The majority were young men all convicted by the Bristol courts for (usually) petty thefts committed in the city. Most had waited years in Newgate gaol, and suffered further imprisonment and hard labour in the hulks before leaving for their eventual destination. A few were Bristolians ‘born and bred’ though others came from farther afield. One, John Barry, was black. It is quite likely the older men, those born about 1760 or before left wives behind.

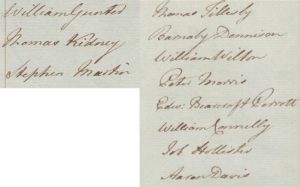

The ‘Bristol’ men brought from the hulk ‘Censor’, to the ‘Alexander’, 6 January 1787.

With the logistics of the enterprise settled, the convicts were distributed to their allotted ships in 1787, the Bristol men divided between Alexander (January) and Friendship in March. Even before they sailed, one of their number was lost; whether from accident, escape attempt or suicide, William Wilton went overboard from Alexander and was drowned in the murky waters of Portsmouth Harbour. The Alexander, the largest of the Fleet, with all male inmates, had the worst death record: sixteen died from ‘gaol fever’ when still at anchor and another fifteen succumbed at sea. For the whole Fleet, which was well organized, the number of deaths was calculated at forty eight, a modest number in comparison with the next, the horrific ‘Death Fleet’.

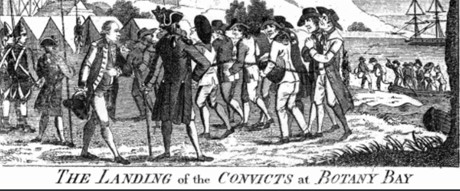

On 13 May 1787, eleven ships carrying more than 700 men, women and children left Portsmouth. Between that day and 1868 when the system ended, more than 162,000 people were transported to Australia.

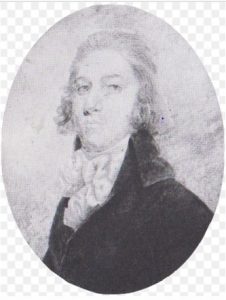

Lt. Ralph Clark, c1762-94

https://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/clark-ralph-1898

For Friendship we are fortunate in having Ralph Clark, a Lieutenant of Marines, a man in his mid to late twenties, whose Journal has survived 1787-88 and 1790-92. He was desperately homesick during the voyage and pined for his wife Betsey Alicia and baby son; his lamentations may qualify him as the original ‘whingeing Pom’, though he perked up considerably in the later Norfolk Island section when he was given responsibility at Charlotte’s Field. This may also have had something to do with his female companion, the mother of his daughter, who gets no mention in his narrative. In the opening pages of the Journal is ‘the list’ in which he identifies Friendship’s human cargo on 11 March 1787 by name, age, occupation, crime, where tried, length of sentence and origin where known.

At sea, the convicts lived below decks in cramped, foul, conditions, prey to rats, cockroaches, bed bugs, lice and fleas and under stern discipline. Some were caged. At the start of the voyage they were allowed on deck to exercise but as the ships progressed south, the diversion ceased. A sudden tropical rainstorm could soak their clothes, for which they had no change.

The Fleet arrived in Australia between 18 & 20 January 1788.

First Fleeters: The Bristol Men

NB: to avoid repetition ‘Quarter Sessions’ is abbreviated to QS. ‘Newgate’ is the Bristol gaol, not to be confused with London’s prison of the same name.

* Those marked with an asterisk went to Norfolk Island 1790 and survived the wreck of the Sirius.

BARRY, John, c1768-1788, Friendship & *KIDNER, Thomas, alias Kidney, 1767-? Alexander.

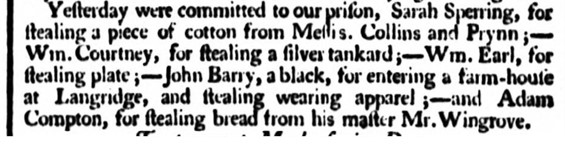

These two young men knew each other at least from 19 September 1782 when a report appears in the Bath Chronicle:

‘Thursday were committed to Newgate, John Barry, Wm. Northcutt and Tho. Kidney [sic] for stealing 4 pieces of Irish linen, value £6, the property of Mr. William Overend, and Elizabeth Pollard for receiving one piece of Irish linen knowing it to have been stolen.’

(The merchants, William Overend & Co, were active in Bristol’s infamous ‘Africa Trade’.)

Kidner, judged to be the ringleader of the group, was sentenced to transportation for seven years ‘beyond the seas’ while the others, convicted of ‘inferior offences’ received ‘lesser terms of imprisonment and to be publicly whipped.’

Thomas Kidner was baptised at South Petherton, Somerset on 16 November 1765, the son of James, a farm labourer, and Mary.

Following his court appearance, young Tom, who was still only 16 when convicted was taken to Newgate where he spent four years until transferred to the Censor hulk at Woolwich. On 6 January 1787 he was removed to Alexander, sailed with the First Fleet in May 1787 and arrived in January 1788.

Conditions in the colony were harsh, punishments brutal. In 1789 he was sentenced to 150 lashes for ‘obtaining necessaries’ from a marine, Mark Hurst. (The next year, when the colony had even less food, the same Hurst was charged with the theft of rice from the communal store. He was sentenced to 500 lashes. He survived and returned to England on the Gorgon in 1791.)

In 1790, Kidner was sent from Botany Bay to the alternative settlement, the remote Norfolk Island, a dot in the ocean, about a thousand miles from Sydney. He lived there for 15 years, during which time he married Jane Whiting, who, aged 14, had been transported on the female ship, the notorious Lady Julian. They had two children. By 1807 they were resettled in Tasmania though they later separated. The date of Thomas’ death is not known but Jane died in Hobart in 1826 at the age of fifty.

In 1790, Kidner was sent from Botany Bay to the alternative settlement, the remote Norfolk Island, a dot in the ocean, about a thousand miles from Sydney. He lived there for 15 years, during which time he married Jane Whiting, who, aged 14, had been transported on the female ship, the notorious Lady Julian. They had two children. By 1807 they were resettled in Tasmania though they later separated. The date of Thomas’ death is not known but Jane died in Hobart in 1826 at the age of fifty.

Almost two years passed before John Barry next appears in the news, in the Bath Chronicle, 19 August 1784:

John was one of a small black population who lived in Bristol and Bath in this era. A scant reference in the same newspaper, 31 March 1785, not mentioning his colour, states that he and others were tried for ‘sundry thefts’. By the end of the year he was in trouble again, and on 23 November 1785 at Bristol QS he was sentenced to transportation for seven years.

On 11 March 1787 he went aboard Friendship, one of the miniscule number of black convicts on the First Fleet; he is listed by Ralph Clark as ‘Jno Barns’, aged 19, no trade, convicted for the theft of three pairs of stockings.’

He died on 10 March 1788 shortly after arriving at Sydney Cove.

BRICE, William, c1771 – ? Friendship. For years outraged citizens of Bristol had been complaining about the number of seemingly feral boys who lived on the streets, causing nuisance and mayhem; nobody as yet thought these destitute children might be in need of care and protection. (Orphanages, Training Ships and the removal of poor youngsters ‘for a better life in Canada’ would come with the Victorians.) William was only fourteen when sentenced to seven years on 11 February 1785 for taking a looking glass, from a shop in St Peter Street. (Size unspecified; if this was a small hand glass, the theft was pitiful; if large an encumbrance.) Unfortunately his sentence of seven years was a formality: he had been whipped for a previous offence in 1784.[1] He had already been locked up for two years when he arrived aboard Friendship. His birthplace can only be guessed at, but it is worth noting that a William Brice, ‘father unknown’, the son of a single woman, Mary Nowell, was baptised at North Petherton on 7 July 1770, a stone’s throw from the village Thomas Kidner called home. If he is the same, then this young Billy Brice would fit the general pattern of the unwanted urchins, especially if orphaned. Aboard the Dunkirk hulk his behaviour was ‘tolerably decent and orderly’.

Brice survived the ordeal of the voyage, and is named in victualling lists for 1788. In 1789 he was called as a witness when one convict accused another of making threats against him. He then disappears from the records. Various alternatives have been suggested: he ‘left the colony in 1792 when his sentence expired’; he ‘found a ship and worked his passage home’, or ‘he was lost in the bush’.

