I became interested in the Peninsular War period through the TV series “Sharpe”. This is predominately a male tale of derring-do but when visiting the National Army Museum in London (www.nam.ac.uk) I discovered the women who followed the drum. I remember my excitement when I first saw the tableau depicting the heroic (and immensely strong) Biddy Skiddy who went to the war in the Peninsula with her soldier husband. When he was injured in the fighting she hoisted her man onto her back and carried him from the battlefield. I have since been fascinated by these incredible women who followed the colours.

Then I found one of our own, Hannah Skuse, (Scuse) of Fishponds, a suburb in the east of the City of Bristol, who went to the war in Spain with her husband Samuel, a rough rider in the 15th Hussars.

She was one of the very few lucky ones, if you can call it luck, for perhaps only about six out of every hundred wives were chosen to accompany their husbands overseas. Selections were made at the drum head resulting in piteous scenes when families were split up. Richard Holmes in “Redcoat” describes one tragic wife, unsuccessful in the ballot, who followed her man to the quayside but died there with their new born child. The soldier was not allowed time to bury them and rarely spoke again. He died in the Peninsula. (,https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Richard_Holmes (military_historian)

These ‘lucky’ wives did most of the menial camp chores – lighting fires, cooking, milking, washing, repairing, sewing, even carrying supplies to the gunners, as well as caring for the casualties, the sick, their children and husbands. The wives received half rations and endured more than their share of privations. Although few were killed in action, hundreds died and many were taken prisoner, as in the desperate retreat to Corunna in 1808. If a husband had the misfortune to die, the danger of being a lone woman often led to a swift remarriage, like the widow of Sergeant Dunn (68th Regt.) who married another sergeant following her husband’s death at the Battle of Salamanca.

In her diary, a Peninsular army wife, Catherine Exley, tells of the births and deaths of children and the hardships she and her husband suffered during his military service, which included a period when they both wrongly thought that the other had died. Life was harsh, cold, hungry, filthy, even without the horror of the aftermath of bloody battles.

(See “I’ll be Reet” – “Follow the Drum – Women’s Stories from the Regiment’ at Cumbria’s Museum of Military Life.” https://mlwegener.wordpress.com/tag/biddy-skiddy/ and “Following the Drum: British Women in the Peninsular War”, Sheila Simonson, 1981; Catherine Exley’s Diary: the life and times of an army wife in the Peninsular War. Kenilworth: Takeway (Publishing). ISBN 978-0-9563847-9-9. Richard Woodhead, Rebecca Probert, 2014;

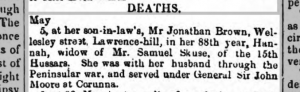

Hannah Skuse’s exact date of birth is not known, but she stated she was born in Fishponds, and lived in Bristol after her husband left the army. From her newspaper obituary we know she served with him in the Peninsula. (Cheltenham Mercury, 18 May 1867):

Her marriage to Samuel Skuse has not been traced.

No record of Samuel’s army career survives except for a one line entry showing he received a medal for his part in the cavalry charge at the Battle of Sahagun on 21 December 1808. www.skuce.com.genealogy/military.html

Sahagun was occupied by a French cavalry force. On a bitterly cold December night, Lord Paget ordered the 10th Hussars to move through the town whilst he made a sweep around the perimeter with the 15th Hussars, (which included Samuel Skuse), to trap the French inside.

Unfortunately General John Slade was tardy moving off the 10th Hussars and the French, realising the British were nearby withdrew from Sahagun to the east and left the town unmolested.

In the dawn light the French regiments, caught sight of the 15th Hussars to the south and formed up in two lines with the 1st Provisional Chasseurs in front and the 8th Dragoons at the back. The French cavalry received the charge of the British Hussars whilst stationary and tried to halt them with carbine fire.

The 15th Hussars charged, over about 400 yards (370 m) of snowy, frozen ground, shouting “Emsdorf and Victory!” It was so cold they wore their pelisses, (the ornamental fur-trimmed coat which was generally slung over one shoulder for show.)

Eyewitnesses spoke of numbed hands hardly able to grasp reins and sabres. The impact when the Hussars met the Chasseurs was terrible, as one British officer recorded:

“Horses and men were overthrown and a shriek of terror, intermixed with oaths, groans and prayers for mercy issued from the whole extent of their front.”

The impetus of the British Hussars carried them through the ranks of the Chasseurs and into those of the Dragoons behind. The French force was broken, and withdrew eastwards with the British in pursuit. Many French cavalrymen (though the Chasseurs were largely of German origin) were taken prisoner at very little cost to the 15th Hussars. Two French lieutenant colonels were captured and the Chasseurs, which lost many men, killed and captured, ceased to exist as a viable regiment. The 10th Hussars arrived during the pursuit, but in the melee were initially mistaken for French cavalry. (The horror of so-called “Friendly Fire”.) This caused the 15th Hussars to break off their pursuit to re-form, ending the action.

