It is often the case that the very next day after you have committed something to print more information will come to light. So it is with the family of Harriet Bumford Darke.

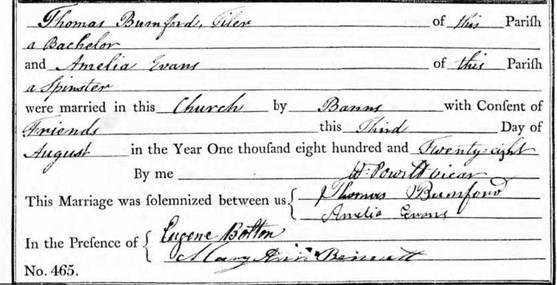

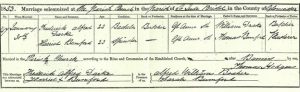

When I loaded the first chapter in Harriet’s story, I had only a record of the banns called when her parents, Thomas and Amelia were married – where the bride was incorrectly recorded as ’Elizabeth’. The registration of the marriage itself, which took place at St Mary’s, Abergavenny on 3rd August 1828 has now been found. Thomas Bumford worked as a “tiler” not a plasterer. His occupation ‘tiler’ has, unusually, been written on the top line with his mis-interpreted name – ‘Burnford’ – two reaspns why it has been missed by transcribers and indexers.[1]

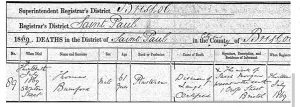

Thomas and Amelia had, as far as I can be sure, about ten children. The histories of Emma 1830-1, the tragic death of Thomas 1833-69:

and the sad lonely life of Edwin 1837-66 have been chronicled in the previous article, as has much of Harriet’s own saga, though there are now a few additions to her story.

Thomas and Amelia were fairly haphazard about having their children christened – no baptism has yet been found for Harriet herself, circa 1829 – and it seems that the custom died out completely after they arrived in Bristol. Of the remaining children, Joseph, born 1835 seems to be the only one who survived Harriet; his history is recounted at the end of this article.

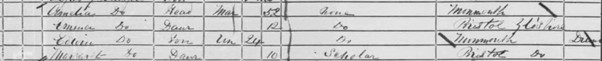

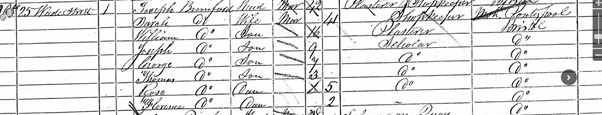

In 1841, when the census was taken on the 6th June, Amelia and her children were living at Jacob’s Wells.

George Albert is named on the census as “aged 3 weeks” which would suggest a birthday in the middle of May 1841. His life was destined to be cut short by small pox, aged three in 1844.Though the vaccine was becoming more acceptable, even if the Bumfords had approved, little George may have been considered too young to receive the dose.

Alfred Joseph who was baptised in Monmouth, was aged two when he is recorded by the census. Another bereavement followed in 1849 when he died of cholera on 11th June, during Bristol’s second outbreak of the epidemic. The family was then living at Redcross Lane, St Philip & St Jacob’s.

Alfred Joseph who was baptised in Monmouth, was aged two when he is recorded by the census. Another bereavement followed in 1849 when he died of cholera on 11th June, during Bristol’s second outbreak of the epidemic. The family was then living at Redcross Lane, St Philip & St Jacob’s.

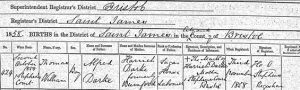

By 1851, the family had two more children had been born, two girls, Selina, then aged 7, born at St Paul’s, and Margaret, aged 2 months. The birth of Selina Emma was registered in Bristol in the December quarter of 1843. (Her rather fancy first name may have derived from a neighbour Selina Cutler who had lived next door to Amelia in 1841.) When the next population count came around in 1861, Amelia, her daughters Emma, “aged 12”, Margaret “aged 10” and Edwin, her son, shared premises at 20 Water Street, with Thomas, junior, his wife and family. There is no sign of “Selina” but the figure 12 next to Emma’s name is quite clear.