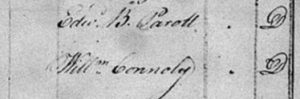

*CONNELLY, William, c1760 –? & *PERROTT, Edward Bearcroft, c1760-? transported by Alexander, they were jointly charged with the theft of clothes from the Swan Alehouse in Temple Street. They were found guilty on 3 February 1785 at the Bristol QS and sentenced to 7 years. They were sent to the Ceres hulk, where they remained until they embarked with Alexander, arriving in Sydney in January 1788.

William Connelly married fellow First Fleeter, Elizabeth Thomas, (Prince of Wales) at Sydney Cove on 19 October 1788; their son William, who was baptised on 5 July 1789, lived for only three months.

Connelly and his wife were sent to Norfolk Island on the Sirius in March 1790 and survived the shipwreck. By March 1791 they were living on a one acre lot at ‘Sydney Town’ on the island and by the end of the year Connelly was a member of the night watch. In May 1792 he was selling surplus grain and meat to the Government stores.

Leaving his pregnant wife behind, he boarded the Sugar Cane, for India in October 1795, presumably to work his passage. This three-decker merchantman, having recently landed Irish convicts in Botany Bay obtained a contract from the East India Company in Calcutta and returned to London via Madras, St Helena and Kinsale. She later became a slave ship.

It is unknown whether Connelly stayed with the ship all the way home. Elizabeth Connelly who remained in Australia found another man, James Waterson with whom she was living in 1796.

Edward Bearcroft Perrott, alias Parkins, likewise arrived at Cascade, Norfolk Island, in March 1790 and lived there with Ann Read who was serving life ‘for assault and theft on the King’s Highway’. On 30 September 1791, a convict called Thomas Seal absconded and was absent from work until 10 o’clock on the night of 10th October when he was caught scavenging in Perrott’s garden. Seal, weak from ten days in the bush, was flogged with 49 lashes: when, as it is quaintly put in other cases, he could probably ‘bear no more’.

‘Mates’. Perrott and Connelly were still side by side on the Norfolk Roll.

With his time served, Perrott left the settlement in January 1793 aboard the Philadelphia, bound for China.

*DAVIS, Aaron, c1761-c1813, & CROWDER, Thomas Restell or Risdale, c1758-1824, both Alexander, were jointly charged and found guilty on 29 March 1785 at Bristol QS for stealing watches and rings from a John Gunning.

Davis, whose case was immediately proved, spent a few months in Newgate before being transferred to the Ceres hulk where he remained until taken to Alexander for transportation. He arrived in New South Wales in January 1788. Perhaps originally a baker, he was making bread for the Sirius before leaving for Norfolk Island in 1790. Described ‘very industrious’, he cleared 24 rods of a one-acre site where he supported two females, Mary Walker, the mother of three of his children, and a four year girl, Sarah Lee. His bakery prospered and he began a modest business. In 1804, his son Francis, by Elizabeth Hosier was born. With his time served by 1805, he left his enterprise in the hands of James Mitchell, by then the husband of Sarah Lee. It is not known whether Aaron ever returned to Bristol, but England, wherever he was, did not live up to his expectations. He suffered financial losses and was disillusioned by 1813 when he issued a petition to return to New South Wales with his two daughters. Unfortunately, he died before his case could be finalised.

Aaron Davis’ encounter with Thomas Restell Crowder was apparently fleeting – they did not know each other at all, (he said), though he had seen Crowder in the same auction room before they were arrested.

Crowder was a Londoner, born at St Martin-in-the Fields, a career criminal with ‘previous’. An unsuccessful burglar, his conviction, aged 25, in 1783 at the Old Bailey under the heading, ‘Newgate, London’ was for intent to steal from John Bradford at St Mary-le-bone:[1]

He received the mandatory ‘death recorded’, commuted to transportation. The British Government, in cloud cuckoo land, expected ‘normal service would be resumed’ after losing the war, and in due course, Crowder was taken from his prison to the Mercury, bound ‘for America’. Thus in 1785, he became one of the ‘Mercury Mutineers’. (see Chapt. 1) He evaded capture and escaped to Bristol where allegedly he fell in with a local lad, Aaron Davis, and was charged with ‘thefts of a very large amount’. Aaron, the lesser party, was immediately sentenced to transportation, but judgement on Crowder was deferred; he was indicted for another burglary as well as the mutiny. When these cases were heard, he was sentenced to death twice, and was in the condemned cell awaiting the ultimate turn off when the Recorder became uneasy about evidence given by an informer. Crowder was reprieved on both counts. By now, having escaped the hangman three times, his sentence was commuted to transportation for life, again ‘to America’. This, of course, did not happen. He was put on board the Justitia hulk and on 6 January 1787 was delivered to the Alexander in readiness for Botany Bay.

He and his wife Sarah Davis were sent to Norfolk Island on the Supply in February 1789 where he became an overseer and was recommended for good behaviour by Lieutenant Governor Philip Gidley King. He was emancipated in 1782 and became a settler. In January 1794 he became involved in a fracas with a sergeant and was sent to Sydney in irons. He returned to the island shortly afterwards which suggests he was exonerated. After the death of his wife he lived quietly cultivating his land and in 1809 went to Tasmania (then Van Diemen’s Land) with other islanders. In 1813 he became Superintendent of Convicts with a salary of £50 per annum. On retirement he was superannuated for services rendered. He died in Hobart on 28 November 1824, ‘a much respected former government employee’.

His obituary appears in the Hobart Town Gazette, 3 December 1824:

‘DIED. On Sunday last, in his 67th year, at his residence in Elizabeth-street, Mr. Thomas Restell Crowder, 36 years an inhabitant of these Colonies, and several years Principal Superintendent of Convicts, much lamented and regretted by his friends.’

The full history of Crowder’s life in Australia is admirably documented online by John Boyd of the ‘Fellowship of the First Fleeters.’

DENNISON, Barnaby, c.1758–1811, Alexander, was found guilty on 30 April 1783 at Bristol for stopping Richard Jones in Castle Precincts with ‘intent to rob’. Sentenced to 7 years transportation he was taken to the Censor hulk, until he embarked on the Alexander in 1787.

After arrival in the colony he was charged, with a seaman, Walter Ellis, and seven others for rowdiness, ‘making a noise at an improper hour and disputing the authority of the Guard’, Sergeant (Richard) Clinch, and his escort, the second part of the offence being far more serious. Ellis was sentenced to 100 lashes, Dennison to 50. The rest escaped with reprimands.

In February 1800, evidently reformed, he was sworn in as a constable at the Dawes Point district and by 1806 was working as a stone mason. He received a 30 acre grant of land at Toongabbee in Sydney.

Barnaby Dennison died at Sydney General Hospital and was buried on 28 April 1811, his age given as 58. Clinch died in a drowning accident in 1799.

*ELLIOT, Joseph, alias Trimby, c1767-1836, Friendship, a son of Richard Elliot and Christian Trimby (married Horningsham, Wiltshire in 1755). Aged 17 he was sentenced to seven years transportation at Bristol QS on 24 November 1784 for the theft of a tobacco pouch. His early life prior to removal to the hulk has been told in Chapter 2, ‘The Inhabitants of Newgate’. He is listed by Ralph Clark, 1787, as ‘aged 20, a gardener, theft of a pocket book’. Clark mentions him again in the Journal entry, 18 December 1790, as ‘one of the carpenters’ on Norfolk Island, 18 December 1790, for

‘shirking his work three different times [……] and would not be Quite [sic] when I orderd him.’

He was brought to Town where Major Ross sentenced him to 100 lashes, but he could only bear 73. He was then ordered him back out to Charlotte Field where Clark was in command.

On Norfolk, Joseph Elliot married Elizabeth Sieney, a former acquaintance from Bristol who was part of a loose network of young people who were in and out of Newgate. Elizabeth, transported on Lady Julian, was the sister of James, a fatality of the wicked Second Fleet.

The full horror of Joseph’s life in Australia, almost the exact opposite to that of Thomas Crowder can be found online in a biography, ‘Trimby’s Travels’, by Sister Andrea Myers of the Fellowship of the First Fleeters. She tells how that first 7 year conviction stretched to 47 years of imprisonment and barbaric punishment, 1784-1831. Myers says: ‘…….all because of an empty pouch. Joseph served his time in every way.’

Farley, William, see Neal[e], James

*FINICY, Thomas, alias Fillesey, Tillesey, Finnesy, 1758 – c1795? Alexander, was indicted as Tillesey but in the colony was more often recorded as Finicy. He was found guilty at Bristol on 29 April 1783 for the theft of a pair of shoes with buckles and sentenced to 7 years transportation. After about a year in Newgate, he was sent to the Dunkirk hulk and remained there until discharged to Alexander to await transportation. He arrived in Sydney in January 1788.

