Going off in tangents, so I’ve been told, is a symptom of ADHD. A few days ago, (January 2024) I was merrily researching steamships to complete another project, “The Life and Sea-Faring Times of Richard Hendy, Mariner”, for which, see elsewhere on this blog. Richard, now 97, spent much of his lifetime at sea. One of his many ships was the mv. Salacia.

There is no reason to believe that Richard was aboard Salacia in 1959, when it had been adapted to carry livestock, mostly ponies, across the Atlantic, something I thought my friend would have remembered but he had said nothing about it. The newspaper reports of the system were matter of fact, not graphic, but nevertheless I read them with contemporary distaste.

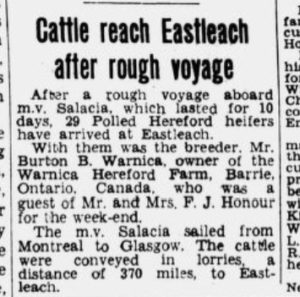

A particular cargo, referring not to the transport of horses but cattle, poked me sharply, metaphorically, in my one good eye. A short paragraph stated that a Mr Burton V. Warnica, (whose name suggests a likely part for Groucho Marx in the film version, cigar obligatory), a Canadian cattle breeder, had recently crossed the ocean from Montreal to Scotland in Salacia, a very rough ten-day voyage. Mr Warnica had brought with him twenty-nine polled heifers, (born without horns), which he had bred himself. He and his young ladies must have been more than happy to skip down the gangplank in Glasgow, but the ordeal was not yet over. They had to endure another 370 miles, by train, to their eventual destination, the green fields of Gloucestershire, which is where we’ll leave them, man and beasts for the time being.

Polled Hereford Cows and Calves. (Copyright Greenview Farms)

Come with me on a journey back to 1955. One of my former bosses, of nearly seven decades ago, a Miss Reader, thin as a piece of string, wispy grey bun and all, was wont to say to my 18-year-old self, not unkindly, with a hint of cockney, “All very interesting, I’m sure,” (which she pronounced with two syllables, “Shoo-er”), “but now, perhaps we can get on with our work?”

You may be thinking the same but bear with me. I was working in London at the Overseas League. Miss Reader was one of the very few “good” office supervisors I encountered over a host of jobs through many wandering years, a horse whisperer, who knew the way to tame a mustang was with humour and patience. She has nothing to do with the main thrust of this piece, except to evoke a time and space, and in flashback I can see again her amused half-smile, as she tartly cut off the gush of my latest enthusiasm.

At the time I lived with my auntie, my mother’s sister, in a one-bed rented top floor flat at Horn Lane, Acton. Pem (real name Emily) had been in London throughout the blitz, been bombed out twice, and had recently upgraded from a bedsit and a gas ring to this current luxury. Her ghost has visited this blog already, more than once. With little spare cash to go anywhere which cost, and not much distraction unless there was something good “on the wireless”, people talked a great deal to each other. Like the first Homo Sapiens sitting round their campfires, we told stories. Pem’s usually began “When I was a little girl, no higher than a penn’orth of coppers…..” thus starting me on a long road which ultimately led to today. Pem’s tales were all about her family, the Honours of Otmoor, who from promising beginnings fell on hard times.

I was hooked. Though not much more than a child, I knew about history. The big stuff. Pem said, confidently, without evidence, that the Honours “must have been” long bowmen at Agincourt. I lapped it up. Done up in Lincoln green, like Richard Todd as Robin Hood at the pictures, this was the nearest we had to verify the existence of “ordinary people”. Like us.

From the time I was seven, I had proudly owned a library card. Museums and libraries were my natural habitat. I would choose either one, even now, over enduring small talk at a party. After Pem stoked the fire, I started rudimentary research in the library with telephone directories. Pem airily dismissed those with the audacity to spell themselves “Honor”, or any other alternative, unaware that our historical selves were at the mercy of their literate “betters”, vicar, squire, doctor, the men in charge who decided how we should be styled. With squiggles on paper meaningless to us homespuns, the forms stuck. Those Pem deemed worthy congregated mostly in Oxfordshire or Berkshire, (“Nothing wrong with Berkshire!” remarked “the Queen” in the recent final episode of “The Crown”.) There was only one Honour in Gloucestershire. I wrote to the address on a whim, probably, because Gloucestershire was my county, the one I called I called home.

