“Going to Barbados” (a euphemism for being “under the influence”.) Benjamin Franklin, 1737. (attrib.) [1]

“Barbados is the other place where I like to be.” Cliff Richard.

Introduction

This is the sequel to “Pamela Pillinger” in the series “My Pillinger Women” and her story should be read first. I expected the ancestral trail of C.W.B., Pamela’s husband to be brief. Wrong. It turned into a saga, an unexpected journey through time and space from Bristol to Barbados and back. Throughout this tale, women’s voices, often faint, can also be heard: Elizabeth, Coco, Elizabeth II, Julia, Ruby, Nanny, Dorothy Lindo, Frances Ann, Elizabeth III, Margaret, Ellen, Martha, Alice Lucy, and finally, Pamela.

I am aware that my title is a description no longer acceptable but please do not take offence. For modern eyes this is the least difficult contemporary description used for many of Charles Walter’s Barbadian forebears. Originally, a “coloured” human being would have had a white father and a black mother of African birth or descent. Over time the combinations became more mixed and formed into different social classes. The term “free” is obvious at a time when all the black, and many of the “coloured”, population were not. Now read on.

**************************************

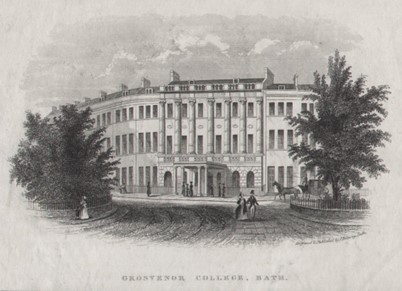

Had they but known it in 1861, both Charles Walter Cumberbatch and his bride-to-be, Pamela Pillinger, were living relatively near each other in Somerset. Pamela was a ten-year-old schoolgirl at Queen Charlton, Charles aged 15, was at 12 Hanover Street, Bath with his widowed mother Elizabeth, 36, his aunt, Miss Margaret Barry, (his mother’s sister), aged 17, and his younger brother Alphonso Elkin, aged 12. Everybody in the household had been born in Barbados. Though Bath was past its Georgian heyday, plenty of visitors still came, just as they had when Roman Legionaries shook off their sandals, unshackled their armour and rested their weary bones in the medicinal waters. In the 1860s much of the current crop of arrivals were aged infirm, or came hoping for respite care, as can be guessed at by a demand for “wheel-chair-men”, available for hire, a trade followed by yet another Pillinger, (unrelated to me or Pamela except by name.) Elizabeth Cumberbatch’s family were neither old nor decrepit, but they would have been seen as border-line exotic.

There is no sign of them in England before 1861, and by 7th April the day the Census man called, they had been in Bath a few months at least. At the Grosvenor College Prize Day, just before Christmas 1860, “C. Cumberbatch”, recited a poem, “The Chameleon by Merrick”. In February came an award of the “Godfrey Scholarship” which allowed Charles Walter to “receive [his] education gratuitously, with other privileges.” By June, both he and Alphonso were noted at the bi-annual prize-giving. Charles figured prominently with prizes for French, History, Maths, and tellingly, Drawing.

“Mrs. Cumberbatch” who had become a Benefactor, donated prizes for “Aggregate of Mathematics”.[2] When her two sons came first and second in this category you can almost hear the groans from here.

For those researching their family tree, it is obligatory to go, step by step, from the known to the unknown. For those trying to write a story, numerous flashes, both forward and back, are confusing, not to say tedious for reader and writer alike. Therefore, I shall present the tale chronologically.

Charles Walter’s story begins with his background, the birth in 1726 in Barbados of Abraham Carleton, who afterwards changed his surname to Cumberbatch, a condition under the will of his grandfather. He was both rich, and a member of the Barbados Assembly, styled “The Hon.” He was an elder statesman of 30 years political service by mid-1785 when he came to Bristol for the benefit of his health. Unfortunately, he was already terminally ill. He died on 25th July 1785 aged 58 and was buried in Bristol Cathedral where a tablet records that he bore his illness with “uncommon patience and fortitude”. [3]

Abraham Carleton Cumberbatch, father of Lawrence Trent. A family resemblance? A certain superstar, a descendant of Lawrence Trent’s elder brother, would be well cast as his own ancestor.