From the start of 1789 he was continually in trouble. On 9th February at Port Jackson he received 50 lashes for being absent from work for three days; on 3rd October he was reprimanded for stealing a pair of shoes belonging to Richard Partridge, which he said was just a prank. John Coen Walsh, a member of the Night Watch spoke up for him, saying he had never known Finicy to steal. The matter was written off but it marked him out and on 7th November his penalty was 100 lashes ‘in the usual manner’ for attempting to break open a box belonging to George Fry. On 16 February 1790 he was given another twenty five for neglect of work. In March he departed on the Sirius for Norfolk Island. Sirius was shipwrecked in the harbour and though there was no loss of life, the ship and much of the stores were lost.

On the 15th May ‘Finnesy’ stole a cabbage from Lieut. Creswell’s garden, and was on the run for twelve days. He was punished by having his weekly flour ration reduced from three to two pounds for ten weeks and to work in irons for that time.

By 1 July 1791 he was subsisting on a Queenborough lot with 66 rods cleared and sharing a sow with William Davis and Jane Read.

He left Norfolk Island on the Atlantic in September 1792 and was in Port Jackson until 24th October when he was marked ‘off stores’. He was either dead or managed to work his passage home. In any event he is never heard of again.

*GUNTER, William, alias Gunther, c1764- ? Alexander, tried at Bristol, 4 August 1783, was sentenced to 7 years transportation for ‘felony’. He spent over two years in Newgate before he was taken to the Dunkirk hulk in late 1785 where his behaviour was ‘tolerably decent and orderly’. He sailed with the Alexander and arrived in January 1788. He was sent to Norfolk Island in March 1790 aboard Sirius.

On 20 August 1791, Ralph Clark records

‘Punish’d Isaac Williams with 100 Lashes and William Gunter with 59 Lashes – Gunter was also orderd to receive 100, but could not Bear more than the 59 – they both were punishd for Neglect of Duty.’

And on 17 October 1791:

‘I punished Wm. Gunter with 50 Lashes at Phillipburgh for quitting the duty he was orderd on and going into the Woods and Staying there a week. This said Gunter is a very bad Subject.’

Gunter was working as a labourer for William Fisher in May 1794 and with his sentence completed, he left the colony, and is presumed to have signed on as a seaman aboard HMS Daedalus, which was returning home from a three year voyage to the South Seas.

HOLLISTER, Job, c1766 -? Alexander, was indicted for the theft of tobacco from a shop in Castle Street, Bristol on 31 December 1784. He appeared at the QS in February and was sentenced to seven years transportation. The Gaol Delivery Fiat 30 April 1785 states that three others received the same sentence, John Wisehammer, James Neale and William Farley. He was aboard the Ceres hulk by 7 January 1786 and then discharged to Alexander in January 1787 in preparation for the voyage. He arrived in Australia in January 1788.

He kept his head down in the Colony and is only mentioned once, ‘off stores’ by July 1793, when he is believed to have signed aboard HMS Daedalus with William Gunter..

Jones, Thomas, see Leary. Jeremiah

Kidner, Thomas, see Barry, John

LAMBETH, (Lambert) John, 1763-88, Friendship, a blacksmith, born in Warwickshire, believed to be the son of John & Catherine Lambert baptized at Fillongley, 7 April 1763. He was convicted at Bristol on 29 March 1785 for the ambitious theft of ‘£3.7s and a £5 promissory note’ though Ralph Clark in 1787 states the sum to be £1.19s. His conduct aboard the Dunkirk hulk was ‘tolerably decent and orderly’. He survived the voyage but died a few months after arriving in the colony. He was buried at Sydney Cove on 2 July 1788 as John Lambert.

*LEARY, Jeremiah c1765-c1807, & *JONES, Thomas, c1765-c1805, Friendship, were convicted of ‘housebreaking’, which amounted to the theft of a pair of gloves from a Mr. Benjamin Montague, on 30 March 1784. A mandatory ‘death recorded’ sentence, was commuted to 14 years transportation for each man. The severity of the term suggests they had previous ‘form’.

Leary, possibly Irish by his surname, and Jones spent a few months in Newgate followed by the Dunkirk hulk on 18 August 1785 where they remained until February 1787 when they were delivered to the Friendship. Leary (spelt ‘Learly’ by Ralph Clark) was then aged 22. He arrived at Sydney Cove in January 1788 and was sent to Norfolk Island on the Sirius in March 1790. Soon afterwards, he was forced to ‘run the gauntlet’ by fellow convicts for theft, a bloody punishment, recorded as ‘severe’. He subsisted on the island until 1807 when he was marked in returns as ‘dead’.

Thomas Jones, a bricklayer from Warwickshire, also 22, as recorded by Clark, likewise went to Norfolk Island, where he disembarked at Cascade, 14 March 1790. He ‘received rations’ until 1795 with no other information until he was ‘off stores; sentence expired’ in February 1805. By 7th June that year he was dead, recorded by Rev Fulton as ‘Jones, freeman’.

*MARTIN, Stephen, c1746/8 -1829, Alexander, was sentenced on 30 April 1783 at Bristol QS to seven years transportation. Various transcribers have read his crime as ‘the theft of a cann (sic) and a pair of boots and spurs’, which as a combination made no sense. Then only recently I discovered the truth in Stephen’s fine online biography by Kathleen Rutherford.

*MARTIN, Stephen, c1746/8 -1829, Alexander, was sentenced on 30 April 1783 at Bristol QS to seven years transportation. Various transcribers have read his crime as ‘the theft of a cann (sic) and a pair of boots and spurs’, which as a combination made no sense. Then only recently I discovered the truth in Stephen’s fine online biography by Kathleen Rutherford.

(It was a cane, of course, not a can. So Stephen was immediately transformed into an aspiring dandy, dashing in his boots, spurs, and walking cane. All he needed was an outfit to match, perhaps Thomas Finicy for the buckles, Peter Morris, the breeches and waistcoat, John Barry for the hose and Jeremiah Leary, the gloves!)

The Coach and Horses still currently in operation, 2022, is about 10 miles from Reading on the Bath Road to London.

Stephen’s Bristol story began three years before when he and his brother William arrived in the city from Cornwall to try their luck. They had been working a mere week as porters for William James when they were accused by the son of the house, John Sartain James, of taking two chests of tea, valued at £60 from a Jacob Street warehouse and giving instructions for it to be delivered to an inn, the Coach & Horses at Meacham, near Newbury, Berkshire. This seems to have been a significant theft of a fashionable commodity, which makes the lenience of their sentence, one year apiece in Newgate and fined a shilling, all the more suspect. Many people had been hanged for less.

So why did they get off so lightly? It is implied that Mr. James was a merchant, though his obituary in a Bath newspaper tells a different story. He was

‘many years carrier from this city, London and Exeter which he had some time since declined in favour of his son, John Sartain James.’[1]

The Coach and Horses is about 10 miles from Reading on the Bath Road to London. Instructions must have been given for delivery to the address, a pub probably a frequent port of call on the James’ route. Somebody was clearly up to something but the Magistrates could not quite decide what, so the Martins took the fall: ‘Give ‘em a year each to be on the safe side.’ For William it was particularly disastrous. He caught smallpox in Newgate and died.

The boots and spurs for which Stephen was convicted in 1783 were valued at ten shillings, and belonged to Henry Payne of the Queen’s Head. Elizabeth Yandell of another pub, the Plough in West Street, also chipped in saying he had stolen a cane from her which she valued at 40 shillings. This was either a spectacular piece or more likely she said the first sum which popped into her head.

So then Stephen was on his way back to Newgate and a couple of years later to the Censor hulk on the Thames. On 6 January 1787 he was transferred to the Alexander.

Once in the colony he received the obligatory flogging, 25 lashes, for neglect of work, in February 1789 and a more severe 50 in November for theft. He was sent to Norfolk Island in 1790, where the next year he married Hannah Pealing in a mass wedding involving ten couples. He received a grant of land and became relatively prosperous: he had an employee and sold surplus grain to the government. By 1805 his little house was valued at £15. He was widowed when he left Norfolk in 1808, with his daughter, his only child, when the islanders were re-settled in Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania).

Stephen died in Tasmania aged 81 in 1829.

*MORGAN, Richard, c1761-1837, Alexander, is believed to have been born at St Philip and St Jacob, a large parish east of Bristol the majority of which was then in the county of Gloucestershire, hence Richard being tried 40 miles away in the county town. On 23 March 1785 he was convicted of stealing a watch and demanding a promissory note with menaces from an un-named man. He was sentenced to transportation for seven years and transferred to the Ceres hulk on the Thames in June the same year. He embarked for New South Wales on the Alexander in January 1787.