When the European War against Napoleon came to an end with the Allied victory at Waterloo in 1815, Samuel Skuse like many soldiers, was discharged by the army as “surplus to requirement”.

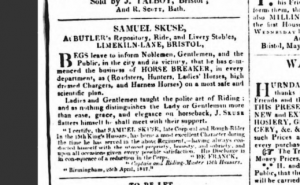

He set up in Bristol as a Horse Breaker and Riding Instructor at a yard in Lime Kiln Lane and advertised his new venture in the Bristol Mirror of 17 May 1817 with a reference from an old comrade, Captain De Franck, riding master of the 15th Hussars:

“I certify that SAMUEL SKUSE late corporal and rough rider of the 15th King’s Hussars has borne a most excellent Character during the time he has served with the above regiment having always conducted himself with the utmost propriety, honesty and sobriety and upon all occasions given the utmost satisfaction. His discharge was due to a reduction in the Corps.”

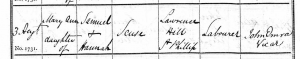

We know that Samuel and Hannah were in Bristol by 1817 (see above advertisement) but the first record of them having children is when their son George was christened on 15 July 1821. His brother Aaron is recorded for 13 November 1825. They also had two daughters, Mary Ann, baptised at St George 3 August 1823 and Sarah at St Philip & St Jacob, 4 May 1828, aged three weeks.

Whether Hannah had given birth to previous children who were born and died during the war is not known.

A child, a young girl, is depicted trudging behind her parents in the Biddy Skiddy tableau.

The Skuse family appears on Bristol censuses every decade from 1841.

At this time, few people knew their exact date of birth but when the census collector called Hannah Skuse was fairly consistent.

1841: Birthdate ca 1785-1791. In 1841 living at Gibbs Yard, Lawrence Hill, Bristol, she was “aged 50”, born “in this county” – i.e. Gloucestershire, with husband Samuel, “aged 60”, and children, Mary, 18 (1823), Aaron, 16 (1825), George, 15, (1826) and Sarah, 14, (1827).

The date suggests that Hannah was born about 1791 – but for this census a peculiar system was adopted: Census takers were instructed to record the exact ages of children but to round the ages of those older than 15 down to a lower multiple of 5. For example, a 59-year-old person would be listed as 55. This caused confusion of course, but we may assume from later evidence that Hannah was born between 1785 and 1791. It seems likely that the discrepancy between the ages given for George Skuse is down to this bizarre census system.

1851: Birthdate 1786. In 1851, the Batch, Lawrence Hill. Hannah was 65, “a fishwoman” and Sam, 69, “a pauper, formerly labourer”, so much for a grateful country. Two adult children were at home, Aaron, a 25 year old labourer, and Sarah, aged 22.

Hannah was widowed in 1856 when Samuel Skuse, the old soldier, was buried aged 73 on 29 July 1856 at Holy Trinity, St Philips, Bristol. I have found no newspaper obituary for him. After Sam’s death Hannah lived with her daughter Sarah who was married a year after the census (in Bristol in 1852) to Jonathan W. Brown. (NB: Sarah is listed as “Shute” on “Find my

Past” https://search.findmypast.co.uk/search .)

1861: Birthdate 1785: at Wellesley Street, St Philip & St Jacobs, Hannah was with her son-in-law Jonathan William Brown, a brassfounder, (born St Philips in 1829), his wife Sarah and five children. She is listed as “Ann” Skuse, aged 76, mother-in-law, widow, born Fishponds. Her stories must have entertained and enthralled the Brown children!

1867: Birthdate 1783. Hannah’s death was registered at Clifton aged 84, showing the same consistency of date but the newspaper obituary in the Cheltenham Mercury of 18 May 1867, (see above) went slightly over the top:

“May 5th at her son-in-law’s, Mr Jonathan BROWN, Wellesley Street, Lawrence Hill, in her 88th year, Hannah, widow of Mr Samuel Skuse of the 15th Hussars. She was with her husband through the Peninsular War and served under Sir John Moore at Corunna.”

—————————————————————————————

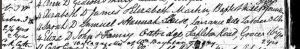

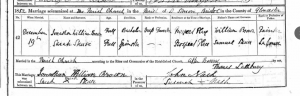

- The marriage below which took place in 1792 at St James Church in Bristol belongs to an earlier couple.

Leave a Comment