Abraham’s second son, Lawrence Trent Cumberbatch was born about 1762. He owned large plantations in Barbados, with buildings and stock moveable and immoveable. His “property” included enslaved people, men, women, and children, working indoors and out, domestic, in the cane fields or engaged in all manner of skilled and unskilled labour. A lifelong bachelor, Lawrence had no legitimate issue, but he had at least two “outside” children, two sons, not officially recognised, but who seem to have been an open secret. The elder boy, John Edward Cumberbatch, was born about 1800, though not baptised until 25th January 1807 in a ceremony shared with his mother, “Elizabeth”. Like many of the enslaved people she had no surname. Elizabeth is believed to have been about 15 or 16 when John Edward was born. If this is the case then Lawrence Trent was more than 3 decades her senior, but even if the age gap was three years rather than thirty, it must not be overlooked that this young girl, hardly more than a child, would have no say whatsoever in the matter. We can pretty it up by calling it a meeting, or even a “transaction”, though rape is still rape whatever you like to call it. All that can be said for this “droit de seigneur” is that any child resulting from such a union might at least stand the chance of growing up to be “a free coloured”. The description would not apply to those fathered, not by the master, but by one of his (white) employees. They would presumably go back into the melting pot, as “coloured” (or worse, mulatto) without the “free”. So are distinctions of class born. I need hardly add that such relationships were male upon female, and not the other way round. A second son, Richard, was born in 1812 when Lawrence would have been about fifty. His mother was also named Elizabeth. She may or may not be the same Elizabeth but given there are a dozen years between the boys’ births, I am dubious, though the two are linked together as brothers.

Lawrence Trent died aged 71 on 18th December 1833. His complicated will, with several codicils, leaves the far greater part of his fortune to his legitimate relatives, nephews and grand nephews, but my interest lies with the lesser bequests:

£100 to “my friend and overseer” Thomas Smith Harding.

Slaves to be manumitted: Charles Ramsay, Isaac Aboab, (his name indicating he was an Ashanti, then the Gold Coast, now modern Ghana, one of the few African names salvaged), Billy Trent and Hope, (males), Coco Sandiford, (a female), plus £10 each in Barbadian currency.

The Lavine family: Mary Lawrentia, Francis, Abraham, George Beckwith, and Lizzie Lavine, “free coloured persons, the house in Speights town where they live, with the land on which it stood, and £100 each.”

John Edward Cumberbatch and Richard Cumberbatch, “free coloured persons, the house where they reside in Speights town, with the land on which it stands, and £100 each.”

A codicil gives J.E. & Richard, and the various Lavines, an extra £100 each. Though no relationship is stated, both households stand out for similar and unusual favour and it seems likely that all were “below the blanket” family members.

Without additional money, the will frees other people “from service and servitude”, Mary, or May, Hinds, “a young coloured woman”, David, “a coloured boy”, Sarah, Mary & Margaret, “coloured girls” and “Thomas Hendy, plus the offspring of Thomas Hendy, manumitted for his skillful service and attachment to me.”

In a final amendment, the legacy to Coco, the “house and maidservant” who remained with her Master despite being officially liberated, is upgraded to £50. In addition, he left her a gift of three slaves of her own, Sukey, an adult woman, and two boys, Marcus and John Thomas Marcus, with another £10 per annum for rent for the term of two years “for her extraordinary care and attention to me in my long and painful illness.”

There is nothing good that can be said for the ownership of one person by another, but it seems to me that Lawrence Trent’s will and the details of Coco’s life suggests that in some cases close relationships developed between Master and certain slaves, whether they were linked by blood or not. Without viewing other, particularly earlier, wills, I cannot say whether this was usual.

Those liberated under the terms of the will would soon be joined by all the slaves on the island of Barbados. On 1st August 1834, 750,000 enslaved people in the British West Indies were declared “free”. But not quite. There was a fudge. To aid the transition period an “apprenticeship” scheme was initiated in which the people had to continue working for their former masters. This, understandably, was not wildly popular. After another four years, on 1st August 1838, full emancipation was established, officially enabling everyone to pick who they wished to work for. [4]

The newly freed were not compensated for the loss of their liberty. The Owners received financial awards for the loss of their human property; some of which is still being claimed to this day. The estate of Lawrence Trent Cumberbatch was compensated for 177 slaves, and it is especially chilling to see the details and the value placed on each.

- 5 Head People £500

- 4 Tradespeople £400

- 3 Inferior Tradesmen £225

- 75 Field Labourers, (33 male, 42 female) £5,625

- 33 Inferior Field Labourers, (16 m, 17 f) £1,320

- 4 Head Domestic Servants (1 m, 3 f) £400

- 5 Inferior Domestics, (1 m, 4 f) £250

- Children under six, (14 m 17 f) £310

- Total £9,035. (Approximately £1,502,459 today)

Three girls, Sukey, Bella Ann and Rebecca, and a boy, Samuel Edward who were born after 1st August 1834 were not part of the tally, nor were two males, Robert and Sam Hackett, who had died since the last registration. Those manumitted by the will, including the three left to Coco were named but discounted.

