This is one of those blogs which starts off with one subject and lands up with another, connected, but completely unexpected.

Whilst I was drawn to the desolate beauty of the island, surrounded by a glittering sea, it was the industrial archeology which aroused my greatest interest.

Regrettably at the time of our April visit, the historical workings of the slate quarry were closed to visitors, though the current operation (the quarry reopened in the 1990s) could be seen in the valley below.

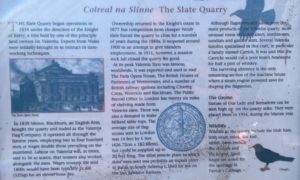

The notice board provided much of the information necessary – the slate quarry began operations in 1816, under the auspices of the Knight of Kerry, the principal landowner in the district. (This august person was then Sir Maurice Fitzgerald, the 18th holder of the hereditary Hiberno-Norman title which dates from the 13th century.) Though slate had been used as housing on the island for years, full industrialisation brought with it the necessity for experts in the field.  More men of Celtic origin, were drafted in: slate miners from Wales, rather than the Cornishmen of Allihies (!) I didn’t pay much heed to “the arrival of the English firm of Messrs Blackburn which took over operations in 1839”, believing that the information was possibly too slight to avoid a long research slog. Allegedly there were 200-400 men employed at wages double those paid on the mainland. In the mid-1800s the rate was 2s 6d (12½ pence) for an eleven-hour day. Labour on Valentia was at times said to be so scarce that women also worked alongside the men. Competition from Welsh slate forced the quarry to close during the 1880s. It reopened around 1900, as an attempt to give the Islanders employment, but in 1911 it closed due to a massive rock fall.

More men of Celtic origin, were drafted in: slate miners from Wales, rather than the Cornishmen of Allihies (!) I didn’t pay much heed to “the arrival of the English firm of Messrs Blackburn which took over operations in 1839”, believing that the information was possibly too slight to avoid a long research slog. Allegedly there were 200-400 men employed at wages double those paid on the mainland. In the mid-1800s the rate was 2s 6d (12½ pence) for an eleven-hour day. Labour on Valentia was at times said to be so scarce that women also worked alongside the men. Competition from Welsh slate forced the quarry to close during the 1880s. It reopened around 1900, as an attempt to give the Islanders employment, but in 1911 it closed due to a massive rock fall.

At its peak, Valentia slate was exported worldwide and used for the roof of the Paris Opera House, the Houses of Parliament at Westminster, and railway stations, Charing Cross, Waterloo and Blackfriars. The London Record Office has 26 miles of shelving made from Valentia state (!), which was also in demand for billiard tables. The average length of slates exported were 14 feet 6 inches but could go up to 20 feet. Flagstones were the main product, but also included altars, tombstones, sundials and garden seats.

The chimney, the only remaining section of the Machine House, with the other relic as before.

“Several Valentia families specialised in monumental masonry; one family named Carrick ‘would cut a poor man’s headstone for half a pint of whiskey.’”

The picture left is courtesy of the authors of “Valentia Slate, County Kerry: a heritage stone,” , a detailed scholarly account from which I have taken the next abstract, found after we returned home:

“Valentia Slate (Devonian) from Valentia Island in southwest Ireland, is a distinctive dimension stone. A largely purple coloured siltstone, it was affected by low-grade metamorphism and has a well-developed cleavage giving it a slaty fabric. Quarried from 1816 onwards, the Valentia Slate Formation yielded very large slabs that were utilised for building and for a wide range of domestic and decorative purposes, in Ireland, England and further abroad. The stone saw lesser use as roofing slate. Associated with the quarry were two sawing and finishing mills located on site and close by, and both finished and rough blocks were exported from a purpose-built pier. Extraction reached its peak in the 1830s to 1870s but subsequently declined due to competition from Wales, before eventually ceasing in 1911. Revival in the 1990s and recent investment has resulted in the provision of this quality stone to widespread markets where it is used for a variety of conservation, decorative and construction purposes.

Valentia Slate and the quarry where it is extracted are both of significant heritage value.”

Knightstown, Valentia Island, a fish curing centre, c1870, in the background the Slate Yard with its towering chimney. (Kevin took the photograph from the board in the harbour. The original is part of the “Eblana Collection NLI.” With thanks.)

The crowd of locals (enlarged) interested me most, particularly the women. The one in front seems to be barefoot. Writing this, I could get a whiff of the fish. Really. It invaded the room where I write.

Valentia with the Lighthouse in the distance.

Photo of a watercolour of the bay and slate works.

