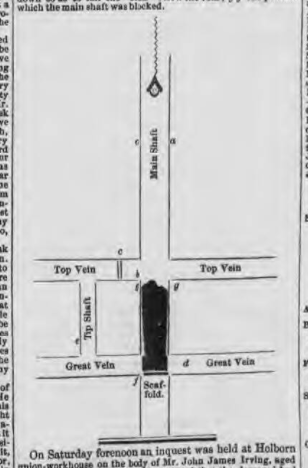

At 6 a.m. on Friday, the 20th June 1851, ‘a double turn’ (twice as many men as usual) descended Northside Pit, (Goulstone, Garrett & Co.) at Bedminster. The pit was 135 fathoms deep and the majority of the men were working at 90 fathoms below ground. Work proceeded without incident until 11 a.m. when a loaded cart which was descending the only shaft struck the side and in doing so, dislodged part of the timbers and earthwork. The entry and exit became totally blocked. Efforts to dislodge the debris and lower the cart began immediately, but progress was very slow and because of the precarious situation, only three men were able to work at one time.

At 6 a.m. on Friday, the 20th June 1851, ‘a double turn’ (twice as many men as usual) descended Northside Pit, (Goulstone, Garrett & Co.) at Bedminster. The pit was 135 fathoms deep and the majority of the men were working at 90 fathoms below ground. Work proceeded without incident until 11 a.m. when a loaded cart which was descending the only shaft struck the side and in doing so, dislodged part of the timbers and earthwork. The entry and exit became totally blocked. Efforts to dislodge the debris and lower the cart began immediately, but progress was very slow and because of the precarious situation, only three men were able to work at one time.

News of the accident and the plight of the men trapped below surged through the district and wives, children, mothers and other relatives flocked to the scene. By midnight there was a very large assembly of people anxious for news. One woman, carrying her infant daughter cried piteously saying her husband, father, son, brother and uncle were all in the pit.

Mr Goulstone, the proprietor, ‘whose efforts were of a most untiring character’ slightly raised the hopes of the crowd saying that most of the trapped men were working in other places in the pit, remote from the shaft, branching in different directions, with good roads leading away. Whilst it was feared that the earthwork had displaced the two air trunks which passed down the blocked shaft, he believed that water which ran into the lower level of the colliery would carry with it enough air to preserve life at least temporarily.

Matters continued in a state of ‘painful uncertainty’ until 9 a.m. the next morning, when Mr Knight, the proprietor of Ashton Vale Colliery, who had volunteered to go as far down the shaft as possible, brought the first concrete news. He had been able to make contact with a man, William Braine, who told him that he and another miner, a Welshman, Morgan Phillips, were together, both unhurt.

Braine, with stoical practicality, said

We want lights and something to eat.”

Despite their tiredness, those who had worked all night, set to again, lines were procured and 3 lbs of candles were sent down. However, they could not get to the tip, and failed to make anyone below hear them. Rescue work continued with load after load of timber being used to repair the side of the shaft, but it was thought despite this huge effort, this could not be finished in less than 3-4 days. Quantities of earth continued to fall, and Mr Rennolds junior, of Malago Pit urged that at least an attempt should be made to bring up the two men who were known to be alive. He provided a bonnet from his own works to be fastened to the ‘hawling drain’ and suggested that small buckets or nooses should be placed at either side where the men could sit with their legs suspended. It would be necessary however in the first instance that somebody would have to descend in the bonnet.

“Will no-one try to save them?” cried Mr Goulstone, whereupon a young miner, James North, stepped forward.

North said “I will.”

He entered the bucket and descended. Braine and Phillips were brought up safely amid cries “Noble North!” from the spectators, some of whom were moved to tears.

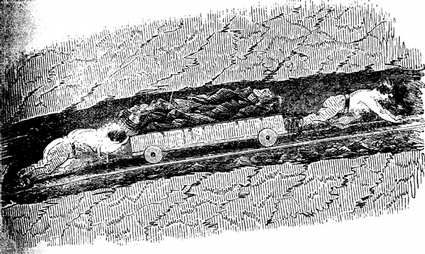

Weak and anxious, suffering from foul air, Morgan Phillips was pessimistic. He said he believed there was not a soul alive in the lower berth; that trying to keep a candle alight through the foul air would make all efforts futile. He said he had crawled on hands and knees to the tip, and repeatedly called, but not a sound could be heard. Braine was less despondent. He suggested a windlass should be taken down and fixed in the dark, so that some person might descend on a rope and grope for the missing men. North again gallantly offered himself for this task, joined by five others, Francis Smith, Samuel Page, William Smith, William Cooper and Richard Pike.