It seems unlikely that a 12 year old could have been mistaken for a 17 year old. I think though it is a mistake made in copying from rough notes. It is easy to mistake “2” for “7”. All the family members (plus those who put their research on Ancestry) seem convinced that “Selina died before 1861” and a child called “Emma” was born sometime between censuses 1851-61, though there is neither a death registration for Selina nor a birth registration for Emma. “Emma” who was not around in 1851, could not have been twelve years old in 1861. All this could be solved in a jiffy if anything at all could be found for one or all of them in any combination of names or in any variation of the surname Bumford. I feel that Selina Emma, Selina, and Emma are one and the same person, though the jury is still out on this one. All I can say is that by now, Selina or Emma, whoever she was (or they were) disappeared entirely from view after the sighting in 1861.

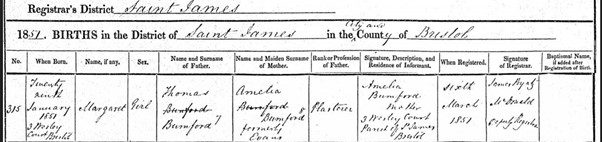

Margaret Bumford was born on the 29th January 1851, though her birth was not registered until 6th March. This confirms the census entry, that on 30th March 1851 she was almost exactly two months old. The address on the certificate is 3 Wesley Court, which is near enough the same as the Chapel Court in the parish of St James as stated in the census.

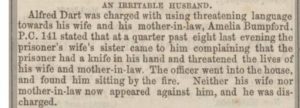

Nothing is known of Margaret for almost the first decade of her life. Then on 1st December 1860, Alfred Darke, Margaret’s brother-in-law, shows up in the local paper, the Western Daily Press. For this sequence we need to be reminded that Alfred was sometimes known as Frederick. The newspaper states his surname incorrectly as Dart, but there is no doubt in my mind that the charge refers to Harriet’s husband. Though the wife is not named, the mother-in-law is, Amelia, with her surname (also incorrectly spelt) as Bumpford.

Alfred was accused of threatening behaviour. The policeman concerned gave evidence that at a quarter past eight the previous evening “the prisoner’s wife’s sister” came to him and complained that Alfred, brandishing a knife, had threatened the lives of his wife and mother-in-law. When the Constable went to the house, he found the alleged assailant sitting casually by the fire. He seems not to have resisted arrest. True to form with this family, nobody appeared in court to corroborate the charges and the case was dismissed.

Alfred was accused of threatening behaviour. The policeman concerned gave evidence that at a quarter past eight the previous evening “the prisoner’s wife’s sister” came to him and complained that Alfred, brandishing a knife, had threatened the lives of his wife and mother-in-law. When the Constable went to the house, he found the alleged assailant sitting casually by the fire. He seems not to have resisted arrest. True to form with this family, nobody appeared in court to corroborate the charges and the case was dismissed.

So with the players in the cameo identified, Alfred Darke, his wife Harriet, and the mother-in-law Amelia, the question is, which of the wife’s sisters ran to fetch the policeman? Was it [Selina] Emma alive in whichever name she now favoured, or ten year old Margaret? I imagine it was the little girl, hoisting up her skirts to avoid the filthy mud and dung of the highway, scurrying pell-mell through the darkness of the November night – no street lights then – to fetch the Peeler….