In Australia he became re-acquainted with Elizabeth Lock, (of the Lady Penrhyn), who he had met when both were in Gloucester Gaol. The couple were married in Sydney on 30 March 1788, two months after their arrival.

Sadly, the romance did not last. They were sent to Norfolk Island in 1790 on different ships, Dick on Supply, Liz on Sirius. On arrival they went their separate ways.[2]

The later history of Richard Morgan, his second wife Catherine Clark, and their seven children is told in detail online by Cheryl Timbury; Richard is also ‘the hero’ of a novel, ‘Morgan’s Run’ by Colleen McCullough.

He was buried on 26 September 1837 at Clarence Plains, Tasmania, his age given as 78.

MORRIS, Peter, c1759-? Alexander, was found guilty on 12 July 1784 at Bristol for the theft of breeches and a waistcoat. He was sentenced to 7 years transportation, and followed the pattern of Newgate, Ceres and the Alexander, arriving in Sydney in January 1788. He was mustered aboard ship and did not die during the voyage, but there are no records of him in the colony and it is thought that he may have been one of eleven men recorded as ‘absconded’ soon after landing. (Now there’s a story for a novelist and a Netflix series!)

Perrott, Edward Bearcroft, see Wm. Connelly

NEAL(E), James, c1769- ? & *FARLEY, William, c1770-?

Two teenagers convicted together at Bristol on 10 February 1785 for the theft of two pounds of sugar and sentenced to seven years transportation. From Newgate they were transferred to the Censor hulk and then to Friendship.

Neale, recorded by Ralph Clark as ‘Jas. Neel’, was by then eighteen. On 6 March 1789, he and six other convicts absented themselves from their work at a brick kiln, left the confines of the settlement with the intention of looting fishing tackle and spears from the nearby Eora tribe. One account says there was a melee in which one of the convicts was killed and the rest injured. They were rounded up and each sentenced to 150 lashes and to wear leg irons for a year.

The bloody event was designed to show the indigenous people British ‘fair play’; that wrongs committed by either side against the other would be punished with equal severity. An indigenous Australian, who had been in the settlement about four months, was forced to witness the flogging. Not surprisingly, his reaction was ‘disgust and terror’.

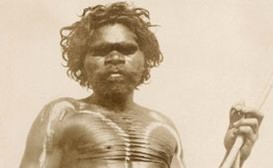

The man was Arabanoo, the first ’aborigine’ (now an offensive term) to live among the arrivals, if it can be called ‘living’, for he had been kidnapped by a scouting party and brought to the settlement tethered and handcuffed. Originally he seemed delighted with the handcuffs, possibly thinking they were ornamental bracelets but became ‘furious’ when he knew their true purpose. The abduction had been deemed ‘essential’ by Governor Phillip, with the idea of teaching the captive to speak English so that he could act as a go-between between the occupiers and the occupied, and report ‘the advantages of mixing with us.’ (Look how civilised we are!) Arabanoo was not a particularly adept student and it may be assumed from his terrified reaction that the gross spectacle he was compelled to watch had the opposite effect to what was intended.

There is no further mention of Neale and he may have died from the flogging or from smallpox. Arabanoo himself succumbed on 18 May 1789 aged about thirty. Col. David Collins wrote an obituary note:

No contemporary drawing of Arabanoo appears to exist. Acknowledgements for the above to https://www.britannica.com/topic/Australian-Aboriginal/Leadership-and-social-control

‘His death was to the great regret of everyone who had witnessed how little of the savage was found in his manner and how quickly he was substituting in its place a docile, affable, and truly amiable deportment.’

The smallpox spread to the local population who had no immunity to the new disease and about 2,000 died.[1] In addition, convicts would soon launch vigilante attacks on the same clans who lived in the vicinity of Botany Bay.

Arabanoo was followed by other captive ‘natives’ including the notable Bennelong whose fascinating story can be read on Wikipedia.

The Hampshire Chronicle had a strange contemporary view concerning the indigenous inhabitants of Botany Bay. (11 Dec. 1786).

William Farley, listed by Clark as Fairly, was about 15 when originally sentenced. He accompanied James Neale to Newgate, Censor and Friendship. He went to Norfolk via the Supply in 1790, and sustained himself on a one acre plot. By 1792 he was off stores and working for Norfolk Island settlers. He left Australia in 1793 to work his passage home to England as a seaman on the return journey of the convict ship Kitty.

WILTON, William, alias Whilton, Wilson, c1741-1787, at 43, was the oldest of the Bristol men. He was convicted at the QS on 12 July 1784 for the theft of 18 turkeys from a Mr. Ward. His death sentence was commuted to seven years transportation. Before the Fleet sailed he fell overboard from the Alexander and drowned 28 March 1787. As the prisoners were heavily ironed he would have had little chance of saving himself.

*WISEHAMMER, John, c1772-? Friendship. After his earlier misadventures in Bristol, (see Chapt.2) John was convicted on 10 February 1785 for stealing a ball of snuff. This resulted in a sentence of seven years transportation, a final sojourn in Newgate and removal to the Dunkirk hulk where his behaviour was ‘tolerably decent and orderly’. When he was delivered to Friendship in 1787 Ralph Clark recorded his name as ‘Jno Wisihamer aged fifteen’. This is not the only time he is mentioned in the Journal. On Friday, 10 December 1790, on Norfolk Island, Clark wrote

‘walked out to Charlotte Field twice – Jno Nowland and Wisehammer two carpenters were punished out there for neglecting there work – the former received the whole of his punishment, 50 Lashes but Wisehammer could only bear 8 Lashes; the Surgeon said he could not bear more he fainted away twice.

‘Saterday, 11th – went out to Charlotte Field before breakfast which I carried with me. Returned to dinner – nouland and wirehamer two Convict Carp. Which were punishd Yesterday for Neglect of of duty have not been at work since – Reported them to Major Ross at my Return who orderd the Store Keeper to Issue only half allowance to them.’

On the other side of the world John met an old friend, Shuke Milledge (Lady Julian) who he had known in the ‘good old days’ at Newgate. They moved in together on the island. Shuke will have her own chapter, so we shall meet John again.

Clark and Wisehammer appear as characters in Thomas Kenneally’s novel, ‘The Playmaker’, based on real life events, and subsequently dramatised by Timberlake Wertenbaker as ‘Our Country’s Good’. The fictional Wisehammer bears little resemblance to his factual self.

Statistics: Why were the Bristol men transported?

Eight were convicted for stealing men’s apparel and accessories including breeches, a waistcoat, boots, buckled shoes, spurs, gloves and a walking cane. This was a complete surprise to me. Perhaps their own clothes were in rags, or being young, they had aspirations of cutting a dash. The remainder were convicted of a wide variety of thefts: jewellery/watches, money including ‘promissory notes’, tobacco/snuff, 18 turkeys, two bales of linen, a looking glass, an empty pocket book, and simply ‘a felony’. Of these two were additionally charged with mutiny and of threatening violence. One attempted a street ‘mugging’ without success.

Almost all seem to have had a previous court appearance; some of these had been ‘whipped’.

What came later?

One died before the Fleet Sailed

One absconded on arrival in 1788; One similarly went missing in 1792. It is probable both soon died in the vastness of the Bush even in the unlikelihood they were found and nurtured by friendly tribes.

Three died within hours, days or months of their arrival.

Seven left the colony when their time expired, several in named ships to work their passages home. Out of these one definitely succeeded but was so disillusioned after a few years in England he petitioned to return to New South Wales.

Nine remained in the colony with varying success, running the full gamut from premature death (well before sentence was completed), to a lifetime of punishment, even up to respected government employee.

The last word : A cruel joke:

- On Sat 26 January 1842 The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiserreported

- ‘The Government has ordered a pension of one shilling per diem to be paid to the survivors of those who came by the first vessel into the Colony. The number of these really ‘old hands’ is now reduced to three, of whom, two are now in the Benevolent Asylum, and the other is a fine hale old fellow, who can do a day’s work with more spirit than many of the young fellows lately arrived in the Colony.

- ‘The names of the three recipients were not given, and is academic as the notice is false, not having been authorised by the Governor. There are at least 25 persons still living who arrived with the First Fleet, including several children born on the voyage. A number of these contacted the authorities to arrange their pension and all received a similar reply to the following received by John McCarty on 14 March 1842:

- ‘I am directed by His Excellency the Governor to inform you, that the paragraph which appeared in the Sydney Gazette relative to an allowance to the persons of the first expedition to New South Wales was not authorised by His Excellency nor has he any knowledge of such an allowance as that alluded to.” (signed) Deas Thomson, Colonial Secretary.

