Chapter 11 of my book, ‘Killed in a Coalpit’, about the lives of the Kingswood district colliers is entitled ‘A Young Hero – Edward Albert Powell’, who was known as Ted. At the age of 14, in 1907, he managed to stop ‘a journey’ of loaded coal trams at Parkfield Pit, rescuing an older miner, George Sloper, from certain death. The management were so impressed with the boy’s heroism that they awarded him a testimonial which was proudly shown to me by Ted’s granddaughter Lynette Bartlett Sutton and her mother Beryl many years ago. At the time I was preparing a supplement to my first edition of ‘Killed in a Coalpit’ and used a copy of Ted’s certificate as the cover. Some forty years later (!) my amateur photocopied version of KIACP had been taken up by the South Gloucestershire Mines Research Group, a ‘proper’ book was envisaged and was in preparation for publication. Due to marvellous serendipity I was contacted ‘out of the blue’ by Lynette, who I had not heard from during the intervening years, and who was unaware that a new edition of the book was imminent. Lynette told me, almost apologetically that she had some coalmining photographs and wondered if I could advise her what she should do with them! A few weeks later and the book would have gone to print. It still gives me goose pimples. In a state of euphoria Steve Grudgings of the Group and I viewed the pictures. We managed to stop the press in order to include the treasure trove and an extra chapter about Ted was added, which forms a fitting memorial to all those who risked their own lives in the local pits when trying to save others.

Lynette and I have kept in touch irregularly since. She has traced a great number of her ancestral lines from the greater Bristol area, including the Dando family, several of whom, especially Isachar, make notable appearances in the book. Some of the other direct and indirect ancestors are slightly less than heroic. Two are the principal subjects of this article, the husbands of sisters, Sarah Ann, born 1862, and Emily, born 1875, the daughters of a collier, Simon Williams and his wife Harriet Davis.

In 1871, Sarah Ann Williams, aged eight, was living with her father and mother at Soundwell, a colliery district in Kingswood, east of Bristol. She was proudly shown as ‘a scholar’ in the census that year, a status confirmed when she signed the register at her wedding to Thomas Clements, a coalminer, at St James’ Church, Mangotsfield in 1882. Her bridegroom, who marked with a cross, stated he was 18, though he was born, like his new wife, in 1862.

In 1891 they were living at Gordon Road, Whitehall, with their children Lily aged four, born in Stapleton, Thomas, 3, and Rosina aged one, both born in St George. I believe that before Lily there may have been another infant, even infants, who did not survive. At this time they eked out a probably meagre existence by taking a lodger, a gardener’s labourer called Sarah Harris.

In 1899, at the parish church in Downend, Emily Williams aged 23, married Alfred Hodgetts, a twenty four year old labourer. Like her sister, Emily signed the register with the groom again making his ‘mark’. To me this suggests that neither man was much of a catch for the girls, who had received some education, though Alfred as a Northerner, born in Lancaster, might have seemed slightly exotic, a newcomer to a tight community.

By April 1901 when the next census was taken the Clements family, now living at Hayward Road, Soundwell, had grown considerably, their names and ages shown respectively as Thomas Clements, 39, an underground collier, Sarah Ann, his wife, 38, and their children Thomas, 14, a shoemaker’s errand boy, Rose (otherwise Rosina) 11, Annie, 10, Henry, 7, Sarah Ann, 5, and Nora(h), 3. Another daughter, Charlotte, baptised 3 November 1895, at Downend Christchurch to Thomas and Sarah Ann seems have been inadvertently missed from the roster. The eldest daughter, Lily Clements aged 15 had already left home and was ‘in service’ at Lawrence Hill. A year later she would marry Abel Sutton, a railway plate layer.

Meanwhile, the Hodgetts, Alfred, 27 and Emily, 25, were living at Soundwell Road, with their infant, Joseph, aged 8 months. In 1902 Emily gave birth to her daughter, Dorothy May, just a few months before the death of her sister Sarah Ann Clements on 26 July 1902 at only forty years old. The Clements household in 1901 had suggested an averagely working class, but stable family. All this would now be thrown into turmoil.