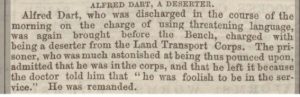

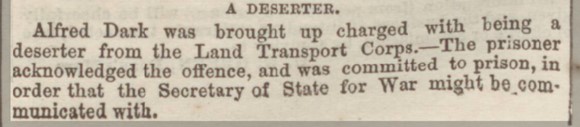

Though the case against Alfred for menacing his wife and her mother did not proceed, Alfred was re-arrested without before leaving the court. He was a wanted man, a deserter from the Land Transport Corps. Once again his name was spelt two ways, in the same newspaper. [1st & 3rd Dec 1860]

Though the case against Alfred for menacing his wife and her mother did not proceed, Alfred was re-arrested without before leaving the court. He was a wanted man, a deserter from the Land Transport Corps. Once again his name was spelt two ways, in the same newspaper. [1st & 3rd Dec 1860]

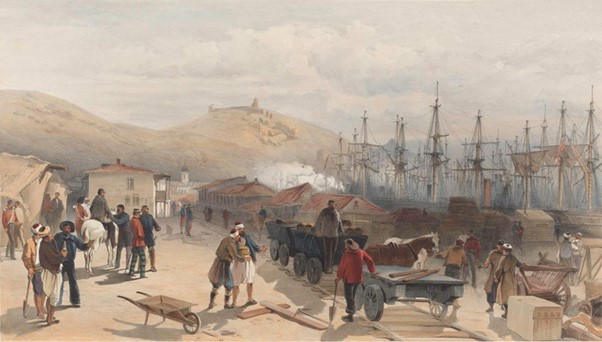

In the early stages of the Crimean War [1854-56] shortcomings in the supply chain for victualling and arming the troops caused public outrage which persuaded the Army to set up a special unit to deal with the problem. In 1855 this became the Land Transport Corps of which Alfred Darke was a sometime member.

In the early stages of the Crimean War [1854-56] shortcomings in the supply chain for victualling and arming the troops caused public outrage which persuaded the Army to set up a special unit to deal with the problem. In 1855 this became the Land Transport Corps of which Alfred Darke was a sometime member.

The Railway at Balaklava looking south (courtesy National Army Museum.)

There is no surviving record of his service [whether as Darke, Dark, Dart, Alfred, or Frederick] and neither has the Secretary of State’s opinion been reported. Military discipline was notoriously harsh and is unlikely Alfred went unpunished whether flogged or awarded a short prison sentence with hard labour. We know already that Alfred/Frederick was back within the bosom of his family by 7th April 1861, living at Penn Street, St Pauls.

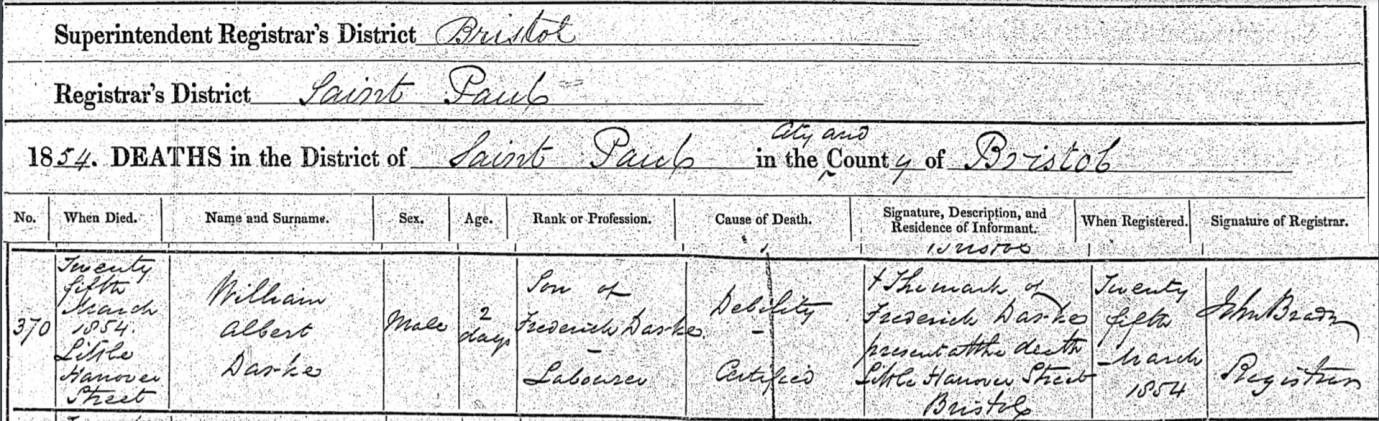

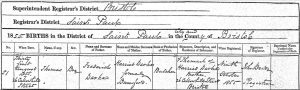

Alfred and Harriet were married in 1853. Harriet gave birth to William Albert on 23rd March 1854 at Little Hannover Street. This poor little scrap of humanity, ‘the son of Frederick Darke, labourer,’ died of ‘debility’’ aged two days on 25th March.