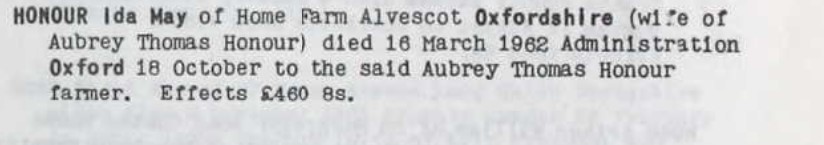

A reply came quickly, from a woman, who said something like “we farm over two hundred acres here”, it may even have been “two thousand” for all I remember. I didn’t believe they were ours for a minute. Too high above our station, but my correspondent was chatty enough, and included a few family Christian names, one of which was Aubrey.

Unlike me, Pem was unfazed. “Hmmm!” she said, as if she expected this all along. “Of course. It’s him. Aubrey. I know him. He was one of our cousins. Ettie and I used to tease him. We said he had a girls’ name. Audrey.”

Ettie was her late sister, one year her senior.

Sadly, that was all Pem could remember of the time she met Aubrey Honour.

I had reservations about this minor recall, when she could not have been more than about four, but I would have followed up the letter had not fate intervened. Somebody told the landlord that Pem was sub-letting, which was against the rules of her lease. I had to move out. Hurriedly. I found a cubicle in an LCC hostel in Fitzroy Street. Though it was workhouse-grim, it had a few things going for it. For one, it was “up west”. Pem was no longer on my case with her deathly warnings “This is London, my girl, not Bristol.” I could walk to work through Soho, information I kept to myself. Pem shared my dad’s ominous views on “white slave traffickers”. Give me a break. I was adventurous, but not stupid. I had the sense never venture down an alley into the “opium den” they feared was waiting there to enfold me. I spent the odd evening musing over one espresso in the coffee-bar at the top of Tottenham Court Road where a handsome bloke played gipsy music on a guitar, but more often I would be just round the corner from my new HQ, savouring the finest buckshee entertainment in the world at the British Museum. I spent hours there. I forsook the Honours for a new craze, Egyptology. My time among the mummies was interrupted only by playing sailors once a week with the GNTC at Kilburn, or, at weekends, if I could afford it, failing to learn to sail on the river Blackwater in Essex. I didn’t remain in W1 all that long. My Mum came and took me home after I had an emergency appendectomy. She was very cross and said I was “living in reduced circumstances.” Torrents of water ran under the bridge until……

……. two decades later family history caught up with me. A novice researcher, I found so many Honours in the Otmoor “five towns” that you could drown under the weight. I concentrated on the direct line and didn’t bother with “the sisters and the cousins and the aunts” who were reckoned up in dozens (as in Gilbert & Sullivan.) I never gave a thought to Aubrey, until now.

It was like turning a corner and an old mate from foreign parts jumps out at you, but it was not Aubrey, but a Mr & Mrs F.J. Honour who leapt from the Bristol Evening Post, of 3 November 1959. The cutting suggests that everybody knew who this Mr & Mrs Honour were.

It was like turning a corner and an old mate from foreign parts jumps out at you, but it was not Aubrey, but a Mr & Mrs F.J. Honour who leapt from the Bristol Evening Post, of 3 November 1959. The cutting suggests that everybody knew who this Mr & Mrs Honour were.

Were they relatives of Aubrey? Was it from Eastleach that the letter came from all those years ago?

Once again, let’s go “back in the day”, it’s now 1975, when our infants were, well, still infants. Norman, who had not then been reborn as George, (not religiously), would sacrifice golf on one of his precious days off and give me a treat. He would take “Rent-a-Riot”, my brother Colin’s collective name for them, off to the Zoo. I would get an early train for Oxford, (change at Didcot), tear round to the august premises of the Bodleian Library where a whole trolley load of documents, ordered in advance, awaited my arrival at a reserved desk. For the next ten hours, I kid you not, I riffled through them, writing furiously in pencil, unable to spare even a minute for the frivolity of taking on fuel. Even the porters who patiently replenished my stocks from the vaults were flagging by closing time when I headed back to Oxford railway station at speed, arriving breathless as the train whooshed onto the platform. Only when seated did I realise I was starving, tear into my sandwiches and slake my thirst with swigs from a bottle of Tizer. Once home, both of us, husband, and wife, slumped down exhausted, though he had better luck than I ever did at getting our boisterous trio into bed.