Searching for the “Bristol connection”, I mulled over another interest, the shipping trade between the Bristol Channel and Ireland, almost certain that Valentia slate must have sometime been unloaded at Bristol Docks. A snap check of newspapers provided dividends by way of the “Imports from Ireland” columns, (Western Daily Press, 1867 – 78) which confirmed that Valentia Slate had indeed come regularly into our docks, about 110 tons at a time, aboard ships called “Zouave” and “Gleaner” and probably others. One-liners of arrivals and departures of sundry cargo vessels becomes repetitive after a time, so via reading the ‘heritage stone’ document and the confirmation of a tenuous Bristol connection, I was prepared to leave the slate mines forever………. but I reckoned without the intervention of fate.

At the time of writing, I received an email from an occasional ‘follower’ and fellow local history enthusiast telling me of her discovery of suffragettes active in 19th century Bitton, Gloucestershire, the home parish of our, hers and my, ancestors. I was not required to do anything except read the articles she attached, and I gobbled them up with enthusiasm, but being me, and ADHD, I forgot the main task and eagerly put ‘suffragette’ and ‘Bristol’ into the newspaper “finding box”. It must be something to do with the fairies on Valentia, for this was the second time when writing the account of our Day 6, I could not believe what I was seeing. An obituary in the Horfield & Bishopston Record & Montpelier Free Press for 17 January 1903 reads:

“Miss Helen Blackburn, whose death is reported acted as secretary (and afterwards honorary secretary) for many years of the central committee for women’s suffrage in London having been at an earlier period secretary of the Bristol and West of England Suffrage Society. For a number of years she edited The Englishwoman’s Review, a quarterly publication recording the course of various women’s activities at home, in the Colonies, and abroad.

“The deceased was born in Ireland and spent her early youth at Valentia where her father managed some slate quarries for the Knight of Kerry. Her father possessed gifts as an inventor and was driving about Regent’s Park in a horseless carriage of his own construction more than twenty years before the appearance of the modern motor car.”

Now, my thoughts were racing. “Come on……. pull the other one! Blackburn? The same, surely?” Yep. Look back at the notice board. Helen’s father was not just a “Firm” but a man, by profession a Civil Engineer, who managed the slate works on Valentia. As to Helen, who I had never heard of before, she was famous in her time, and her name is among the 59 women and four men who supported Women’s Suffrage engraved on the plinth of the statue of Millicent Fawcett, the Suffragist leader, in Parliament Square in London. What a Bristol connection!

“O Tiger-lily!” said Alice, addressing herself to one that was waving itself gracefully about in the wind, “I wish you could talk!” “We can talk,” said the Tiger-lily, “when there’s anybody worth talking to.”

(The Garden of Live Flowers, Sir John Tenniel, 1871. Wood engraving by Dalziel, for Chapter 2 of Lewis Carroll’s “Through the Looking Glass”).

(In 2000, student assistants from the University Scholars Program, University of Singapore, scanned this image and added text under the supervision of George P. Landow. I am grateful for their generous gift in allowing it to be used for scholarly purposes only, without prior permission.)

But there was more to come, where it is easy to picture the young Helen Blackburn, not at all hampered by Victorian strictures, scampering about on her wild island, avoiding rabbit holes, hair streaming like Tenniel’s Alice; very advanced for eleven years of age, and curiouser and curiouser, she was collecting plant specimens.

(In 2000, student assistants from the University Scholars Program, University of Singapore, scanned this image and added text under the supervision of George P. Landow. I am grateful for their generous gift in allowing it to be used for scholarly purposes only, without prior permission.)

A report, 22 November 1853, in Sanders’ Newsletter, Dublin, concerns a meeting of the Dublin Natural History Society:

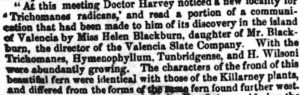

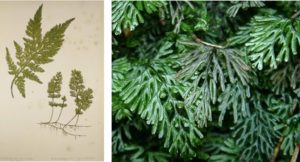

“At this meeting Doctor Harvey noticed a new locality for ‘Trichomanes radicans’ and read a portion of a communication that had been made to him of its discovery in the island of Valentia by Miss Helen Blackburn, daughter of Mr Blackburn, the director of the Valentia Slate Company. With the Trichomanes, Hymenophlylum Tunbridgense and H. Wilsoni, abundantly growing. The characters of the frond of this beautiful fern were identical with those of the Killarney plants and differed from the forms of the same fern found further west……[illegible] ….….it was extremely interesting to hear of Trichomanes and Hymenophyllum Tunbridgense being found in so bleak and unsheltered a position as Valentia Island presented for the growth of such ferns. Mr Andrews had met Trichomanes on Mount Eagle, west of Dingle, a rocky and barren locality. No doubt at one period trees flourished at Mount Eagle and Valentia and these beautiful ferns may have been frequent in those places. The Hon Dayrolles de Moleyns had also discovered Trichomanes in a locality near Dingle.”