Alfred and Harriet were married in 1853. Harriet gave birth to William Albert on 23rd March 1854 at Little Hannover Street. This poor little scrap of humanity, ‘the son of Frederick Darke, labourer,’ died of ‘debility’’ aged two days on 25th March.

Frederick who had been present when the baby died made his mark when he registered the death – which is a separate mystery. He had managed to sign his name when he got married but on this occasion made ‘his mark’. Had he forgotten how to write?

A second son, Thomas, was born in August 1855.

A second son, Thomas, was born in August 1855.

The baby died at 26 Callowhill Street, aged 2 months, on 29th October 1855. He had suffered pneumonitis for the past 14 days. On this occasion the death was registered by Harriet’s sister-in-law Sarah Bumford which suggests the husband’s absence. The deaths of both boys were ‘certified’ by a doctor. How did they pay for a Doctor?

The baby died at 26 Callowhill Street, aged 2 months, on 29th October 1855. He had suffered pneumonitis for the past 14 days. On this occasion the death was registered by Harriet’s sister-in-law Sarah Bumford which suggests the husband’s absence. The deaths of both boys were ‘certified’ by a doctor. How did they pay for a Doctor?

A third son Thomas William was born 2 October 1858:

A third son Thomas William was born 2 October 1858:

Alfred/Frederick would have been present 9 months before each birth which just about gives him time to have enlisted and served during the short but brutal war. He may not even have travelled overseas to the Crimean Peninsula. The picture shows the climax of the LTC supply line.

As we know from Part 1, Amelia, Harriet’s mother died a few months after the latest court appearance in August 1861.

Alfred & Harriet’s next child, Joseph Henry, was registered in the first quarter of 1862 (January to March). If there was a honeymoon period after the fracas when Alfred returned to the bosom of his family, it did not last long.

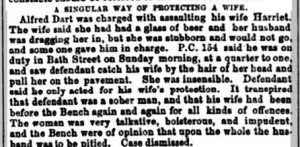

On 7th July 1863, again with the surname given as “Dart” Alfred and Harriet were in court again. Many Bristol people lose the last hard consonant of their words when speaking. Though Alfred was a Taunton man and Harriet originally from Wales, I wonder if they had picked up this idiosyncrasy and were saying their name as “Dar-“ with the last letter lost somewhere in the back of the throat behind the guttural roll of the famous “Bristol R”.

On 7th July 1863, again with the surname given as “Dart” Alfred and Harriet were in court again. Many Bristol people lose the last hard consonant of their words when speaking. Though Alfred was a Taunton man and Harriet originally from Wales, I wonder if they had picked up this idiosyncrasy and were saying their name as “Dar-“ with the last letter lost somewhere in the back of the throat behind the guttural roll of the famous “Bristol R”.

The report says it all. This was a violent marriage. It is noteworthy that the Bench sided with Alfred. They knew Harriet of old.

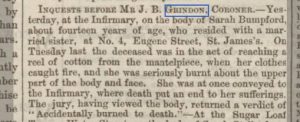

The next recorded tragedy to befall the family was on 15th March 1865. An inquest took place on the body of a child, Margaret Bumford aged 14 years. She was “accidentally burnt to death, her clothes taking fire”.

Two Bristol papers recorded the event,[2]and although they were completely wrong about the name, they were correct about the age. The reports differ in only one respect: the second says the girl was “of weak intellect”. They are otherwise similar enough either to be have been written up by the same person or two cub reporters who compared notes.

(“What was the girl’s name?”

“Dunno. I didn’t rightly hear it.”