Coco was born about 1800, one of a group of 25 enslaved people, seven of whom were under eight and aged ten was recorded working as a full time as a “grass picker” weeding in the fields. When her owner Ann Sandiford died in 1828, she was passed to Ann’s brother, Lawrence Trent Cumberbatch. Coco was one of a few of these he retained as domestic servants. Of her human legacy, Sukey, may have been her own sister and the boys about two years old. It is speculated that Marcus, recorded as “coloured”, may have been the child of an association between Coco and Cumberbatch. The infants were born only three months apart so cannot both have been Coco’s children. In 1835, Coco married a butcher, John Graham, in Speights town and they went on to have a daughter and son, Mary Eliza and Robert. In the award scheme after emancipation Coco was compensated £46. 12s 1d. for the loss of her three slaves, one domestic and two children.[5]

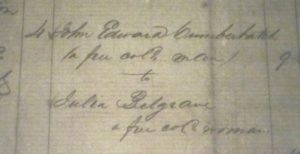

John Edward Cumberbatch, Lawrence Trent’s son, who was born c1800, married Julia Belgrave on 4th June 1833.

John Edward Cumberbatch, Lawrence Trent’s son, who was born c1800, married Julia Belgrave on 4th June 1833.

Both were “free coloured” persons. They probably lived in the house which John Edward inherited (with his brother) at Speights town, a historic port which was also known as “Little Bristol” (!) with his wife and family.

Julia, who was born on 20th July, 1804, was baptised almost a year to the day later at St Peter’s church, the daughter of John Thomas Belgrave and his wife Elizabeth, nee Phillips, with both parents described as “free mulattoes”. The Belgraves were one of the most prominent (and wealthy) “coloured families” of Barbados. Julia’s grandfather, Jacob Belgrave I, the owner of a plantation called The Adventure, and a slave owner, was a political activist on behalf of the rights of those of mixed race. In 1799 he and his sons, John Thomas and Jacob II signed the Memorial Declaration which challenged discrimination against non-whites and called for “the protection of coloureds under the law”. Jacob I died in 1803 and his son John Thomas, born 1769, inherited the property which he extended to 144 acres with 99 slaves.

Belgrave family life was very complicated with multiple marriages and liaisons which resulted in many offspring. John Thomas died in 1810, by his will appointing two executors, his wife Elizabeth and brother Jacob II. Elizabeth was excluded when she married Renn Phillips Collymore, a member of another prominent non-white family which left Jacob II in sole charge of the financial affairs of his brother’s estate.

Any talk of insurrection placed the “coloured” families of varying social class, (some of whom, as previously noted, had their own slaves) in a quandary. Whether to support the Status Quo and the white planters, or the rebels, whose possible victory might result in giving them, the “coloureds”, more political “clout” perhaps even voting rights. People generally act in what they feel is their own best interests.

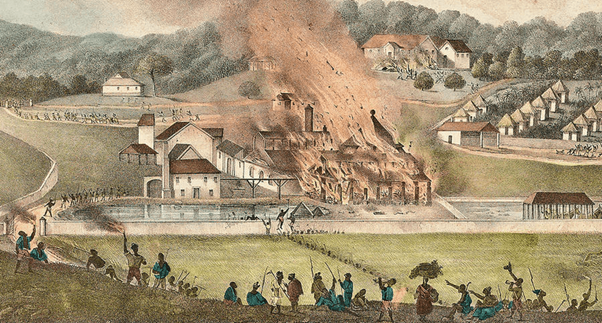

In Speights Town, in April 1816 John Edward Cumberbatch, aged 16, and his future wife Julia Belgrave, who more than likely knew each other, would have been aware, and were probably terrified by the news coming in from the estates, the danger afoot, the excitement of the call to arms of the Militia, even the awful horror of being burnt alive in a conflagration. A major uprising of the slaves in Barbados, known as ‘Bussa’s Rebellion’ after one of the leaders had begun.

A poster produced by the rebels. (Copyright National Archives)

In 1807, after a lengthy struggle, the House of Commons in London had voted to end the British Slave Trade. This did not end Slavery itself but outlawed the buying of the recently enslaved in Africa from the traders, the grisly business of packing the human cargo into ships and taking those who survived across the sea to market in the West Indies. The Royal Navy blockaded the West African ports, boarded as many suspect ships as they could catch and liberated the cargo.

To those already enslaved in Barbados and the rest of the West Indies, this made little difference to daily lives, but offered a glimmer of hope that they too might soon be free. Over the years, rumours kept the dream alive, with some believing that they had already been freed but that the plantation owners had kept the information from them. Hopes rose in Barbados when, in 1815, Governor Leith arrived back in the country supposedly carrying with him a “Free” paper. This proved to be false news. The document was simply a piece of legislation to register all the enslaved persons on the island, men, women and children. In the ensuing outrage and disappointment, months of secret plotting spilled over into rebellion.