Francis Smith and Page went down first, carefully examining the shaft as they proceeded, and when they had reached the first vein the bucket was sent back for William Smith and Cooper. Finally North and Pike descended. A period of painful suspense ensued. Owing to the great depth to which the men were about to descend total silence had to be observed; their lives would depend on any signal they made being instantly obeyed by the engineer. At length the men returned ‘to the earth’, (that is above ground: miners spoke of ‘landing coal’ as if cargo from a sea voyage.) The air was foul, but they crawled through it, and believed it might be possible for men to survive something like ten hours. North said he crawled to the mouth of the tip where he “halloed” as loudly as possible and banged on a rock with his hammer for ten minutes but received no answer. He was afraid they might all be dead, but if not, he believed it was possible the air in the lower vein might be purer. The six men descended again shortly afterwards but were almost immediately driven back by the foul air.

Mr Goulstone determined that there should be no stone left unturned and when several more gallant attempts also proved ineffective, and with the bucket returned, Braine’s suggestion of a windlass was adopted. Canvas, and a strong rope 40 to 50 fathoms long, with a hatchet and other tools were requisitioned. It was decided to pump air into the pit through a large shaft made of the canvas via several hundreds of yards of air hose, to be obtained from the various fire offices in Bristol. (There was no centralised fire brigade at that time.) It was hoped this would give the poor fellows a chance of surviving should they be still alive.

‘The women and girls of the neighbourhood set to work and in one hour and a quarter had converted the canvas into an air trunk 80 fathoms in length.’

The canvas tube was passed down the shaft with a fan and a long hose supplied by the Imperial fire engine which had been cheerfully sent for the purpose. Mr Knight brought a ‘blow- charge’ from his own works at Ashton Vale to force fresh air into the upper vein rendering the tip approachable.

The apparatus produced an admirable effect and on descending again the rescuers found the air so much improved that they were able to approach the tip and burn their lights. A man named Boult with others was sent to the tip and managed to make contact with someone below, who conveyed the happy news that they were all alive. Food and lights were passed down. Page, a bailiff, thoroughly versed in colliery matters, now set to work and rigged up a wheel or windlass. A rope was lowered and James Pindar who had got into the tip shaft was raised up. By seven o’clock the last of the buried miners was rescued.

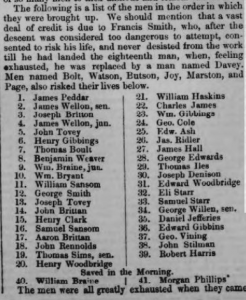

Francis Smith never ceased from his rescue attempts until he had delivered the eighteenth man, whereupon, exhausted, he was obliged to hand over to another called Davey. Other men who risked their lives were called Watson, Batson, Joy, Marston, and Kew.

A statement followed by ‘one of the most intelligent of the sufferers’:

