April 1792, at St Peter’s. Whether these are adults or children it is impossible to say, as only the names are recorded but it may be that the first two girls were John’s sisters, and Jacob and Rebecca his parents. All except Sarah died in exceptionally poor circumstances – St Peter’s was the Workhouse. If John was a Jew as is alleged in the fictional version of his life, I wonder why his family members were buried in Christian churchyards when there was a Jewish burial ground, dating from 1759, nearby.[4]

Magistrates and citizens alike had become alarmed by the numbers of feral youngsters, mainly male, who were at best a nuisance, and at worst a threat. A concerned correspondent observed in 1785 that ‘a great number of boys without visible means of subsistence are constantly to be met in the street and on the Quays (and) evince to the necessity of some method being adopted of giving these unhappy youths immediate employ and putting them in a line to procure their honest livelihood.’

He suggested some kind of ‘Marine Society to teach them the ways of the sea.’ It was a century before anything came of the idea, much too late for John Wisehammer. Within weeks he was back inside.

On 10 February 1785, he was found guilty of theft, a ball of snuff from a tobacconists’ shop, Messrs. Ricketts and Load in Dolphin Street. He was convicted, sentenced to transportation for seven years and joined Joe Elliott in Newgate to await removal to the hulks. It is tempting to believe that during his sojourn John made the acquaintance of a female thief five or so years his senior who herself was in Newgate at about the same time. Her name was Shuke Milledge.

John Wisehammer and Joe Elliott were among the twenty five passengers including four women convicted in Bristol at various times who have the distinction of being ‘First Fleeters’.

To be continued………..

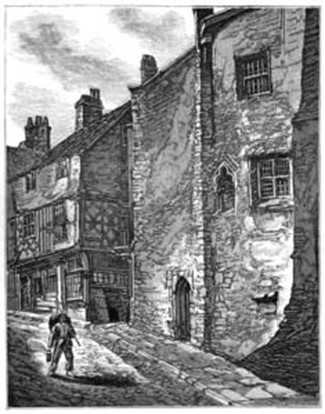

Title picture: Newgate Gaol, Bristol: ‘White above and foul below’, John Howard, prison reformer

[1] Bath Chron, 12.10.1786

[2] See Postscript, p291, Mark Steeds & Roger Ball, ‘From Wulfstan to Colston’ quoting Maxie Lane who called it ‘T-Fish, flat, stiff and briny,’ in the shape of a kite. My mother, born 1906, who was orphaned at nine, hated it. ‘Ugh!’ she said. ‘We never had to have that when our Mum was alive.’ I thought she was saying ‘Tea-fish!’

[3] Shorthand for slave merchant. Quite often Bristol histories of the underclass and slavery overlap. See ‘Centre for Legacies of British Slavery’, https://www.ucl.ac.uk/lbs/person/view/2146645485

[4] Thomas Kenneally, ‘The Playmaker’.

Leave a Comment