Acknowledgement: https://donnaevery.com/blog/2016/07/28/bussa-rebellion-vaucluse/

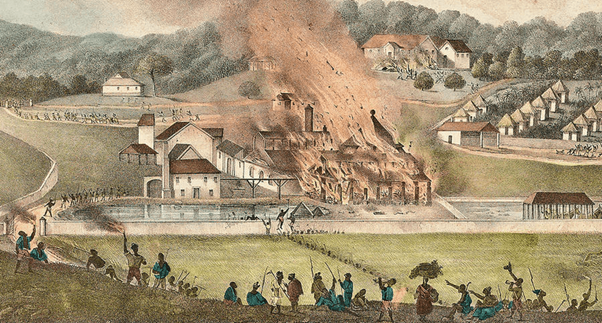

On 14th April 1816 the enslaved rebels gathered, threw down their scythes and set the canefields on fire.

The Rising was ruthlessly put down in only two days. Bussa’s four hundred fighters were no match for the superior firepower of the Militia and regular troops. About fifty rebels including Bussa and other leaders were killed, “during their mad career”, with an estimated seventy more summarily executed “in the field”. Three hundred were taken prisoner, of whom 144 were also hanged. More than a hundred others were exiled to other islands. Only one white civilian and a black (professional) soldier died during the fighting, but the financial damage was severe. One of the four parishes affected was St Philips. Details of the owners and their costs reached London in June 1816:

The Account of the loss in St Philips Parish with the owners’ names and estates.

Mr Scott. Bailey’s. [Bayley’s] Dwelling house, furniture and clothes completely destroyed. Many canefields burnt. A number of negroes killed and executed.

Mr Scott. Wiltshire. Buildings and canefields burnt.

Mr. Grasset, Golden Grove. Furniture, plate and canefields burnt.

Lord Harewood. Thickets. Furniture, some canefields destroyed. Many negroes killed and executed. 20-odd now absent.[6]

Mr T. Barrow, Sunbury. House much injured, furniture destroyed and several canefields. Some slaves killed and hanged.

Mr Crookindall, River. Furniture, canefields burnt. Many negroes killed and executed.

Mrs BELGRAVE, Branford, Curing House with many hogsheads of sugar and many cornfields burnt, some slaves killed and executed. At this estate several hundred insurgents assembled and made a stand against the St Michael Militia.

Judge Gittens. Interior of House destroyed, canefields burnt. Rum and sugar lost. Several negroes killed and executed.

JACOB BELGRAVE, and RUBY, free mulatto. House and every other building destroyed and canefields burnt. Several negroes killed. The fire commenced at this property.

Mr. Braithwaite, Fowl Bay. House, furniture & canefields burnt. Estimated loss £15,000.

M. Weeks, deceased. Mangrove. Buildings, canefields, destroyed. A number of slaves killed and executed.

Bayne & Clark, Marlemoul. House & offices wrecked, plus records, receipts, books destroyed. Large cargo just imported burnt. Est. loss, £15,000.

J. Simmonds, Harrow. 104 acres and 67 acres at Four Square, burnt.

Mr. Franklin, Contented Retreat. Building destroyed plus 20 tierces of sugar and rum destroyed. Several Negroes executed one or two killed.

Lord Harewood, Mount. Every building destroyed, canefields burnt, rum and sugar thrown about the yard. A great many slaves, many leaders in the plot, killed and executed.

Mr. J. Bovill, Greens. Nearly all crop burnt, a few negroes killed or executed.

Mr. J. Podmore, Edeys. Many acres of cane burnt, a few negroes killed or executed.

Mr. T. Yard. Cottage and 20 acres of cane burnt, 3 negroes killed and executed.”

“Many more in the other parishes have suffered materially. The Negro Houses on the estates where negroes revolted through which the Militia passed were set on fire by their commanding officers from motives of policy. Many more taken have been set on board a vessel in the bay to await the result of their trials.

“Many have been condemned in the parishes where they revolted upon full evidence of their guilt before a Court Martial. A court of enquiry is sitting, before which several convicted [have had] their sentences carried out in the plantations to which the offenders belonged.” [7]

The Governor gave a long “Address to the Slave Population Barbados” re-iterating that slavery had a long history, going back through time immemorial; that slavery was rife in Africa and that it was their fellow Africans who first sold them to the slave traders who had brought them across the ocean. If slavery was abolished, he asked, what would then happen to the old, the sick and the children with no-one to look after them?” Blah. Blah.

Imagined portrait of Bussa on a postage stamp.

Imagined portrait of Bussa on a postage stamp.