Supposing the above had not been a hoax, none of the Bristol men would have been eligible, as none were alive in 1842. Our most aged survivor was my imagined dandy, Stephen Martin who died in 1829 aged 81.

References:

[1] Felix Farley’s Bristol Journal, 13.3.1784

[2] Derby Mercury, 16 Jan. 1783

[3] Bath Chron 15.2.1787. ‘William James, London carrier, 76 Old Market’ is in Sketchley’s Directory of Bristol, 1775,

[4] For Eliz. Lock’s story, see Bristol Women below.

[5] Controversial. How smallpox arrived is a subject of much argument between historians.

Notes on sources:

I have drawn heavily on published research by previous historians:

Chapman, Don: 1788. The People of the First Fleet (1986)

Gillen, Mollie: The Founders of Australia: A Biographical Dictionary of the First Fleet (1989)

Mackeson, John F, Bristol Transported (1987)

The Journal and letters, of Lt. Ralph Clark 1787 – 1792 edited by Paul G. Fidlon & R.J. Ryan, published by the Australian Documents Library, 1981

https://peopleaustralia.anu.edu.au/biography/dennison-barnaby

https://www.fellowshipfirstfleeters.org.au/crowdersarahdavis.htm

https://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/crowder-thomas-restell-1939

https://www.fellowshipfirstfleeters.org.au/joseph_elliotttrimby.htm

http://www.fellowshipfirstfleeters.org.au/stevenmartin.htm

https://firstfleetfellowship.org.au/convicts/richard-morgan/

First Fleeters: the Bristol Women

There were only four Bristol women First Fleeters, all adults and all sailed on board the Charlotte. Their lives prior to the voyage are obscure and even thereafter they are seen mostly through the men with whom they were involved. I have tried to cement over these cracks with my imagination. From remarks made by Ralph Clark (Friendship’s Lieutenant of Marines and scribe) it seems they were not among the most troublesome. When the Fleet dropped anchor at Rio on the outward journey, 11 August 1787, he was peeved that ‘six of the very best women’ from Friendship had been exchanged for ‘six of the very worst’ from Charlotte. None were from Bristol.

The conviction of *Ann LYNCH, (c1746?-c1828?) brings to mind Dr Johnson’s infamous gibe ‘under the pretence of keeping a bawdy house, she was a receiver of stolen goods.’ She may have been one of the fairly numerous ‘Bristol Irish’, but Lynch could equally have been her married name. She is thought to have been about forty years old at the time she left England although her precise birthdate is unknown and similarly there is no known formal marriage. She is likely to have been a mother therefore Mary and John Lynch who stood beside her in the dock could have been her children. According to one report, (Bristol Journal, 25.3.1786) the goods which led to Ann’s downfall were valued ‘above the sum of one shilling’. She was sentenced to transportation for 14 years, the harshness of which must mean that she was a habitual ‘fence’. Mary and John were charged with the theft of the same unnamed articles. If they were children this would suggest an ‘Oliver Twist’ situation where youngsters were sent out thieving by an adult. The boy, John Lynch was acquitted but Mary was ‘guilty ‘, sentenced to six months in the Bridewell and to be ‘twice whipped’ at the beginning and end of her term, a cruel sting to concentrate her mind. No comfort or companionship from Ann, her supposed mother, who waited separately in Newgate for the familiar transit, gaol to hulk to transport ship.[1]

Shortly after arrival in New South Wales, Ann began a liaison with a marine, Thomas Cottrell, which led to the birth of a boy also called Thomas, baptised at Port Jackson on 18 October 1788. Lynch and her infant were sent to Norfolk Island on the Sirius in March 1790. By 1794 with her relationship with Cottrell at an end, Ann and her son had moved in with another marine, Thomas Williams, a relationship which became permanent. (A man with good credentials, Williams had been Ralph Clark’s servant aboard Friendship.) Ann was given a conditional pardon in 1800 and in 1805, the family of three left the island, transferring at Port Jackson to the Buffalo bound for Dalrymple. (Thomas Cottrell was on the same ship!) Thomas Williams left the marine corps and as a settler was granted 127 acres in Sydney and began working as a miller. He later became an agent for Simeon Lord, a prominent merchant. By 1822, Ann was officially ‘free by servitude’. In 1825 she was admitted to hospital suffering from an unknown illness. At this time the address of the Williams family was South Head Road, Sydney, which gives an idea of the expansion of the settlement yet sounds so modern and homely that you could address an envelope there and think nothing of it.

The historical Old South Head Road goes through Sydney’s modern shopping centre and passes iconic Bondi Beach. It was originally constructed in 1811 in place of the bridle way which itself replaced the sea crossing to the Signal Station at South Head.

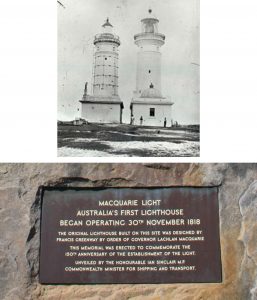

When writing a blogpost you never know who will turn up next. Francis Greenway, a talented artisan of Mangotsfield, Gloucestershire, a village just outside Bristol, pleaded guilty to a white collar crime, and came as a convict to Botany Bay in 1814. It is too much of a stetch to imagine Mrs Ann Lynch Williams would have encountered Greenway, but she definitely would have known his nearby lighthouse, the first to be built in Australia.

The Macquarie Light, old and new, side by side. The original, left, designed by Francis Greenway, convict and architect, began operating in 1818. Photo acknowledgment: Adam.J.W.C.https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=14787592

Ann died sometime between 1825 and the census of November 1828 in which Thomas Williams appears alone. His fate, and that of Ann’s son Thomas is unknown.

Mary CLEAVE or CLEAVER was baptised at Temple Church, Bristol on 12 November 1758, the daughter of John and Susannah. Her parents John Cleave and Susannah Westlake were married at Crediton, Devon in 1754. They had two younger children, John and Susannah baptised at Temple in the name of Cleave and it is likely there was another son James, who would be transported on the Scarborough of the notorious Second Fleet. Mary Cleaver was tried for burglary, convicted at QS on 5 April 1786 and sentenced to seven years transportation. After the customary sojourn in Newgate she was forwarded to the Dunkirk hulk at Portsmouth in wait for Botany Bay. On Dunkirk she found a protector, John Baughan.

Baughan, a cabinetmaker from Oxford, was aged about thirty, a married man with three daughters, aged nine and six year old twins. He was convicted for the theft of five wool blankets worth fifty shillings cut from a rack at New Mill in 1783. The Blanket Weavers of Witney were so outraged they advertised a £20 reward in Jackson’s Oxford Journal for the arrest of the thief. Four hundred handbills were printed and distributed. John was charged due to an unfortunate slip of the tongue by his wife Catherine through which the constable was alerted. John adamantly protested. He had bought the blankets lawfully, he said, for 28 shillings from the (usual, anonymous) ‘man in a pub’. He was prosecuted in the sum of £50 by the Weavers Company, found guilty with the death sentence commuted to seven years ‘to America’. From gaol he was put aboard the Mercury, and thus became one of the mutineers. (see Chapter 1)

His conduct on Dunkirk, no doubt still insisting on his innocence was ‘troublesome at times’. He had spent two miserable years in the hulk before Mary Cleaver arrived to give him solace. She became pregnant in early 1787 just before they went their separate ways in March, John to Friendship and Mary to Charlotte. Her son James was one of three babies born on the ship during the voyage.

John Baughan and Mary Cleaver were re-united in January 1788 on arrival at Sydney Cove, and on 17th February shared the happy event with nine other couples married in one ceremony by the Rev Richard Johnson. Whether the marriage was legal in John’s case is open to question. Tragically, joy was short-lived. Baby James died just over a month after the wedding and was buried on Friday 28th March. Another two infants, Charlotte and Charles followed. Charlotte died at 15 months and Charles buried aged seven weeks on 18 July 1790. There were no further children.

John’s skill as a carpenter and millwright were much in demand. In 1794 he erected a grinding mill in Sydney and was immediately commissioned to build another. According to David Collins, the Judge-Advocate, he was ‘an ingenious man’ despite ‘a sullen and vindictive disposition’. He built a ‘neat’ cottage with an attractive garden for himself and Mary at Dawes Point but in February 1796 became involved in a dispute with several marines who trashed the house. He died in Sydney on 28 September 1797.