“Let’s say Sarah. Nearly every girl’s a Sarah or Mary!”

“Toss you for it?”

“Sarah it is!”

“Coming down the pub?”

“Right-oh!”)

Reporting minor stories was never popular in the local newsroom – most of the youngsters sent on such errands regarded “down the Magistrates’” (where all human life in every version of banality resided) as a tedious ordeal. They really longed for a juicy murder and a transfer to Fleet Street among the big boys.[3]

Reporting minor stories was never popular in the local newsroom – most of the youngsters sent on such errands regarded “down the Magistrates’” (where all human life in every version of banality resided) as a tedious ordeal. They really longed for a juicy murder and a transfer to Fleet Street among the big boys.[3]

“Sarah” or Margaret was visiting her married sister – Harriet – and by reaching down some cotton from  the mantelpiece suffered horrific burns to her face and upper body. She was taken to Bristol Infirmary where she died of her injuries. Such accidents were frequent, usually involving children left to mind younger ones, or the elderly.

the mantelpiece suffered horrific burns to her face and upper body. She was taken to Bristol Infirmary where she died of her injuries. Such accidents were frequent, usually involving children left to mind younger ones, or the elderly.

If one imagines a dainty reel of cotton it was probably a much larger spool and possibly knocked her over. It is even possible it had come from the Great West Cotton Works. Margaret was of an age to have been working there in the factory where many local girls were employed.

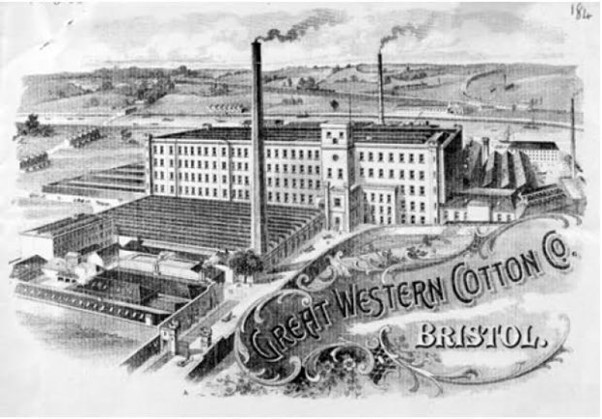

On 6th January 1866, Harriet’s last child, a daughter Amelia Emma was born. Yet another address, Eugene Street St James. , Alfred

As we already know, Harriet made a suicide attempt in 1867. In early March 1868 Harriet and Alfred made their next recorded public appearance described as,

“the most unhappy couple in Bristol”

Who

“monthly …… even fortnightly, were before the magistrates.” [4]

At this time Harriet must have been about two months pregnant with twins.

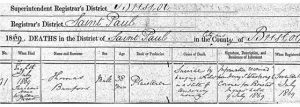

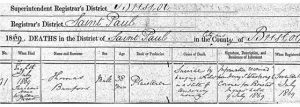

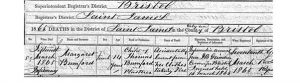

The baby twins died at six weeks old. Harriet had lost her babies and in the next year, 1869, both her brother, from suicide, and her father through disease of the lungs. Thomas must have been affected by the dust from the plaster with which he worked all his life:

By 1871 Harriet’s marriage was over. She and her husband had separated and he had taken up with another woman, Elizabeth. Notably, she made only one more appearance in the newspapers, (as Harriet Dart), called as a witness when a Sarah Cooper was charged with theft of clothes at a house in Penn Street where Harriet, said to be a relative, lived. Cooper was arrested in a pub in Water Street where she and Harriet had been drinking.[5]

By 1871 Harriet’s marriage was over. She and her husband had separated and he had taken up with another woman, Elizabeth. Notably, she made only one more appearance in the newspapers, (as Harriet Dart), called as a witness when a Sarah Cooper was charged with theft of clothes at a house in Penn Street where Harriet, said to be a relative, lived. Cooper was arrested in a pub in Water Street where she and Harriet had been drinking.[5]