There is little known about the leaders of the rebellion apart from a few names. They included free men as well as Creoles and both women and men. The man for whom the uprising is named was Bussa, an African born Igbo, a senior ranger on Bayley’s Plantation, a position which would have given him more freedom than usual to move about. A prominent woman in the insurrection was Nanny Grigg, a domestic worker at the Simmons’ Plantation. She had taught herself to read and write and was highly valued at £130. A statue of Bussa has been erected in Bridgetown; currently there is a call for a similar statue dedicated to Nanny as an inspiration to women.

Now consider the immediate revenge taken against the Bussa insurgents, executed, hanged (lynched) on the spot, then the horror of the callous firing of the “Negro Houses” as a matter of “policy”, rendering all inhabitants, whether involved or not, burnt to death, or at best homeless and destitute. How many innocent children died?

In the aftermath of the rebellion those still alive, the beaten, bereft and still enslaved, returned to their work. Which seems to be the basic result of all rebellions that start bottom up. Martial Law stayed in place for months.

Now cast your eyes over those who lost property and note two people with a familiar surname, Belgrave. Mrs. Belgrave, whichever one she was, who kept “the Curing House”,[8] and Jacob Belgrave, who was at his holding, with “Ruby”, probably his latest flame. At Mrs. Belgrave’s a mob of insurgents had been vanquished by the Army, and Jacob’s property was “where the fire commenced.” This might suggest that both Belgraves (well-heeled coloureds) were so unpopular (perhaps even hated by the rebels) that both locations were specially chosen. Jacob Belgrave was none other than Jacob II, the brother of John Thomas, and Julia’s uncle.

Jacob II was a well-known character, something of a hustler, who often had something “going cheap”. Like “100 tierces[9] of new pilchards, contents 1,500 in each. Sell cheap for cash.” “Single double or single Gloucester Cheese, superior quality. Cash”. Perhaps “a light curricle, single horse or pair. Cheap.” Or better still, “a ‘Blood’ Horse, ‘Scipio’, Pedigree short but correct, dam a thoroughbred, sired by ‘Obscurity’ who was sired by the famous ‘Eclipse’. Warranted sound.”

In 1815 Jacob II was named in the Barbados Mercury, 26th September, by S.F. Collymore (another member of one of the elite coloured families) disputing the ownership of a woman slave, a “Runaway”, called Jenny, who had very black skin, was a slender, 5 ft 4 or 5 inches tall with a slight speech impediment, and the fingers of one hand “drawn”. Her husband, Tom Pigeon, was “a short yellow man”, formerly belonging to Widow Barrow but presently the property of Mr. Jacob Belgrave who was supposed to have her concealed by some of his connections. 10 guineas reward was offered for return of the slave, plus another 5 guineas for one giving evidence which would lead to the same result.

In 1825, Jacob II signalled his intention of leaving the island, and took with him one of his daughters, a comely fifteen-year-old, called Dorothy Lindo Belgrave, baptised at St Michael’s, 17th October 1810, daughter of Jacob and Charlotte.

As will be recalled, Jacob II was the sole executor and trustee of the will of his late brother, John Thomas, who had left his property to his son, a minor, John Thomas II. The lad, who had been sent to England aged six to be educated, had recently reached his majority of twenty-one years. Having apparently been content to leave the management of his affairs in his uncle’s hands until then, he was surprised to be confronted suddenly in London by Jacob II, who he had not seen in the intervening years. Jacob II said that he had £2,000 to settle with him there and then, but further outstanding matters concerning the estate could be quickly concluded (and very easily) if the young man would consider proposing marriage to his daughter, Dorothy Lindo. A marriage contract could then be drawn up settling the whole estate upon her. (As the law stood at this time, a wife’s property automatically became her husband’s.) It sounded tempting. John Thomas would then have the £2,000, the estate and all accoutrements belonging, estimated about £30,000, (approx. £3,586,987 today) plus a very agreeable wife. J.T. at first hesitated saying he didn’t know the lady but after meeting her a few times, “her manners and conversation were such that he could not resist them”, he agreed to marry her, (nobody seems to have asked Dorothy whether she wanted to marry John Thomas!) and the settlement was executed. After this he discovered that Jacob II had 13 children (some reports stated 13 daughters) and thus Dorothy would only be entitled to 1/13th part of the estate. J.T. found himself without the £2,000, or the lady and all he would receive was 1/13th part of the fortune. At this point J.T. initiated legal proceedings against his uncle. Rather than £2,000, the defendant, Jacob Belgrave, had offered £879, though there were two other sums of £1,000 and £262 outstanding as part of the writ. Whilst the lawyers deliberated, the defendant “put the document [the marriage contract] in his pocket, and he and his daughter departed and went aboard a ship called the Tropic, intending return to the West Indies”, where, allegedly, they would “replay the same farce” to make a better deal elsewhere. The court advised John Thomas to accept the £879 obtained so far and pursue the other sums at a later date. Reports that Jacob had been apprehended were denied by John Thomas who wrote an aggrieved letter to the Morning Post on 14th March from his address in Surrey Street, Strand:

“Jacob Belgrave left his lodgings abruptly early in the morning the warrant was served. A search has been made for him aboard the Tropic but he has escaped, I believe with the whole of my property, the lease and settlement in his pocket.”