Mary immediately started arrangements to leave the Colony; she arrived in Portsmouth in September 1800. It appears that like her fellow Bristolian First Fleeter Aaron Davis, England was not to her liking and by 1802 she was back in Sydney. In the muster of 1806 she was ‘Mary Borne per Charlotte, lives with Richard Harding’ a blacksmith. In 1808 the title of a property at 4 Hunter Street was transferred to her ‘in consideration of love and affection’ by her supposed brother, James Cleaver, who had seemingly made good in Australia from a less than promising start.

Back on 12 July 1787 the Bath Chronicle had reported on James’ career:

‘Monday last arrived in Bristol from Gloucester. Thirteen transports were lodged one night in the gaol and set off at 2 o’clock on Tuesday morning for Portsmouth in order to be embarked on board the ships bound to Botany Bay. Amongst the convicts was the noted Cleavor the famous housebreaker. About eight years ago he broke open a house without Lawford’s Gate of which he was convicted and received sentence of death but was afterwards pardoned on condition of serving on board one of his Majesty’s ships of war. He afterwards enlisted in a marching regiment but soon deserted, came to Bristol and followed his old practice of house-breaking, He having broke open about 42 houses in the parish of St James and parts adjacent he was tried on three different indictments last Assizes in Bristol and acquitted, was then removed to Gloucester and tried for breaking open a house in Thornbury, found guilty and received sentence of death but got his Majesty’s pardon on condition of transportation.’

In July 1819, this time for good, Mary and Richard Harding sailed for England aboard the Surry, (sic) and out of history. In October the same year brother James was living at Parramatta west of Sydney when he and his wife, another Mary Cleaver, witnessed the marriage of two ‘prisoners’ John Herbert and Ann Dudley. In 1828 John Roley, the district constable of Prospect (a Sydney suburb) listed 38 residents of whom ‘Mary Cleaver, tenant, (is) Free by servitude. This woman permits drinking in her house and is a general harbinger (sic) of Bushrangers.’[2] She must be James’ wife or widow.

*HANNAH JACKSON who was born about 1757 was found guilty on 28 July 1785 at Bristol, and sentenced to seven years transportation for stealing three yards of lawn, a cotton fabric used for making dresses. She remained in Newgate until forwarded to the Dunkirk hulk on 10 December 1785. She was removed to Charlotte in March 1787 and departed in May with the First Fleet. She was among those sent to Norfolk Island in 1790 on the Sirius and there met Joseph Dunnage, a veteran of the ‘Swift mutiny’, (see Chapter 1) Dunnage had been widowed in 1788 when his bride Sarah Parry, weakened by the voyage, died only a month after their wedding. On 3 October 1791 on Norfolk Island Ralph Clark reported in his usual matter of fact manner that ‘Dullage’ was

‘Punishd with fifty lashes for repeated Disobedience of Orders and neglect of Duty’.

Dunnage and Hannah returned to the mainland in 1793 and the following year Joseph was awarded 30 acres at Mulgrave Place. By 1800 he and Hannah were living together. They may have gained experience of agriculture whilst on Norfolk and at first things seemed to go well with two acres of wheat sown and another five made ready for maize. By 1802 eleven acres were cleared, whereupon there was a setback. It is possible that alcohol played its part and by 1806 Joseph had lost his farm and was subsisting on rented land, working in partnership with another man.

Matters continued to slide and in 1811 he was charged with distilling illegal spirits. He was sent to the Penal Settlement at Newcastle on 2 November 1813 via the Estramina.

Newcastle, formerly called Coal River was established in 1801 as the colony’s first place of secondary punishment. The unlucky inmates who called it ‘the Hell of New South Wales’ endured a miserable existence: back breaking work ten hours a day in the coalmines, logging, shingle splitting for roof tiles, or lime making on the shore, scanty rations and inadequate clothing. They suffered ‘dysentery in summer, the bitter cold in winter and chest complaints all year round.’ They lived under military discipline supervised by ‘trusty’ overseers where ‘King Lash’ ruled. Corporal punishment, for misdemeanours, as set by government decree, was meted out dutifully by successive Commandants, though some were more humane than others.

Governor MacQuarie who made an official visit in 1812, ’viewed the coalmines and the parts of the river where lime is made’ and pronounced his pleasure that the ‘useful settlement’ currently provided Sydney with Cedar, Coals and Lime; that higher up the river the soil was fertile and in time would support agriculture fit for the increasing population of the country. The convicts welcomed his award of a day’s holiday. Generally the only diversions were provided by ‘the many shipwrecks’ around the coast. (‘Wrecking’, passive, taking valuables from a ship which had foundered close to the shore was the mainstay of many a marginalized coastal community.)

The most dreaded punishment was kept for persistent offenders, who were sent to Hunter Valley, to dig oyster shells for lime burning. The smoke from the kilns affected the eyes and in worst cases caused blindness. Even so it was alleged that some prisoners deliberately exposed themselves in the hope bad eyesight would excuse them from the work. The boats which took the lime to Sydney were moored off-shore in water too shallow to allow docking nearer to land. The convicts waded out to the boats hefting sacks or baskets of lime on their backs, wet through at the mercy of the waves. Apart from the sheer drudgery they were easily burned by the lime, being without any form of protective clothing, often no more than a ragged shirt tied round the middle. At the end of each exhausting day they retired to huts where beds or blankets were non-existent. The men gathered seaweed from the shore and laid it inches deep on the ground, some bunking in together and dragging it over themselves ‘in short burying themselves in a dunghill to keep warm’.

The system ceased about 1822 when the source, the oyster shells, once so plentiful ran out.

Joe Dunnage was a prisoner until at least 1817, by which time he was over sixty. Following his release he worked as a labourer at Windsor. He and Hannah, who had survived alone during his absence, were reunited as man and wife, and both over 70, were counted in musters at Richmond, 1822 to 1828. No further records have been found for the couple.

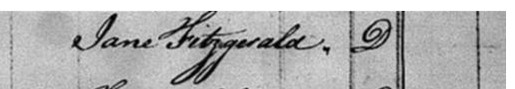

JANE FITZGERALD, c1757-1806, from her surname may have been another woman of Irish extraction. Nothing is known of her life until she was tried on 4 April 1786 for an un-named felony and sentenced to seven years transportation. At Sydney Cove in 1788 Jane began a whirlwind affair with a marine, Private William Mitchell, an Irishman from Bandon, County Cork, who had arrived with the Lady Penrhyn. Their sons, William and James, arrived on 9 October 1788, the first set of twins born in the colony. Sadly, baby James died aged three months and was buried on 15 January 1789 as James Mitchell Fitzgerald. Jane and her surviving son left for Norfolk Island, disembarking at Cascade on 14 March 1790.

William Mitchell came to the island in April 1791 on the Supply but left almost immediately for Sydney where he obtained his discharge from the Marines. He returned to Norfolk as a settler in November 1791.

Jane and William’s disjointed relationship does not seem particularly happy, for William departed again for the mainland in March 1793, aboard the Kitty, taking with him his son, William junior, now five years old. Men of course had paramount rights over their offspring, but this seems unbearably callous and cruel.

In Sydney William senior enlisted again. William junior joined the New South Wales Corps as a drummer on 25 June 1800 at the age of eleven.

Jane journeyed to and from Norfolk, probably to find her ‘husband’ and son, leaving the island in May 1795, returning in 1796, empty handed, and departed again in 1801. In 1806 in Sydney she is described as being self-employed with no children, in ‘a concubinage relationship’.[3] It is not known whether she saw her son before she died. She was buried at the Old Sydney burial ground on 2 September 1806.

The Mitchells, father and son returned to England in May 1810 when the NSW Corps was recalled.

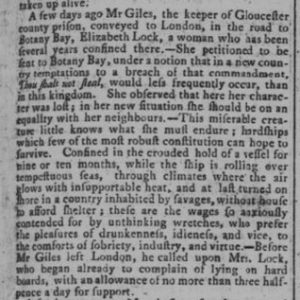

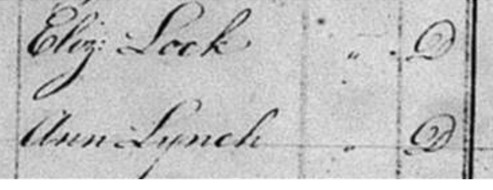

Elizabeth Lock appears next to Ann Lynch on the Norfolk Roll and though she was not convicted in Bristol, she is connected through her marriage to Richard Morgan, of St Philip & St Jacob, (one of the men in 4a). Liz Lock is notable – at least in my experience – for a unique request. She asked to be transported to Botany Bay!