“At this meeting Doctor Harvey noticed a new locality for ‘Trichomanes radicans’ and read a portion of a communication that had been made to him of its discovery in the island of Valentia by Miss Helen Blackburn, daughter of Mr Blackburn, the director of the Valentia Slate Company. With the Trichomanes, Hymenophlylum Tunbridgense and H. Wilsoni, abundantly growing. The characters of the frond of this beautiful fern were identical with those of the Killarney plants and differed from the forms of the same fern found further west……[illegible] ….….it was extremely interesting to hear of Trichomanes and Hymenophyllum Tunbridgense being found in so bleak and unsheltered a position as Valentia Island presented for the growth of such ferns. Mr Andrews had met Trichomanes on Mount Eagle, west of Dingle, a rocky and barren locality. No doubt at one period trees flourished at Mount Eagle and Valentia and these beautiful ferns may have been frequent in those places. The Hon Dayrolles de Moleyns had also discovered Trichomanes in a locality near Dingle.”

I did not make up “the Bristle fern” Honest. Only Bristolians will understand the meaning. This is the cosmic joker at work again.

Trichomanes Radicans: The Bristle Fern

Unfortunately, your scribe’s scientific studies at school went only as far as Year 3, General Science, at which point she was shunted off to Domestic Studies, for which she was even less suited. This was the fate of girls in her day, unless brilliant.

All matters greenery being the province of (yet another) branch of Brutus Tours Ltd, I defer here to the learned Algernon, a Renaissance Man, for comment. kevin@willowsolutions.info

For more about HELEN BLACKBURN , & full references, see BRISTOL WOMEN, elsewhere in this blog.

ooOOoo

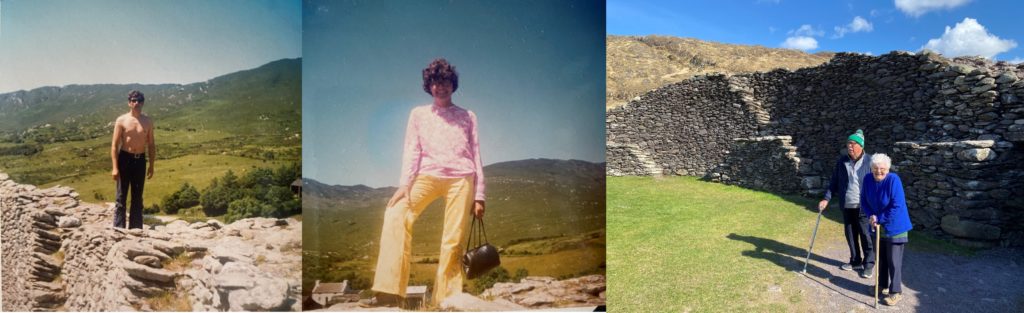

PS. The day finished with a nostalgic trip to the Iron Age Staigue Fort –

For a brilliant account, see The Roaring Water Journal to which I am indebted for the photos.

Then, 1973: George barechested and me in my dashling YELLOW slacks! And NOW, 2025…..

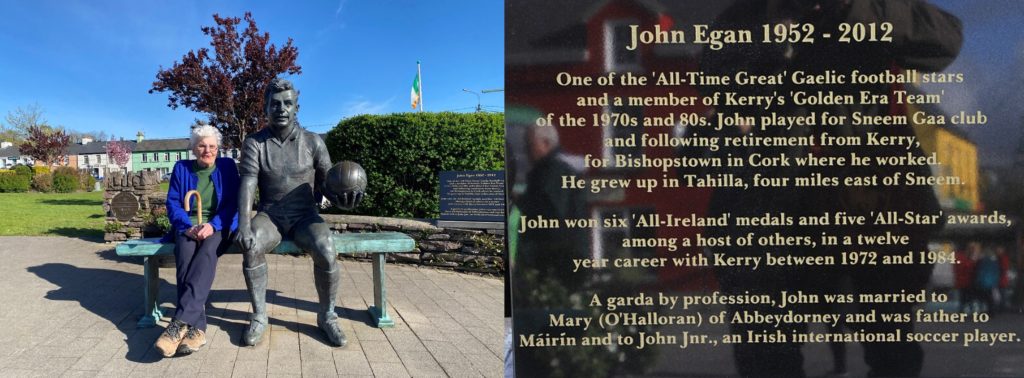

……followed by a welcome sit down at Sneem with the ‘All-Time Great’ Gaelic football player, John Egan. I always did like a nice young man.

Then on to our hotel, back where we started. Live music was advertised. The place was full, so we ate dinner in a cupboard off the main tranche. We expected a fiddle, but the flute music played by two women, was a bit samey. Probably just as well. We were quite tired, particularly the oldies. So up the wooden hill to Bedfordshire, and then onwards our last day………

Leave a Comment