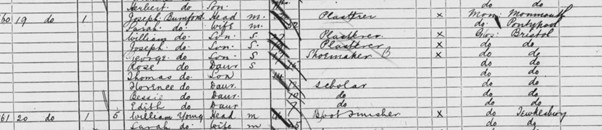

At this point enter Harriet’s remaining brother, Joseph Bumford, last seen in 1851, aged 16, a plasterer, like the rest of the Bumford males when residing with the family at 3 Chapel Court. He married his wife Sarah Jones at Pontypool in 1859 and in 1861 they were living at Charlotte Street, St Paul’s stated to be 24 and 22 respectively. In due course they had a little boy, William. From previous information Joseph seemed the exception within the Bumford family by leading a totally uneventful life. By 1871 he and Sarah seemed to have gone up in the world just a little. Though Joseph was still working as a plasterer, he was also the landlord of the Jolly Tanners at 59 Great George Street. William, their only child, was six years old. In the family group with Joseph and Sarah were Esther Dudfield, 14, a niece, a scholar from Monmouth, and seventeen year old Amelia Spencer, a living-in servant, perhaps a barmaid in the pub.

Matters appeared stable. Then it all began to unravel.

In July 1874 Joseph was summoned to appear in Court that “on the 8th June last he did feloniously steal, take and carry away £20, the moneys of John Bailey.” Bailey was a somewhat shady Bristol ‘businessman’, the owner of the Jolly Tanners. Joseph Bumford was his tenant who had been given notice to quit, but in the meantime had assigned the license to a man named Brittan, the price being £92. 10s. Certain deductions were to be made from the price, £10 to Mr Bailey and another £10 to Brittan to secure him as incoming tenant from any liability as to rents and taxes. This was to be handed to Mr Bailey to keep as bailee. The parties met on the 8th June in the pub when £72 10s was given to Bumford and the remaining £20 placed on the table. Bailey was reaching for his purse, when Bumford swept the £20 from the table, and shouted “I won’t part with a farthing of the money.”

After much deliberation, it was decided that the money was not stolen by Bumford as it was his own money and did not belong to Bailey in the first place.[6] It was a narrow squeak and Joseph left Court a free man. However, the Bench was apparently unaware that on the previous 19th April he had filed for bankruptcy.

In September, “lately the landlord of the Jolly Tanners” Joseph was on trial again, this time for fraud, “in that he did not disclose the whole of his assets to the trustees”. He was remanded on bail until the next sessions for learned Counsel to prepare their cases for the Prosecution and Defence.[7]

In October the case came to trial. Mr Poole, prosecuting, said this was a relatively simple case, only complicated by the fact that one of the principle witnesses was an accomplice to the offence. In late April, the defendant, Bumford, had petitioned to liquidate his affairs and on the 1st May made a statement verbally and in writing that his debts amounted to £294. 11s. 11d and his assets to £10. Out of the debts there was a preferential sum of £22 made up of £18 due for rent to the landlord, Mr Bailey, and the rest for rates and taxes. The defendant stated that the fixtures and fittings belonged to Bailey and he, Bumford owed him £40 on them. Mr Bailey was present and confirmed the statement. They produced an agreement that the goods and fittings were the landlord’s and Bumford had to pay £2 a week and £1 a week to clear off the debt. At the meeting of creditors he offered one shilling in the pound. This was not accepted and the defendant became bankrupt. The matter passed into the hands of a Trustee who received an offer of £95 for the goods and goodwill of the Jolly Tanners and he informed the defendant of the fact. Bumford then told him that the fixtures and fittings belonged to Mr Bailey who had a claim of £40 on them and detailed other claims which brought up the amount to £88 which must be paid before the creditors would get anything. The defendant made an offer to the Trustee to release the estate of the £88 and to give him £10 in addition, remarking that he “could do more with the business than anyone else.” The Trustee, believing this statement thought it would be the best for the estate and accepted the offer. The solicitor Mr J.B. Williams and the landlord agreed to release the estate for the £88 on it. Subsequently, the defendant sold the Jolly Tanners for £90 to a man named Brittan.