She was born about 1763 and tried at Gloucester for two counts of breaking and entering, stealing a black silk hat, a black ribbon, a scarlet cloak and a linen cap. (The young men were not the only one with a fancy for nice clothes.) She was condemned to death for her crimes, and ‘pardoned’ on condition of ‘transportation beyond the seas’. She was still confined in Gloucester Gaol two years later when she met Richard Morgan. They were romantically linked between his conviction in the spring of 1785 and his transfer three months later to the Ceres hulk on the Thames.

Gossip about the proposed sailing to Botany Bay was common knowledge among all the prisoners. Petty and habitual crooks alike, even the most’ hardened’ were known to utter that they would rather be hanged and have done with it. Liz would have nine of it.

Perhaps in remembrance of their fond embraces, she put in an application to go into the unknown with the First Fleet. She appealed that ‘her character was lost’ and she would be more likely to adhere to the Commandment ‘Thou shalt not steal’ in a new country where she would be on a par with others in the same situation. This may have struck home with a zealot eager to prove the merit of the project, especially if it meant saving a lost soul from the clutches of Satan. So Elizabeth got her way, and was ‘conveyed to London’ in December 1786 by Mr. Giles, the keeper of Gloucester Gaol. If she hoped to be sent to the Ceres at Woolwich and a blissful reunion with her lover, she was disappointed. The Ceres was for men only. Liz was confined in the Bridewell with other women and children, picking oakum, arduous and tedious work separating bits of old tarred rope, needed to caulk gaps in the wooden ships. For ten or twelve hours a day. Definitely no picnic.

The Leeds Intelligencer issued a dire warning that worse was yet to come:

Leeds Intelligencer, 26 Dec 1786

This miserable creature, it thundered, little knows what she must endure; hardships which few of the most robust constitutions can hope to survive, confined in the crouded (sic) hold of a vessel for nine or ten months whilst the ship is rolling over tempestuous seas through climates where the air glows in insupportable heat, and at last turned on shore in a country inhabited by savages with house to afford shelter; these are the wages so anxiously contended for by unthinking wretches who prefer the pleasures of idlenes, drunkenness and vice to the comforts of sobrity, industry and virtue.

Mr Giles called to see the prisoner in her new quarters before he went home. With some hint of ‘I told you so,’ he reported that she was already complaining of lying on hard boards with only three halfpence a day for support.

Eliz: Lock & Ann Lynch listed beside each other on the Norfolk Island Roll

She had to wait six months before she sailed with the First Fleet (Lady Penrhyn) in 1787. Richard was on the Alexander. They were married in Sydney on 30 March 1788, three months after meeting again.

Sadly the (presumed) rapture did not last. The marriage may have already faltered by the time the couple arrived separately on Norfolk Island, Richard on Supply in January 1790 and Liz on Sirius two months later on 5th March. She disembarked on the 14th at Cascade before the wreck. By November, a marine of the 38th Company, Thomas Scully had arrived on the island as a settler and in April 1791 he was awarded a 60 acre grant of land at Bumbora Road. He and Elizabeth began a relationship and are recorded together in 1794. A year later Scully was selling off pieces of his plot to various others in preparation for leaving. One of the buyers was William Blatherhorn, the old mutineer, who had recently been recommended for a conditional pardon on the grounds that he had been a reliable overseer. A few years later he was made constable. Another ‘bad boy made good’.

Mr and Mrs Scully left Norfolk Island in 1795 aboard the Asia, an East Indiaman, for India and homeward bound.

The Asia by William John Huggins (Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

[1] Bath Journal 30.3.1786 states Ann’s ‘assistant’ as ‘Ann Obery’ with no mention of Mary & John.

[2] Paula J Byrne, ‘Criminal Law & Colonial Subjects’, 2003

[3] Gillen, Mollie. ‘The Founders of Australia’. This may be where Jane’s alias ‘Phillips’ came from

To avoid an excess of footnotes information may be found on the following:

https://peopleaustralia.anu.edu.au/biography/fitzgerald-jane-31019

https://www.freesettlerorfelon.com/searchaction.php

https://peopleaustralia.anu.edu.au/biography/dunnage-joseph-30792

https://www.freesettlerorfelon.com/lime_burning.htm

https://hmssirius.com.au/elizabeth-lock-convict-lady-penrhyn-1788 https://hmssirius.com.au/thomas-williams-private-marines-33rd-plymouth-company-friendship-1788-and-ann-lynch

https://hmssirius.com.au/elizabeth-lock-convict-lady-penrhyn-1788-and-thomas-scully by Cathy Dunn.

With thanks to the blog ‘Thornbury Roots’ which led me to James Cleaver.

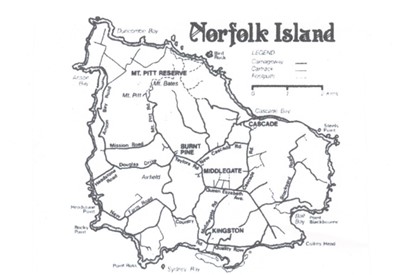

Norfolk Island: an explanation

Everybody has heard of Botany Bay but the settlement on remote Norfolk Island established in March 1788 is less well known, unless it is for the brutal penal colony that existed there from 1825 after the original convicts/settlers had long died, served their time or had been resettled in Tasmania. Norfolk is almost midway between Australia and New Zealand, and nearly a thousand miles from both. It was originally thought that its majestic tall pines would be useful as ships’ masts with the local flax plants for the sails. Though eventually neither proved suitable, the place was blessed with fertile soil and a temperate climate where agriculture was likely to flourish.

By the end of 1789 there was severe shortage of food at Sydney Cove despite the fact that this rich land had sustained Aboriginal communities for thousands of years. The situation grew worse when the Guardian, expected from Cape Town with provisions failed to arrive. Rations were drastically reduced. To avoid widespread starvation, a scheme was devised to reduce pressure at Sydney by sending part of the community to Norfolk Island where the Sirius would unload the passengers and continue on to Canton (now Guangzhou) in China, more than five thousand miles away, for supplies.

At 6 a.m. on 6 March 1790 Sirius accompanied by the small brig Supply set sail with 275 people on board, 116 male and 67 female convicts, 27 children and 65 marines, including Lt Ralph Clark, who was very sick, ‘I am poor soul at sea’ but still managed to keep up his daily Journal: ‘between decks there Such a disagreeable Smell from the women that are Sea Sick that it is a nuff to Suffocate one.’ He cheered up when a sow he had brought with him gave birth to six fine piglets.

On 13th March with a moderate wind and clear weather they ‘stood in’ for Norfolk Island’s Sydney Bay, but finding it unsuitable for landing, the ships sailed on to Cascade Bay where the first of the ships’ boats was lowered, loaded with male convicts and baggage and ferried ashore. When the boat landed safely another followed with the marine guards aboard, including Clark, who ‘got on Shore without getting my feet wett…..though I never landed in Such a Bad Place in my life’. When the third boat, carrying women neared land

‘a sea Brok into the boat which frightend them very much and I wonder the boat not lost with everybody in it for the women would not Sit Still but made a terrible noise, both them and ther children.’

With the tide too high round ‘the Rock’ for any more boats to land, Clark and the people on shore proceeded to make for ‘the town’, four or five miles away. Progress was slow. First they had to negotiate a hill ‘almost perpendicular’, and along a way so thickly wooded they could hardly get through it, with the convicts hampered by the amount of gear they had to carry. They had been on the go more than twenty four hours but instead of a warm welcome and the neat row of barracks Clark had been led to expect he grumpily observed ‘there is hardly enough room for those that is here before us.’

He bunked in with a surgeon’s mate, a Mr Jamison, ‘the detachment with those we found here and the convicts where they could.’

The next day when he encountered a party of convicts who, unable to get to town, had spent the night in the woods, he was in the mood to count his blessings,

‘Particular the women with young children…..poor Devils, they have been kick about from one place to another……’ He was not as a rule so sympathetic to women convicts.

Major Ross, the commanding officer, came ashore at Cascade the next day suffering badly with cramp, being so packed in a boat heaving with people, hammocks and livestock, (‘hoggs, geese, turkey, fouls’) that there was no room for his feet.

Over the next few days, the ships battled the fierce swell and attempted to return to the usual anchorage. They were out of sight until the 19th March when at about seven a.m. Supply came into view. As Sirius followed she came too close to the shore, and trying to turn away in a change of wind ‘struck upon a reef of coral rocks which lies parallel to the shore, and in a few strokes was bilged.’[1]

It was obvious she might soon break up. Clark

‘hoped to God they would be able to get some of the stores, otherwise saw no prospect ……except that of starving.’