On one occasion, Colin and I descended on Charlton-on-Otmoor, though bumping along in his aged Land Rover, was even less luxurious than the train. The Rector, himself a keen genealogist, (the original parish registers were still in the church), gave us two hand-written charts with the names of our forebears, because, he said, the Honour family, were among “the oldest” in the village, but “One side refuses to believe they are anything to do with the other. And vice-versa. Nonsense of course. I’m very pleased to meet you.” He paused the monologue before adding, “You owe me some money.” This was not unusual. Vicars usually requested a reasonable donation. He took a sheet of paper from a drawer. “I reckon,” he said, “that with compound interest, it amounts to…….” and named an astronomical sum. Seeing us completely taken aback, he explained. One of the Honours, Job Honour of Murcott, in something like 1679, borrowed money from the church “and NEVER paid it back.” Luckily, the Rev. was joking.

The bulk of my maternal history stems from the crazed notes taken down at these flying visits. All done by hand. In the early gestation of personal technology, which we now take for granted, my only experience of “Computer stuff” came on batches of green chequered paper, with reams of figures, printed on perforated sheets which Colin sent us to use for scrap. I still turn up pieces of it to this day.

George and I also drove several times to Otmoor, the last time in 1992, with my Mum, Florence, otherwise Flo, then a robust 86. (She was 10 years younger than Pem.) This was “a pilgrimage”, first to Ripley, Surrey where she was delighted to find Newark Lane, where she lived before she was ten, the school where she and her little brother Harry were pupils and the churchyard where her mother Sarah, and two of their siblings were buried. The inscription on every gravestone had been obliterated by weather. We took in Eversley, another family landmark, before going to the “five towns”. Mum walked down the aisle in the church where her parents had walked on their wedding day. She gave a wistful smile. “Fancy,” she said. “Me. Their little girl. All those things that came after. All the things they didn’t know.” She was the definition of stoical. She never cried. If we ever asked why, she would answer “I did all my crying a long time ago.” She liked a quiet life after so much hardship. She made up for it with love.

Now I come back to Aubrey Honour. He was born in 1890. I’m surmising that he would not have been over thrilled at being taunted by a couple of little girls five or six years his junior. I suspect the family gathering took place at Hampstead Norris, sometime around 1901, but before 1906, the year Mum was born at Hook, in Hampshire. Pem always referred to these brief halcyon years as their father Levi’s “heyday”. Before it all went wrong. The loss of Townsend Farm, his pride, their livelihood, disgrace, penury, grief, (they lost three children) moonlight flits, the death of Sarah, wife and mother, worn out at forty-nine…….