His wife’s death drove Thomas Clements off the rails. Perhaps undone by grief he was unable to cope with bereavement as well as his brood of motherless children, but he made the most of things by going on a drinking spree. This was funded by a nest egg of £17. 15 shillings he had acquired from Sarah Ann, cash she had somehow managed to scrimp together or perhaps more likely it was a legacy from her father, Simon Williams who had also recently died. Though a tiny sum by today’s standards, to Clements it was a small fortune, equivalent to about £2,000.

In October 1902 he was taken to court by the SPCC (now the NSPCC), for neglecting his five children aged between 13 and five years old.[1] On the 12th October, at about 10 pm, four of the youngsters had run from their home to the Police Station saying their father had driven them out. PC Thomas said he had taken the children to their grandmother’s house, as was confirmed by Kate Williams, younger sister of Sarah Ann & Emily, the children’s aunt of 2 Portland Street, Soundwell, who told the court that they were in a bad way, very neglected. On his way back to the station, PC Thomas met the defendant staggering along the road with one of the children in his arms saying he didn’t know where the rest were. There was little food in the house. The children had been ill-treated. The next day Inspector Taylor, having had previous complaints about the father, and aware that the children had been begging for bread, went round to the house in Soundwell which had the ironic name ‘No Place like Home’. He found the father drunk, saying he had not seen the children since the previous night and didn’t know where they were. Clements said

“I had had a drop to drink. I have been looking for them.”

The father and the elder children occupied the front room, and though there was another bed, the eldest daughter had alleged the others were not allowed to use it and instead slept on sodden bags and old coats. Since his wife died and the father had come into the money, he had done little except spend it, though not on the children. Dr James Young of the SPCC who on 14th October also visited ‘No Place like Home’ found the two younger children, Charlotte and Norah, ‘in a very sad condition’. Though they had recently been washed and were wearing new clothes, otherwise it was apparent they had been caused unnecessary suffering.

Clements was found guilty and sentenced to 6 weeks imprisonment with hard labour.[2]

It is not known how the children managed before Thomas was released in mid-December, though presumably Rosina aged 13 took the reins. When he did return, there was another tragedy. In early February Sarah Ann, aged eleven, died in an accident, ‘falling from a window’. I have been unable to find a report of an inquest, but her burial took place on 8 September 1903 at Christchurch, Downend.

Even by the criterion ‘Drunk for a penny, dead drunk for tuppence’ (it is said that Thomas begged to pay for his daughter’s funeral) his funds must have been seriously depleted and by the following summer his situation had become critical. He enlisted the help of his brother-in-law Alfred Hodgetts, who had even more experience in matters of shady finance. Alf, described as ‘a perfect pest in the neighbourhood….[who]…..had been going about begging for years’, and had previous convictions, may even have suggested a plan to arouse sympathy which hopefully would net them some cash.

In September 1903, Tom (sic) Clements, 40, and Alfred Hodgetts, 29, brothers-in-law, both of Staple Hill, were charged with begging. PC Wood said he saw Clements going into shops at Eastville with a petition which read:

‘Friends. Help me to send two of my children to Dr Barnardo’s homes as I have to get together ten shillings for train fare. I shall be very grateful for any little help you can give me. Thomas Clements.’

There were several initials in the sheet and ‘A Friend’ figured, mainly for amounts of 3d and 6d. Hodgetts remained outside in the street, in Kingswood parlance, ‘Keeping Ki’ meaning keeping an eye on things.

On investigation, the constable added that he found that two of the children (Charlotte and Norah) had been taken to Dr Barnardo’s the previous Tuesday and that when the agent called, Clements had to be fetched from a public house. He had 8 shillings towards expenses and the balance was paid by ‘a Lady’.

This seems to have been the extent of the crime wave. The whole matter is so pathetic. Clements was sent to gaol for two months and Hodgetts for ten weeks.[3]

Charlotte Clements as a young girl in the Barnardo’s Home.