Afterwards, Bumford and Bailey fell out, possibly because Bailey did not receive the sum he believed was his due. In the course of the row, certain words were overheard by others who brought the matter to the ears of the Trustee. Consequently Bailey was examined by the bankruptcy tribunal where he stated that Bumford and Mr Williams prior to the first creditors’ meeting had begged him to make a statement that £18 was due for rent and that the defendant owed £40 for the fixtures etc which were his (Bailey’s) until the money was paid. He first refused but later consented to make a verbal statement confirming this was the case, but not on oath. The statement about the fixtures belonging to him and the £40 due on them was entirely false.

Bailey was then cross-examined by Mr Folkard for the defence. Bailey stated he had been “a soldier, a cabinet maker, a cow keeper, a beer retailer, a licensed victualler and he could hardly tell what”. (Laughter) Now he was nothing at all. (Roars of laughter) He was independent now and did not ask anybody for anything. He did not know he was liable to prosecution for perjury. What would they prosecute him for? For speaking the truth? (more laughter) He said the Trustee did not withdraw the distress under his instructions. He was asked to sign a piece of paper but refused. He told Mr Williams he would do anything to protect Bumford but denied making out a certificate saying the rent was £18 a year. Brittan was paying £28 per annum. He had charged Bumford with theft of £20 but the magistrates dismissed the case. Re-examined, he said the charge of £20 was for removing the fixtures and for damage to the property. He was told this was a civil rather than a criminal case. He had been served with a writ for making the charge.

Mr Folkard addressed the Jury saying it was many a day since he had seen a case conducted with such vigour as that of learned counsel Mr Poole. It was as if the defendant was accused of the most diabolical crime ever perpetuated. He contended that Mr Bailey was entirely uncorroborated. He denied his client was guilty of fraud or of committing any offence against the Bankruptcy Act.

The Jury deliberated for some time, and when they returned said they could not agree. Ten were for a guilty verdict, the other two for an acquittal. The Recorder sent them back out to reconsider. On their return they delivered a verdict. “Guilty”. The Prosecution recommended mercy but the Recorder said the charge was so serious that he must pass a sentence of twelve months hard labour.

Sarah Bumford who had attentively followed the proceedings collapsed “in a fit” when the sentence was announced. She was carried from the court by policemen. With unnecessary disdain and contempt, both newspapers called her “a woman, said to be the prisoner’s wife.” [8]

(The Bristol Directory of Historical Public Houses shows that a person called ‘Brittan’ was licensee of the Jolly Tanners in 1863 followed by a gap until 1879, when it was held by a ‘Mrs Sarah Ann Britten’. It would seem likely that Brittan and Britten were the same family as the Brittan named in the text as ‘paying £20 p.a.)

Joseph survived his harsh sentence and in 1881, at 25 Wade Street, St Philip’s was back with his family, ‘a plasterer and shopkeeper’, now aged ‘42’. In the decade between the censuses the ‘only child’ William, by now 16, and working – (of course!) as a plasterer, had been joined by three brothers and two sisters. Joseph, George, Thomas, Rose and Florence.

In 1891 they were at 19 Cowley Street. Three of the boys were working, the two eldest as plasterers but the other, George was a shoemaker.

How had he managed to break with the family trade?

They were still living at 19 Cowley Street in 1895 when Sarah, Joseph’s wife, registered Harriet’s death.

…………………………………………………..…………..to be continued.

[1] I can’t take the credit. I am grateful for the diligence of my cousin Dorothy Acford who found this for me.

[2] WDP, B.T & M. 17.3.1865.

[3] In the 1950s I worked for the now defunct Bristol Evening World, and confirm this at first hand.

[4] WDP 6.3.1868

[5] WDP 7.12.1871

[6] Ibid 23.7.1874

[7] WDP, B T & M ,29.9.1874.

[8] This is my condensed version of a case reported at great length in BT&M 26.10.1874 and B.Merc. 31.10.1874.

Leave a Comment