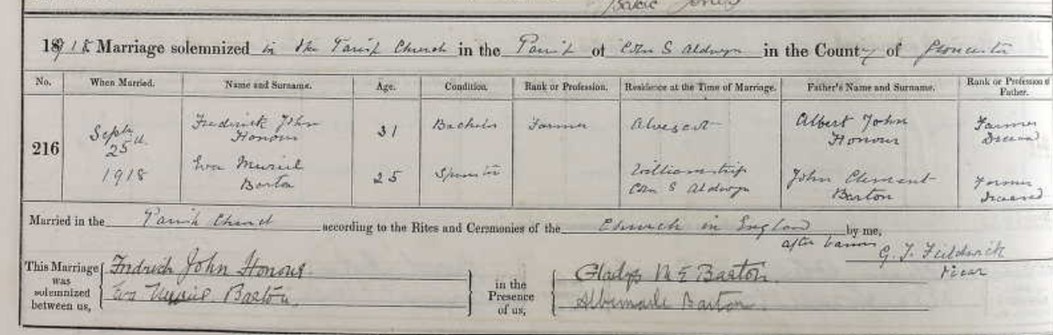

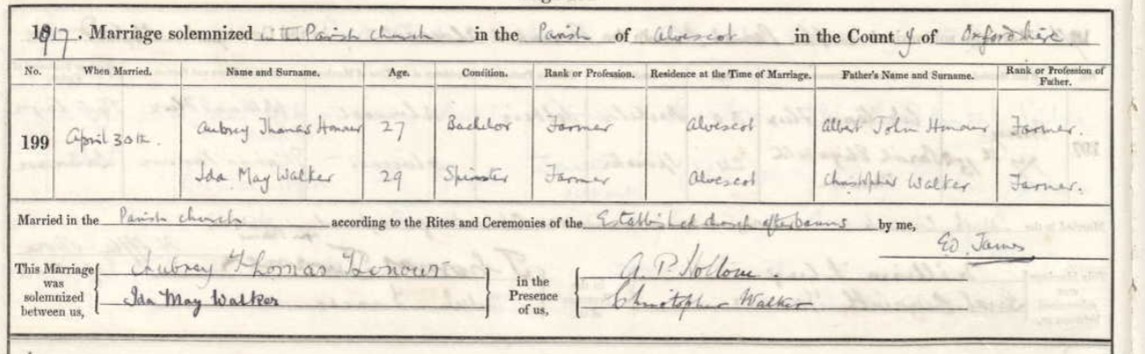

Aubrey was christened in 1893, unusually for the Honours, “in chapel”, in Oxford town, in a job lot with a sister and three brothers, one of whom Frederick John was born in 1888. “F.J.” of Eastleach! His father, Albert John, was first cousin to Pem’s and Flo’s dad, Levi.

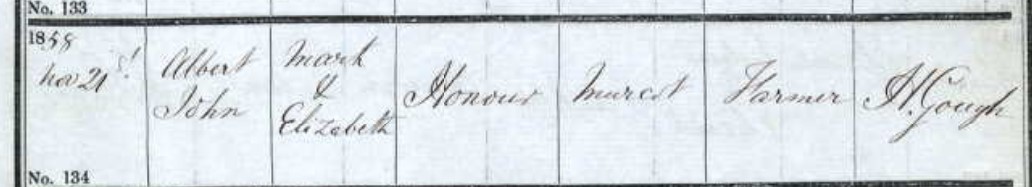

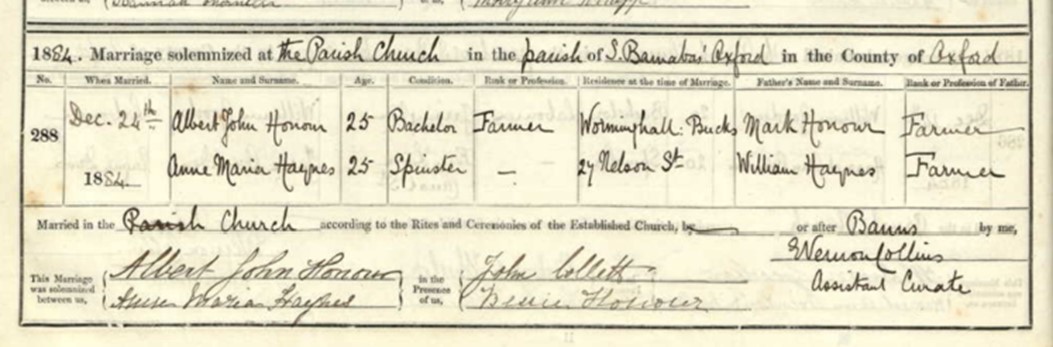

We are descended from three brothers of a previous generation, John, born 1818, Thomas, in 1828, and Mark, born in 1832, who were by no means the entire progeny of “Job Honour of Murcott”, (the first name in our Family Bible, of a later vintage than Job the debtor) and his wife Sarah, nee Hoare. John and Thomas were my great-great grandfathers: John’s daughter Sarah married Thomas’ son Levi, which explains “Honour thy Father and thy Mother”, the title I chose for the family saga. Mark, their younger brother begat Albert John, more often known by his second Christian name, whose two elder sons were Frederick John, born 1888 and Aubrey Thomas in 1890.