Charlotte and Norah were admitted to Dr Barnardo’s on 3 September 1903 and then transferred from Bristol to another institution, the Sheltering Home of Industry at Shirley, Hampshire, whence according to a scheme which had been running in Bristol since 1884, they would eventually be removed to Canada to ‘give them a better life’. The prevailing intelligence was that to complete the process of rehabilitation, it was kinder (!) to erase from the child’s mind all details of their previous lives. In effect the child would be ‘reborn’ when they entered the institution. Inquisitive children might be told their parents didn’t want them, or were dead.[4]

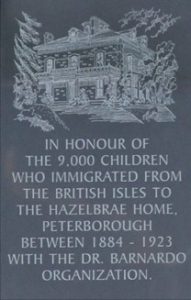

In accordance with this cruel policy, the sisters were separated in 1910. Charlotte sailed for Canada on ss. Tunisian on 13th March, and arrived at Quebec six days later. From there she would have been taken to the Barnardo Girls’ Home, called ‘Hazelbrae’, in Peterborough. Here she would have received board and lodging, been issued with uniform and would go to school. Following a short period ‘on trial’ she would live with the family to whom she had been assigned to learn housewifery. Wages were to be paid into a trust account administered by Barnardo’s. At the age of twenty one she would be free to leave, and to take her accrued wages with interest. In effect this household drudgery was paid slave labour. The system was unregulated to a great extent, and though some children would have been placed in kind homes, many suffered physical and sexual abuse.

A Party of Barnardo Girls ready for embarkation in Liverpool, 1909

Charlotte left in 1916, and did domestic work in Canada. She made a return visit to Bristol in 1931, when according to Lynette’s father, Henry Sutton, “played Hell with the Clements family”. She was keen to return to Canada as fast as possible with plans to go to America. On 4 March 1932 there was a setback. Charlotte Frieda Clements, a domestic, 34, was disbarred from entry into the USA. She told the officials she resided in Toronto and had $16 on her person. Her proposed destination was Mooresville, Indiana, to visit her sister Mrs Norah Dawes who resided at 141 East Main Street. She intended to stay for three months. She had previously visited USA between March 1920 and August 1930. Her nearest relation was her brother Thomas who lived at 16 Wellington Street, Bristol, England. She was 5 feet 4 inches in height, with a medium complexion and brown hair. She had immigrated to Canada in 1910 on an unknown ship.

On 25 August 1950, her last address in Canada given as 354 Goyeau, Windsor, Ontario, she entered America to join her husband Thomas William Mason of 8408 Centre, Detroit. Charlotte died in 1985 at Wyandotte. Michigan and is buried at Carmel Cemetery.

Norah, aged fourteen, followed her sister to Canada, embarking from Liverpool on the ss. Tunisian on 14 June 1912, arriving in Quebec on June 23rd. By the time she arrived it is possible Charlotte had already left for her placement though they remained in contact. After her marriage and the birth of two sons, Norah left Canada for the USA. She lived in Pennsylvania and then at Mooresville, Indiana. Her husband, originally from Plymouth, William Henry Dawes, a monumental mason, had an unusual claim to fame: he made the grave marker at Crown Hill Cemetery, Indianapolis, of the infamous John Dillinger, the bank robber, fatally shot by the FBI in 1934. Dillinger, lionised in the international press as a sort of Robin Hood figure, was nicknamed ‘Public Enemy Number One’.[5]

The marker is not Dawes’ original which has been replaced at least four times since 1934 due to souvenir hunters chipping off bits of the stone!

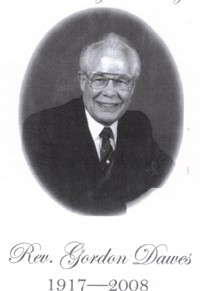

Norah and Henry’s elder son, Gordon, who was born in Canada in 1917, was ordained as a Minister of the Gospel in the Church of the Nazarene, which he served for 61 years, dedicated to the ministry and to missionary work around the world. He died in 2008 aged 91, at Castro Valley, California, mourned by Frances, his wife of 73 years, his son Gordon junior, 7 grandchildren, 21 great-grandchildren and 5 great great grandchildren.

His brother, Cyril, born in 1921, was tragically killed aged 16, along with another boy, when the van in which they were delivering laundry for cleaning was hit by a southbound Pennsylvania passenger train on a railway crossing. After the death of her husband William Dawes, Norah remarried and lived in Florida where she is buried.