(I do not know the outcome of this sorry business and, having wandered far off the point of the Cumberbatch story and I will leave further accounts to academics. My precis is from very long-winded newspaper accounts in the vernacular of the day which snidely convey the skin tone of the protagonists. Dorothy, the “beautiful and amiable daughter” is also a “West Indian Charmer”. The temporarily deluded Plaintiff also “has a little of the West Indian complexion about him.” Finally, a postscript. “The details of the case caused much merriment in Court.”[10] In Barbados, among the “coloureds”, it was mostly about ‘class’. In England it was both ‘race’ and ‘class’. The article leaves no doubt that to the English of the day, people of colour, of whatever their hue or social class, were figures of fun.)

It is probable that everybody in the “rich coloured” community of Barbados would have been aware of the manner in which Jacob II tried to dupe Julia’s elder brother. She was probably angry and embarrassed in equal proportions. As to John Thomas Belgrave II, he returned to Barbados from London in 1826 presumably to sort out the mess. He must have lived a quiet life thereafter, for nothing else is known about him.

I have speculated that John Edward Cumberbatch and Julia Belgrave knew each other as children. I believe their families, especially those at the top of the pecking order flocked together. They certainly intermarried, as with the Collymore-Belgrave match above and another example, a notice in The Barbadian of 24th July 1833 when John Edward Cumberbatch of St Peter’s parish “hath petitioned the Governor for letters of administration to the estate of Elizabeth Collymore, formerly of this island, but late of the colony of Trinidad with her will annexed.” This seems to be the only time J.E.C.’s name was noticed by the papers.

John Edward died aged only 38 from an unknown cause, and was buried at St Peter’s, Bridgetown on 16th August 1838. When his will was proved on 24th October, he left everything to his “beloved wife Julia” and after her death in equal shares to their four young children, provided she did not remarry, in which case the property should go straight to the children. She could sell the house and use the money to buy another to live in, provided the children were not disadvantaged in any way. John Edward made his mark and named the executors as Francis Cumberbatch, (unknown) Richard Cumberbatch, probably his brother, and Julia.

The scheme to compensate owners for their losses indicates that both he and his wife had their own slaves: John Edward received two awards: £75. 14s 6d (six enslaved) and £116.10s 4d (eight enslaved and Julia £19. 19s 3d (two enslaved) and £3.17s 6d (one enslaved).

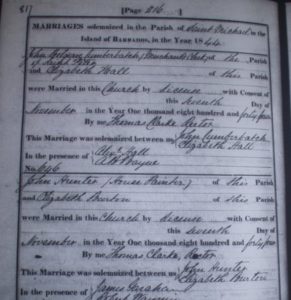

The eldest of the children, John Belgrave and Eliza, were about twelve years old when their father died. I have no information about the family until John Belgrave Cumberbatch married Elizabeth Hall, by licence at St Michael’s on 7th November 1844, with witnesses Alexr. [sic] Hall, and A.B. Bayne.

According to the original parish register all parties signed, but every entry on the page appears to have been copied in the same hand. The groom’s occupation is given as “merchant’s clerk.” It is worth noting that the church at this time, (in common with British Parish Registers) had given up any mention of complexion.

According to the original parish register all parties signed, but every entry on the page appears to have been copied in the same hand. The groom’s occupation is given as “merchant’s clerk.” It is worth noting that the church at this time, (in common with British Parish Registers) had given up any mention of complexion.

Elizabeth Hall was baptised at St Michael’s Barbados on 2nd September 1823, the daughter of Frances Ann Hall with no father named. It would certainly seem that Alexander Hall, one of the marriage witnesses, is likely to be a relative. It is a rather distinguished first name, and in the Barbados records I found only three with the surname Hall.

Alexander Hall, born c1794, could be Elizabeth’s and Alexander’s putative father, but not the marriage witness. He died aged 42 in 1836.

Alexander Hall married Nanny Mary at St Philips, Barbados on 28th January 1841. Along with his bride, he marked with an ”x”, so I think we can probably discount him given that the witness at Elizabeth Hall’s wedding was registered as able to sign his name.