Like everybody in the place he was soon trying to salvage the boxes, chests, whatever the crew of the Sirius managed to hurl overboard from the stricken ship some of which the sea brought to land. Captain John Hunter and 30 or 40 people came ashore on a grating, assisted by a hawser attached to one of the tall pines. A convict fell off a raft and pushed Clark into the sea with him. Clark swam to the shore with the other man who could not swim, clinging to the waistband of his trousers. Clark was livid.

‘When I got on Shor he was almost dead but he Soon Recoverd on which I took a stick ….and gave him a damd thrashing for pulling me of the Raft with him. He had better been drown for I will give him the Same every day for this month to come…..’

Jacob Nagle, an American sailor, was among those who remained on board Sirius all night under the spar deck, expecting

‘any minute she would go to pieces but her upper works was strong, as wood, iron, and copper bolts could make a ship fitted in England….’ Nagle and the rest were landed safely the next day.

Miraculously no human lives were lost during the disaster but much of the provisions and livestock remained on Sirius. Two convicts, Dring and Brannigan, swam out to the wreck with orders to throw the animals overboard in the hope they would get ashore alive. During their efforts they came upon the liquor store, and proceeded to get drunk. When they refused to return and the light of a torch was seen, it was feared they would set the wreck on fire. Another convict, John Ascott, volunteered to go aboard and sort things out. He insisted the two help him put out the fire, which was minor, after which they returned peaceably to land where they were put in irons. Ascott stayed the night on board in case the fire should spring to life again. Major Ross wrote, ‘how much we owe Ascott the carpenter…..but for his great and unparalleled exertions the Sirius and all her provisions would have been burned.’ Ascott was granted a pardon.

As for the animals, ‘the greatest part’ made land safely including Clark’s two sows, though all the piglets were dead, as were his fowls, apart from ‘my Cocks who Swam on Shore,’ but his chest was found empty with the bottom knocked out and his possessions including his spare clothes looted. His coat was afterwards washed up on the beach and a comrade loaned him half a dozen shirts as his own was ‘as black as the back of a chimney.’

The sailors, including Nagle, were ordered back on board to strip the broken Sirius of anything else of use they could find, ‘up to (our) neks in water by night and day and so we had no rest.’ He made two epic swims to and from the reef, having lost the toss of a coin for the honour, with a fellow sailor, William Hunter, to obtain orders from the captain, John Hunter (no relation). Captain Hunter said that ‘I had run a great risk to my life already.’

He and William Hunter were unusual among mariners in being able to swim, though there were a few others as Nagle says ‘we that could swim often went back to get copper off hur bottom to make kettles for all our pots was lost’ and five months later ‘we got hur guns out excepting one that fell overboard when first castaway.’[2]

When Supply ‘and some of our officers left for Sydney to inform the Govenor of our misfortune. (He) not knowing what time a fleet would arrive from England, sent (her) away to Batavia to take up a vessel and load it with rice for the coloney.’

The Norfolk Island community was now alone in the middle of the ocean with Major Ross in charge, who, said Nagle, was

‘a merciless commander to either free man or prisoner. He laid us under three different laws, for seamen still under naval law, the soldiers under millitary laws, beside the sivel laws and a marchal law of his own directions with strict orders to be attended for the smallest crime whatever or neglect of duty.’ [3]

Nagle estimated the population of the island, sailors, soldiers, officers and convicts numbered about 700 people.

Land clearance for farming and gardens was soon in full swing. Seeds, including potatoes salvaged from the stores had been sown. Though some were still beach combing, others were at the quarry gathering stones to build an oven. Nagle and the sailors were employed cutting down trees for the officers’ accommodation, though many of the men, he says, preferred to raise their own huts on the beach and each one had a woman with him.[4]

But the main pre-occupation was finding enough to eat. They fished with mixed success, mostly ‘snappers’ but caught an occasional ‘black cod’ and once a large turtle. Sometimes only half the convicts would get fish and the others had to hope for the following day’s catch. Another staple was the wild ‘mountain cabbage tree’, cut down with ‘the small tomehocks we had brought out for the natives’ which had been saved by Nagle and the sailors from the wreck. They even found ‘wild bonanoes’ which they hoped ‘would turn out well by cultivation.’

When they first landed, gannets, having no natural predators, Nagle says, ‘would come open mouthed at you, but destroying a good many, they left the island…… but the principle see bird that resorted and bread was called mount-piters or mutten birds.’

At dusk they would drop to the ground and look for their holes. The birds were

‘the chief living, the saving of us, as God would have it, as long as they lasted.’

From April onwards the margins of Clark’s Journal contain a tally of ‘Birds Kild’, some days even the total caught by various sections of the populace: ‘Marines, 398. Sailors, 594, Convicts, 1130.’ The bounty had to be shared among everybody with no private feasts allowed. Disobedience was punished in the usual manner, as on 12th May when Usher, a convict was given 50 lashes for the offence. Clark was disgusted that the convicts would go to the cliffs at Mount Pit, for the sake of birds’ eggs:

‘them that have no egg they let goe again and them with egg they cut the egg out and then let the Poor Bird fly again which is one of the Cruelest things which I ever herd,’

….this, from one who stood by with apparent equanimity when men were flogged, ‘300 on the bare back’.

Originally the birds were ‘thick as gnats’, but the total killed up to the 17 July 1790 exceeded 172,000. One imagines the women doing all the ‘plucking and drawing’ but this labour is not mentioned.

‘As long as they lasted’, Nagle, a natural ecologist, had realised the mutton birds were a finite resource. And of course they didn’t last. The birds became extinct.

‘The melancholy loss of HMS Sirius’ by courtesy of The National Library of Australia

On 7th August Nagle’s heart ‘leaped within me…… I hollowed out ‘Sail Ho! Sail ho!’

The ship was coming round the point in easy sail, and a short time later another sail ‘was in the offin.’ The ships were the Surprise and the Justinian. Although they were able provide welcome provisions and news, such as the sinking of the Guardian which had struck an iceberg, immediate rescue was not part of the package.

Aboard the Surprise were more convicts who had arrived on the latest transports to Botany Bay who had to be accommodated. They included two women from Bristol, Shuke Milledge and Elizabeth Sieney who knew each other and were destined to meet two more old friends from Newgate, John Wisehammer and Joseph Elliot…………

To be continued…….

[1] Captain John Hunter of Sirius.

[2] Few mariners were swimmers. Death by drowning (falling from the tops being a professional hazard) was thought preferable to dying of hypothermia alone in the sea as the ship sailed off in the distance.

[3]Nagle’s opinion of Ross was shared by almost everybody. It is even said that Governor Phillip sent him to Norfolk to get rid of him, though on the island Clark seems often to have dined or walked companionably with him and his son, ‘Little John’. The boy, a ‘Volunteer’, aged eight, had accompanied Ross on the First Fleet in 1787. The fictional Ross is generally cast as the main villain, (i.e. in ‘Our Country’s Good’).

[4] Neither Clark nor Nagle record any of their own romantic liaisons, though Clark had a daughter with a convict, Mary Branham, who had arrived with the Sirius in March 1790. The infant born on Norfolk Island 23 July 1791 was named Alicia in an apparent nod to Clark’s absent wife, Betsey Alicia. Nowt so strange as folks.

Notes & References

I have drawn heavily of the accounts of Ralph Clark, marine officer, and Jacob Nagle, American sailor, both of whom were on Norfolk Island at the time, both talented diarists but otherwise ordinary men in extraordinary circumstances. I have kept their original spelling.

The Journal & Letters of Lt. Ralph Clark 1787-92, (op cit.) & The Nagle Journal, 1775-1829. Ed. John C. Dann. The manuscript of Clark’s Journal was acquired by the Mitchell Library of Australia in 1914, and Nagle’s hand-written diary was bought by Mr Dann in the 1980s for $1,800 from a New York autograph dealer. As neither Clark nor Nagle left any known descendants the survival of these two accounts during the interim is not far short of a miracle.

See also ‘Mary Kennedy – Adventures on the First Fleet and Beyond’ on this blog, 22 May 2021. Mary. from Bristol, the wife of a marine, was also on Norfolk I. and survived the Sirius shipwreck. Unfortunately she only left us a few words in a hymn book.

http://www.environment.gov.au/shipwreck/public/wreck/wreck.do?key=7956

Leave a Comment