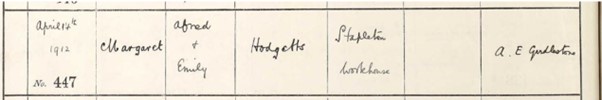

To return to the Hodgetts family: by 1891 Alfred was resident in Stapleton, a gardener, aged 18, with his parents and younger sister Lucy. As previously stated by 1901, a married man, he lived at the Staple Hill end of Soundwell Road, with his wife Emily (nee Williams, the sister of Sarah Ann Clements) and their baby son Joseph, born 28 July 1900. The couple’s later children were Dorothy, born 1902, Margaret, 1905, and Walter, 1908. The parents and younger children evaded the census in 1911, not through design, but possibly because they were homeless and wandering the streets. That the inevitable soon happened is shown by the christening of Margaret by then aged four on 14 April 1912 which took place at Stapleton Workhouse:

Meanwhile, the eldest son, young Joseph, born 28 July 1900, was listed in 1911 among ten schoolboy ‘inmates’ in one of the ‘Houses’ belonging to the Children’s Home at Charlton Road, Fishponds, looked after by a ‘house mother’, 32 year old Lydia Alway and a fourteen year old skivvy, Mabel Townsend. Rather than being in one grim Workhouse building, the ‘cottage’ system was designed to mimic a proper home life, though girls and boys lived in separate houses. According to family tradition, Joseph graduated to Kingswood Reformatory School, which originally started as a school for the sons of John Wesley’s itinerant ministers, long since moved to Bath, though still confusingly known as ‘Kingswood’. It had gone through various incarnations of which the latest was a penal establishment for boy offenders.[6] However, Joseph, apparently not incorrigible, was in Bristol Workhouse, by 10 September 1912, and left England for Halifax, Nova Scotia on 1 March 1913, aboard the ss. Hesperian one of the twelve Bristol boys in the contingent. His Canadian guardians were Robert and Jessie Donnelly. He married and had one son.

In 1911, his sister Dorothy, listed as ‘May Hodgetts’, aged eight, was also in the Charlton Road establishment, one of a dozen girls, in a House presided over by Alice Preece, 48, and included ‘a house girl’ of 14, Sarah Headford, promoted from the ranks as a servant.

Dorothy Hodgetts (photo shared on Ancestry UK)

Dorothy, as ‘May Dorothy’ Hodgetts sailed for Canada on the ss. Corsican, one of only two Bristol girls in the party. She arrived in Montreal on 9 June 1913 and resided at Aultsville, Ontario where her ‘guardian’ was the same Robert Donnelly, thus, happily it would seem that brother and sister were reunited. Dorothy began training as a nurse at Bethesda Hospital in 1922.

Dorothy had a daughter, Earlma Beth Stevenson in 1926, and another child in 1932, who was adopted. She had two husbands, John Staple who died in 1955 and Albert A.G. Hollister. Dorothy died in Toronto in September 1974.

By the time the Hodgetts children sailed, the scheme for sending pauper children to Canada from Bristol was drawing to a close; perhaps the ethics of the system was questioned; it ceased completely in 1915 because of the Great War and the advent of social workers, employed by the Council in the districts who would call on struggling families. For those selected for Canada, girls were apparently less in demand than boys, less troublesome, and work of domestic drudgery could always be found locally for them. For every year of operation a maximum of five girls were despatched by the Boards of Guardians of Bristol and Barton Regis, when for the same years the boys numbered in double figures. This was apart from the exceptional year of 1905, when there must have been a massive clear out of both sexes, for 40 boys and 32 girls travelled from Bristol.

Alfred Hodgetts died In Bristol Workhouse in 1937 though Emily’s death had not been traced. Their whereabouts may come to light in the 1921 census. Walter Hodgetts, their son, born 23 May 1908 went to Canada from Southampton in 1955, presumably on holiday, as he gave intention to return to England. He was at this time ‘a labourer, of 43 Grove Road, London W3.’