The third Alexander Hall was a British Merchant Seaman, whose M.N. record in British archives is specific. He was a “Black Man” born in Barbados on 16th October 1822. He went to sea as a boy, and by the time his details were recorded, 20th June 1847, he was the mate aboard an un-named ship and when not at sea, resided in Newport, Wales. To become a mate, one step down from Master of the ship he would have to be literate to pass the examinations. Indeed, the record shows he could write. At 25, he had been awarded his Mate’s ticket. My small band of readers will know of my soft spot for seamen, especially those who sailed in and out of our Bristol Channel Ports. I want him to be Elizabeth Hall Cumberbatch’s brother, but I cannot prove it. Regrettably I have no more information about Alexander. Little is known about Elizabeth’s family which had the usual complications and mysteries. By 1861 when she had arrived in England with her two sons, she was accompanied by her much younger sister, Margaret Barry, who may (or may not) be the daughter of a different father, a planter called James Barry.

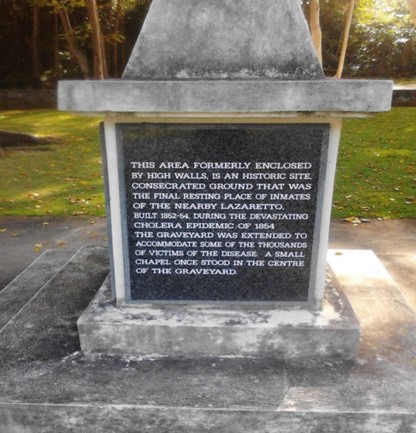

Elizabeth and John Belgrave Cumberbatch had four children of whom the only survivors were Charles Walter and Alphonso Elkin. A baby girl, Hileria died, aged one, in 1850. The other child, William Darnley, was four years old when he died along with his father, John Belgrave, aged 28, probably among the first of the fatalities of the cholera epidemic which ravaged Barbados in 1854. More than 20,000 Barbadians died, with 9,127 confirmed deaths in St Michael and Bridgetown alone.

A memorial stone to some of the cholera victims of 1854.

As can happen, a disaster draws attention to the need for change. Many Barbadians lived under wretched social conditions with poor public health infrastructure. The changes introduced by the Barbados government were fairly minor but vital, regular cleaning and washing of the streets and in 1861, piped water. The widowed Elizabeth Cumberbatch was ahead of the game. In 1858, (The Barbadian, 27th February) names her as having six shares in the Water Company. Also among the shareholders are the familiar surnames of Belgrave and Collymore. Elizabeth also apparently owned the family house in Swan Street, Bridgetown and perhaps other property which she was able to lease or let to others. She was moderately well off when she decided to travel to England.

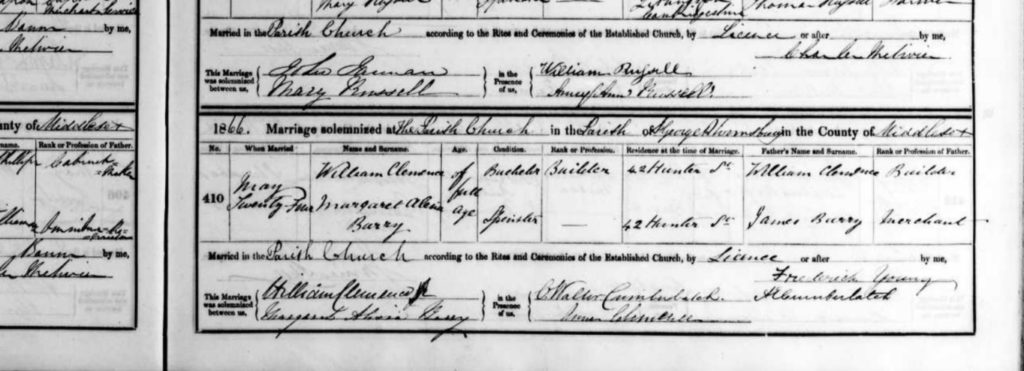

In 1871 Elizabeth was absent when the latest census was taken. It is most likely she had returned to Barbados to deal with pressing business affairs. Her family, now settled in England, were scattered about the country. On 24th May 1866, her sister Margaret Alesia Barry was married by licence to a builder, William Clemence at St George, Bloomsbury. Both parties were of 42 Hunter Street. Aunt Margaret had obviously remained close to her two nephews: they witnessed her marriage, from which we have good signatures of both. Plus, there is the revelation that C.W. evidently preferred to be called Walter!

Elizabeth Cumberbatch was not in evidence at her sister’s wedding, but of course, she could well have been in the congregation. There is nothing to say if she attended that of Charles Walter & Pamela Pillinger in 1877 in Bristol either.

