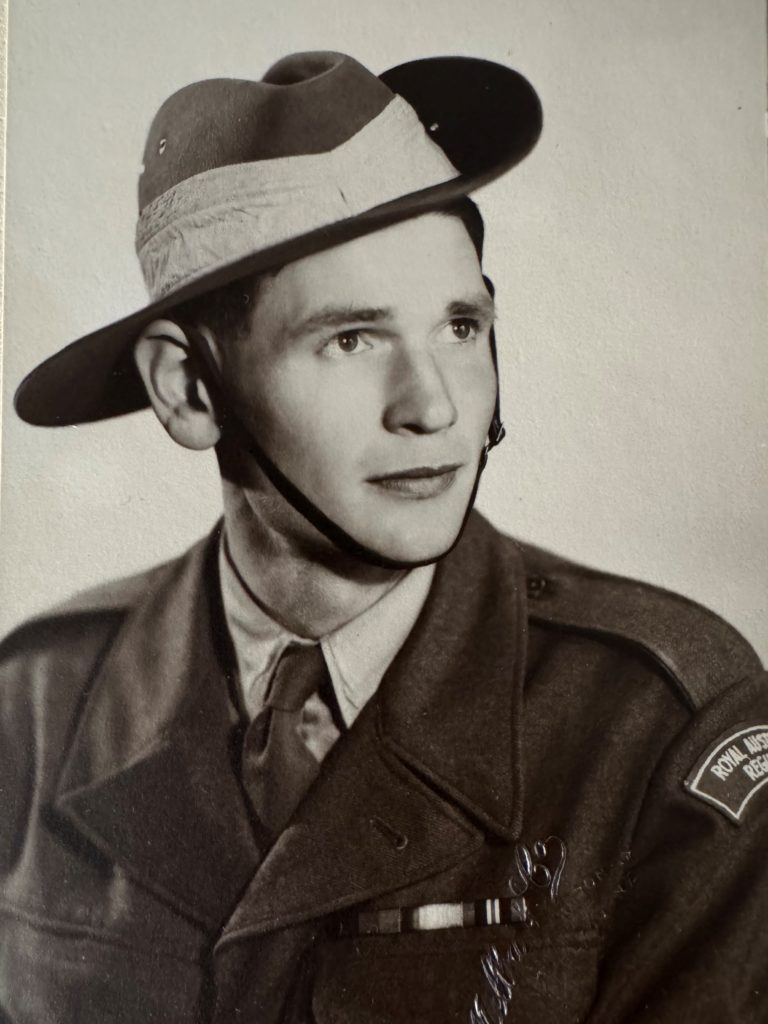

“The solitary survivor of the wreck of the ‘Royal George’ is now living at St George’s, Gloucestershire. His name is Abel Hibbs aged 91. Until lately he was a hale old man but is now bedridden, his only support, the Poor Rate.” (Report, Wells Journal, 3.1.1852)

In the census of 1841 Abel, a labourer, lived alone at Crew’s Hole. At the next census, 1851, he is described “widower, aged 90, born Downend, a lodger at Trubody’s Hill, St George, in the house of William Feltham, a hawker; Relief from Parish, mariner-at-war, and one of the survivors of the ill-fated Royal George”.

It is very unusual to see such additional information on the census form, and it is obvious the census man was very impressed by this ancient mariner. Abel was buried not long afterwards at St George, aged 91, on 24th March 1852.

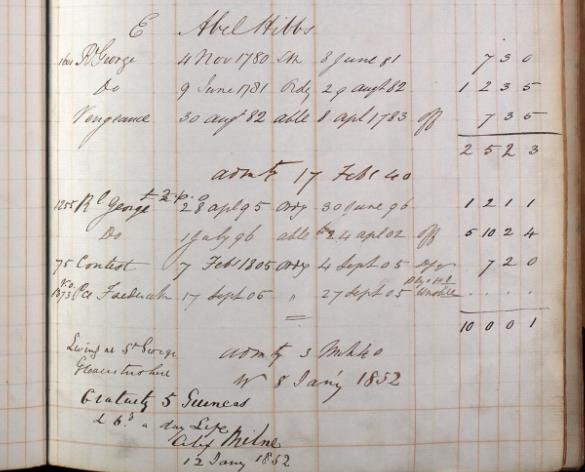

Abel’s service record, like himself, is a remarkable survivor. It shows that he served from 4 November 1780 until 27 September 1805, thus missing Trafalgar by a whisper. He was awarded a gratuity of 5 guineas plus sixpence a day for life, but as this is dated 12 January 1852, he did not live long to reap this belated largesse.

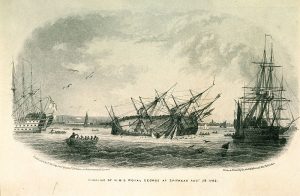

On 29 August 1782, whilst undergoing repairs at Spithead, the ‘Royal George’ began to take on water. She capsized and sank very quickly with a heavy loss of life. It is difficult to state the precise number of people lost, but estimates vary between 900 and 1,200 souls. These included about 300 women and 90 children who were on the ship bidding farewell to their menfolk who were about to embark. Also on board were a variety of visitors and tradespeople, including pedlars hawking trinkets. It is reported only one of the children, a little boy, survived. He lived by clinging on to a sheep which had been on board. The dead included the Rear-Admiral, Richard Klempenfelt and Martin Waghorn, a midshipman, the son and namesake of the ship’s Captain.

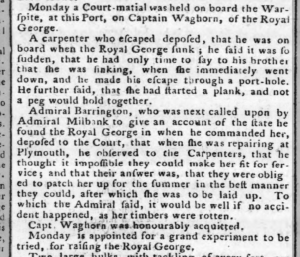

Hampshire Chronicle 16.9.1782

Captain Martin Waghorn was immediately court-martialled and honourably acquitted. It was suggested that some of the ship’s timbers were rotten, which reflected badly on the Navy Board who were responsible for the ship’s condition.

Charles Spalding, the pioneering diver, descended in a diving bell of his own design in 1782 and recovered a dozen or so guns, only to find the Admiralty awarded salvage to another contractor. Spalding died a year later when diving at another wreck site. In 1832, the brothers John and Charles Deane recovered 30 guns before their work was interrupted by local fishermen who asked them to investigate something which was tangling their nets. The culprit proved to be the wreck of the Mary Rose!

See the following websites:

- Port Towns & Urban Cultures

- Royal Museums, Greenwich: ‘An Account of the Loss of the ‘Royal George’ at Spithead, August, 1782′

Blog Comments

N Wright

3rd May 2024 at 10:59 pm

I was amazed to have searched for Abel Hibbs and he popped up here! In 1851 he was living as a lodger in the house with my great,great, great grandfather Edward Feltham and his wife Elizabeth and my great great grandfather Samuel Feltham. I don’t think Abel was related to them but it is a really fascinating side story. You never know what you’ll find on the census!