Of the remaining Clements children, Rosina was admitted to the Guardian Homes in Downend. This place is presumably the same as the Cottage Homes, one of the experimental schemes run under the same auspices as the Stapleton Houses where Joseph and Norah Hodgetts had lived in 1911.

The Downend Homes existed at least up to the end of the 1950s.[7]

In 1907 Rosina married James Edward Thomas, who was in the Royal Navy. In 1911 she was a bag mender, living with their son, also James Edward, at Whitehouse Street, Bedminster, and pregnant with their daughter Dorothy, born later that year. James, her husband, was serving aboard HMS Brooke when on 31 May 1917 he was killed at the Battle of Jutland. Their son, born shortly afterwards was given the impressive names Percy Jellicoe Beatty Thomas, thus commemorating his father through the surnames of the two Admirals at the battle. He died in 1967 aged 50.

By 1911, Thomas junior, born 1888 was a collier, living at Soundwell with his wife Mabel and two young sons, Harold and William. There is a probability that he went to work in Wales with his father, Thomas, who in 1905 married his second wife Sarah Vaughan in Pontypridd where they were living in 1911.

Annie Elizabeth, born 1892 and Eliza, born in 1894 died without trace. Henry, born in 1898, who suffered ill health, is thought to have joined his father Thomas and brother George in Wales. He married and had children, and died in 1937.

As to Lily Clements, the eldest sister, who managed to escape by way of her early marriage to Abel Sutton, she gave birth to Henry Sutton who married Beryl Powell, the daughter of Ted Powell. A man in his life has many different facets. Ted died aged only 57, having had a clandestine lover for fourteen years. As he lay dying, when only next of kin, or at least blood relatives were allowed, his eldest daughter, Dorothy Powell, sister of Beryl Sutton, managed to smuggle his lady friend to his hospital bedside to say a last goodbye. Who needs TV?

POST SCRIPT:

On 24 February 2010, Gordon Brown, the British Labour Prime Minister made a statement in the House of Commons giving details of how successive UK Governments had supported child migration to Australia, Canada, New Zealand, South Africa and Zimbabwe. He apologised to these children who were robbed of their identities and childhood when authorities ‘instead of caring for them, paid no heed to their cries for help.’ The apology was supported by all sides of the House. Canadian petitions have so far failed to obtain a similar apology from the Canadian Prime Minister.

The Memorial Plaque for the Hazelbrae children shows they were still being received up to 1923. The scheme to send ‘orphans’ from UK to ‘the Colonies’ did not entirely cease until the 1970s.

RIP

Notes & Bibliography

Hodges, Shirley, ‘Bristol’s Pauper Children: Victorian education and emigration to Canada.’

I am grateful to Lynette Bartlett Sutton for sharing her original research. It appears here with her kind permission.

An article similar to this one will appear in a forthcoming Bristol & Avon Family History Society Journal.

[1] Thomas had left home by this time.

[2] Western Daily Press, 31.10.1902

[3] Ibid, WDP 5.9.1903

[4] Mary Leighton, ‘The Victorian Girl’ whose story is told elsewhere in this blog was maliciously told at some point ‘Your father killed your mother!’ and believed all her life, incorrectly, that her father was a murderer. She never knew his name (blank on her marriage certificate) and though she vaguely remembered her sister who had died in the Home, all memory of the aged grandmother who had tried to look after her, had been erased.

[5] My Dad, Jack Pillinger, (change the letter!) would often say, loving the vicarious notoriety, “They ‘ud often call I Public Enemy Number One.”

[6] Like many former Kingswood people, I remember seeing ‘the Reformatory Boys’ marching in ranks to Holy Trinity Church for Sunday morning service.

[7] I cannot say what the general conditions were like, though I knew a person who had been a House Mother there. I had the misfortune to be stuck with her as a travelling companion when hitchhiking round Europe in 1957. She would still easily make the list of the ten most obnoxious people I have ever met. She called her erstwhile charges “Filthy little bleeders. Should have been stifled at birth.” Now that such establishments are at last under scrutiny, I wish I had investigated fully but that time I would have had no idea how to go about it.

Leave a Comment