All the men were farmers, some more successful than others. It is quite feasible that cousins should go visiting. Pem’s memory was as sound as mine, but who visited whom is another matter, whether they came to Hampstead Norris or the other way round. Either way, rather than showing off, I hope that Levi was not tapping his cousin for a loan.

On a Sunday in 1974 we were at Hampstead Norris (nodding to ‘ye olde’ now calls itself ‘Norreys’. Posher?) Caroline was six, Celia, 5, and Kevin, 4. I guess it was Spring, my favourite time of the year, when I come out of hibernation, though a chill in the air is suggested by their garb. The girls are wearing leather coats with fur trimming, all faux, Caroline’s blue, Celia’s light tan. Kevin is in a brown corduroy suit with shirt and tie! Probably George and I were equally formally attired. Strange to look on a period when you still dressed up to go out. Back in 1896 Levi has his thumb tucked into the top pocket of his waistcoat in a pose Pem called “I am the Lord of all I Survey”. Sarah, wearing a long dress with a frill across the bosom is in the middle with the babies sitting on the grass, Ettie, demure, serious, with Pem looking down, face obscured. The house is still recognisable though with a different porch and an extra chimney pot! I knocked on the door, and the current owner took me on a tour of the house. George stayed outside with the children, mortified

Grainy photos of then and a more recent then (about 50 years ago)

Cogges Farm, at Witney, now a community history project and tourist attraction.

There was more than one Aubrey Honour, (wouldn’t you know?) but I’ve have been able to discount the others. In 1891 Frederick John and Aubrey, were living with their parents Albert John (farmer and dealer) and Annie, at Cogges Farm near Witney, where both boys were born. The family lived at Cogges at least c1886-1893, the date their last child, Willie Dean Honour, was born but by 1901 the family was at “The Farm House”, in nearby Lew. They were still at Home Farm, Witney in 1911 where Aubrey remained for the rest of his life. By 1918, F.J. married Eva Barton at Coln St Aldwyn, Gloucestershire.

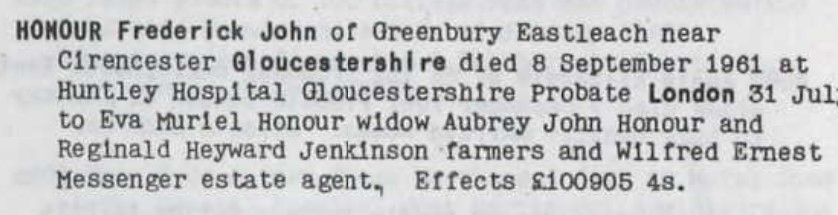

In the census of 1921, they lived at Eastleach, when F.J. described was a “farmer and dealer”. Between 1929 and 1935, he made three foreign trips, two to Gibraltar and one to Marseilles in France, probably on business, seemingly alone.

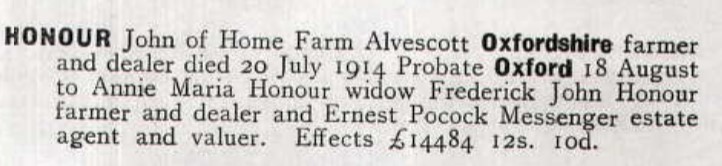

Frederick John Honour died on 8 September 1961 at Eastleach, leaving £100,905 and four shillings.

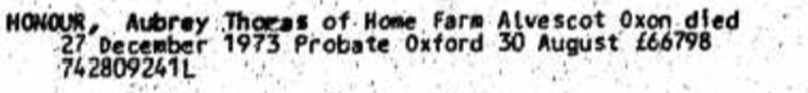

Aubrey Thomas Honour, of Home Farm, Alvescot, near Witney, died 27 December 1972, leaving £66,798.

Their father, Albert John Honour, died 20 July 1914 at Home Farm, Alvescot leaving £14,484 12s 10d. I need hardly say that these cousins were well off.

My grandfather, Albert John’s first cousin Levi, by then a hay trusser, dropped dead aged 69, at a bus stop in Soundwell Road, Kingswood, Bristol in 1937 when I was a few months old. He had a few pence in his pocket, and a small card, “a text” of the kind given out at “Sunday School”. It read “Come unto Me all ye who are heavy laden, and I will give you rest.”

Leave a Comment