By 1881, Elizabeth was back in London, living at 40 Lilyville Road, Chelsea where a spinster, Ellen Locke, aged 29, born in Taunton, who lived on “dividends” headed the household. Elizabeth, by then aged 56, “born in the West Indies”, whose own income derived from “property abroad” was apparently the lodger. They had a young servant, Louisa Green, aged 19.

Elsewhere in 1881, Margaret Clemence “married, aged 36, born in West Indies” was at St Pancras, a visitor to the menage of James Wray, an Independent Church Minister. Her husband William, 38, who was born at St Martin-in-the-Fields in Middlesex, was at Barton-upon-Irwell, Lancashire, an unemployed builder’s clerk, described as “brother-in-law” to Annie Stocker, also a Londoner, with whom he was lodging. Among Annie’s children was a baby, Francis Stocker, aged one. In 1891, Margaret and Willliam were re-united under one roof at Barton, apparently in improved circumstances, both for the marriage and their prospects. William, now 48, had a job, as an “oil market manager” though they lived in “rooms” in a shared house. Written in the column just above William’s age, in a different hand, is a rare addition, “coloured”. (This must refer to Margaret. There is nothing anywhere else to indicate that William may also have had black roots.)

In 1901, Margaret, once more without her husband, was living at Beccles, described as “aunt” to Francis A. Stocker, an articled clerk, the same one-year-old infant of 1881. William, also at Beccles, was a retired oil agent, of 58, married, a boarder with a Mrs. Godwin. Nothing more is known of either party. Whether or not Margaret was in touch with her sister, or her nephews in her later years, is not known.

Ten years before, in 1891, now at 33 Sinclair Gardens, West Kensington, the situations of the two women, Elizabeth Cumberbatch and Ellen Locke were directly reversed. Elizabeth, aged 66, headed the house, “living on own means” whereas Ellen, 39, was a “servant”. In an all-female household, the other occupants were Catherine Janaway, a “companion”, 35, and a servant, Catherine, Sambrook, aged twenty.

Sinclair Gardens was Elizabeth Cumberbatch’s final address. She died there on 12th September 1897. Charles Walter, her son, was the informant “present at the death” though she made her younger son Elkin, by then an extremely successful eye surgeon, an executor of her will. On 30th December 1880, Elkin married a rich heiress, Alice Lucy Moffatt at St Michael’s Belgravia. In 1911, he and his wife were living at Portland Place, with no fewer than seven servants, including two footmen. When Alice died in 1922, she left assets amounting to £351,730, a very considerable fortune.

It was a long way from Pamela’s origins in a gardener’s cottage in Queen Charlton, and I would love to know if the two sisters-in-law, Pamela & Alice ever met……

When Elkin himself died in 1929, he left £1,000 (approx. £18,128 today) to his housemaid Millicent Jane Rayment, “who has served me faithfully for more than 40 years”. Which is [almost] where we came in.

Elizabeth Cumberbatch left £14,163. 15s 7d. (£2,361,364 today)£In her will, she calls Ellen Locke her “esteemed friend” who is to have £25 for mourning clothes and all wearing apparel. I can’t help feeling that Ellen was not entirely delighted with her legacy. I have memories of old clothes, even lacy Victoriana, which had obviously been cast off by better-off persons, given to my brother and I for “dressing up” games. They smelt of sweat, stale scent and moth balls and soon disintegrated.

Footnotes

[1] From ‘The Drinker’s Dictionary’, in the Pennsylvania Gazette, 1737. Barbados is the birthplace of rum. It has been produced there for over 300 years.

[2] Bath Journal, 20.12.1860, 7.2.1861 & 13.6.1861

[3] I recommend here that you look at the excellent blog: https://cryssabazos.com/2018/08/29/a-17th-century-sugar-plantation-in-the-caribbean/

[4] By contrast, slavery in the USA was not abolished until 3rd January 1865.

[5] Legacies of British Slavery

[6] Edward Lascelles, 1st Earl of Harewood. Many slaves received the surname of their owners. The actor David Harewood is a descendant of one of Harewood’s slaves. His portrait now hangs among the Harewood ancestors at Harewood House. BBC 6 o’clock News 5.9.23.

[7] 6 June 1816, Public Ledger & Derby Advertiser.

[8] The Curing House, the end of the process of sugar production. After the cane was cut by hand, a foot off the ground, it would be stacked vertically, then quickly taken to the Crushing Mill before it could dry out. The brown cane juice was extracted and boiled in copper pans, then “cured” in clay pots at the Curing House. Coarse brown sugar takes a month to “cure”, and white sugar a few months longer. The price is being paid two millennia later by those of us with false teeth. Retribution of a kind.

[9] An old measure of quantity between a barrel and a hogshead. Bravo!

[10] London Telegraph, 7.3.1825, Colonial & Commercial Weekly Advertiser, 6.3.1825

Leave a Comment