“We were working, thinking of no danger when all of a sudden some of us felt a rush of air, which put out many of the lights and almost knocked us down. The boys went to the workings and called out that the pit had come together and begged the hands to come out and work for our lives. We were thirty nine in the bottom vein and two above. When we came to the shaft we were dismayed to find it filled up with earth, stones and timber. We could see no ‘lear’[space]. Some of us said “This is a bad job”, but Joseph Brittan the bailiff begged us to get to work as quick as we could to see if we could force a way to get air. A good deal of air came down with the stuff as it fell, but we could not tell how long it would last before it was gone. We worked to clear the stuff. We worked like men who worked for life. We worked so much we got out a great deal of earth and stones, that we filled a road for 70 or 80 yards or more. Then we found the timbers were standing athwart, above our heads and we put ropes around and all of us pulled and hauled to try and get them down. We got out a great deal more earth and broke a good many bars and a sight of stuff fell, but after working so hard, we found we not made much progress. We began to think we should never again see the light of heaven and that all would be smothered. Then one of us thought of another plan. Across the floor of the vein is a scaffold below which the shaft descends many fathoms towards a vein not yet reached. This scaffold is upheld by bars of wood. We thought if we could cut away these bars and let the scaffold fall, then the stuff would go down with it to the bottom of the shaft. [It was] dangerous work as the shaft side fell continually. We got up part of the coal house and with great labour sawed off the bars. Alas! We were doomed to another disappointment. The scaffold was jammed and we could not get it to fall. We were now very heavy-hearted and felt that the only chance left was to force our way up the tip-shaft into the top vein. We crawled through the air course for a quarter of a mile, our progress difficult, the course-way being very small. At one point the men had to be pushed and pulled through by the boys. During the Friday we got to the bottom of the tip and Peddar proposed we should push bars into the sides of the tip and make a kind of a ladder. Peddar drove one bar and then standing upon it, drove in another above, after which we passed him bar after bar which he drove into the side. The labour was very great and the time taken much, but it gave us hope of life and deliverance. The air grew worse and worse but he persisted. He had got up between 40 & 50 feet when the damp became so bad he could go no further.

Our hearts sank, but Joseph Brittan said ‘Now my men, we see that we can do do nothing more here. If we cannot move the bottom of the pit we are all dead men.’

So we returned to the bottom of the shaft, tapping it to let in air. Some men were cast down, others worked with desperation. It was our last chance of life. At about 3 o’clock on the Saturday a terrible calamity befel us us. The black damp rose so thick it put out all our lights and we were left in total darkness, and unable to do more, were impressed with the certainty of a horrible and fast approaching death. We all gave up hope of ever seeing the earth again and knelt down and prayed for the forgiveness of our sins. Daniel Jefferies, who was the only man who could do it, offered up a prayer to the Lord and we all joined in as well as only the poor and ignorant could and sang some hymns. Then we laid ourselves down to await death. Some of us were so worn out by labour and the agony of our minds, we fell off to sleep, but others kept praying and listening out for any sound that could give us hope. When we had awakened, Brittan begged us to go to the tip as Peddar thought he had heard something. We were afraid at first to go because of the black damp, but Brittan thought it had not got any worse and Thomas Boult, Henry Gibbings and Tovey volunteered, groping their way in the darkness. Boult knocked first and to his great joy heard a noise from the top vein. We could not believe the news of our deliverance at first, but when Tovey called and Henry Joy answered him, we were overcome with thankfulness to God who had wrought so great a dleiverance to us…….. We felt the blow-charge at work; the air came down and it was good, we sucked it in.Then the rope of the reel was put down and they pulled us up. So we got into the light of day which we thought would never shine on us again. Our hearts beat quick and our lips became parched, and we were overcome with gladness.”

Aftermath

Aftermath

‘The repair of the shaft is now being proceeded with but will take some considerable time. The pit will be unable to employ the rescued men but Ashton Vale Company which is on full operation will be able to supply partial employment for about forty of them.’

Notes

- This article is a digest of several very long pieces in Bristol Mercury 21 & 28 June 1851, and Bristol Times & Mirror, 21 June 1851.

- Anyone looking for ‘the Noble North’ in the 1851 census will not find him under that spelling. He is listed as James NEATH, a miner of coal, aged 21, born in Bedminster in 1830, living as a lodger at North Street, Bedminster, with Joseph Somerel, another miner and his wife Harriett. It would be interesting to know what became of him afterwards as I have failed to find him in later censuses.

- At the risk of labouring the point, I am so gratified that the heroic effort of the women and girls sewing the canvas for the chute was observed by the newspaper reporter. (Anyone who has ever tried to sew up a hole in a canvas tent will be aware of the difficulty.) This is the first time I have seen anything like this. Perhaps someone has another example. I am so used to seeing the women only noted for their sorrow, and being left destitute when their man meets with a fatal accident.

- For non-experts: Black damp is the suffocating mixture of carbon dioxide and other unbreathable gases that build up in mines and cause poisoning, asphyxiation and death.

- A fathom is six feet.

Acknowledgement

This article appeared in the newsletter of the South Gloucestershire Mines Research Group, no. 59, Autumn 2020, and is reproduced here by kind permission of the Editor.

Leave a Comment